The comic publisher ABO Comix faces unique obstacles: Its authors communicate by mail, but they’re prohibited from earning a meaningful income, so they struggle to afford postage, let alone art supplies. Also, government censors read every letter, sometimes refusing deliveries. Yet the Oakland publisher supports dozens of incarcerated queer and transgender artists nationwide, distributing collections of their autobiographical work to other LGBTQ prisoners.

Oakland's ABO Comix Publishes, Advocates for LGBTQ Prisoners

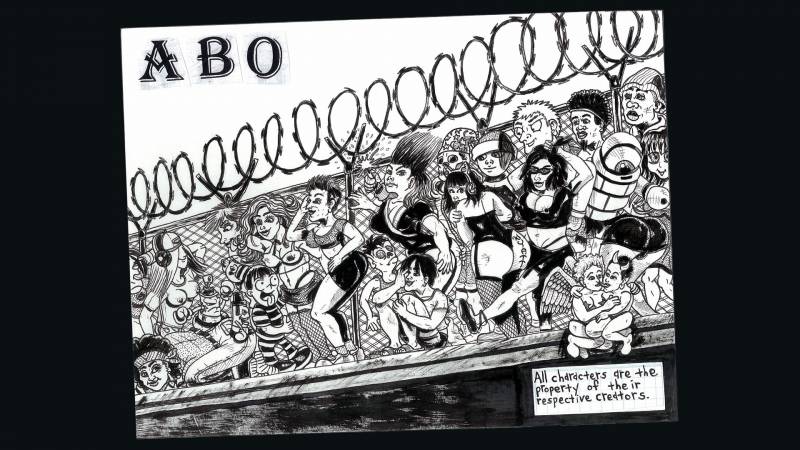

The perfect-bound collections are resources for and reflections of their primary audience: E.L. Tedana offers tips for the cell-bound illustrator, while Sirbrian Spease’s series Homo Thug’s Swagger explores queer cliques and relationships behind bars. Jamie Diaz stylishly deflects pejoratives for trans women while her swooshing coif provokes the ire of prison officials. One strip of Kinoko’s camp Mami Mamasita and the Booyah Girlz shows the prison yard as a stage, watchtowers shining spotlights, and H. Lee draws someone mailing themselves to a pen pal.

ABO’s existence is a reminder that LGBTQ people are incarcerated at twice the rate of the general population in the United States, according to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, and the comics describe the medical neglect, sexual predation and violence they often face inside. The latest collection is dedicated to Joseph Oguntodu, a contributor who was killed in prison weeks before his parole in March after complaining in letters to ABO about racist, homophobic bullying.

“I want the queer community to be united,” reads a quote from one of Oguntodu’s many letters to ABO beneath his smiling portrait. “I love each of you. Don’t forget to do something kind.”

Casper Cendre, 29, who moved to Oakland from San Diego in 2015, co-founded ABO Comix with Io Ascarium and Woof (who’ve both since stepped back from day-to-day operations). They launched the publisher with a call for submissions through the prison abolitionist organizations Black and Pink and Critical Resistance in 2017. “We thought it’d be a one-off collection,” Cendre recalled. “And then the P.O. box was just flooded.”

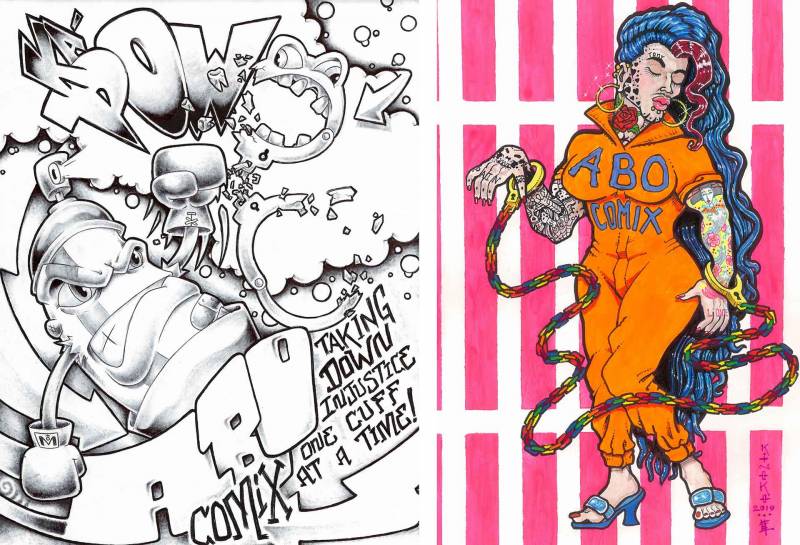

ABO has since paid incarcerated artists roughly $15,000 for contributions to standalone collections and three anthologies. The growing nonprofit, sponsored by the Queer Cultural Center, was recently awarded a California Arts Council grant to develop prison-based graphic-novel curriculum. It’s also received more than 1,200 pieces of mail from prisoners. On Saturday, Dec. 14, ABO celebrates the third anthology’s release at Classic Cars West with a set by punk band Anti-Repression Music, which collaborates with incarcerated writers.

ABO is part of a larger movement centering prison abolition, the belief that the prison-industrial complex must be dismantled instead of reformed, in the struggle for queer and transgender liberation in light of the way LGBTQ people are disproportionately policed and incarcerated. Black and Pink, one of the national organizations that inspired ABO, boasts more than 10,000 members “on the inside,” and describes its mission as to “abolish the criminal punishment system.”

Popular media such as Orange is the New Black have also buoyed trans prisoner visibility. Rachel Kushner set much of her abolition-inflected 2018 novel The Mars Room in a California women’s prison, and included a trans-masculine character named Conan. Early in the book, while discussing muscle cars, Conan passingly references how the prison system invalidates his gender identity. “If I was a dude I’d be like I am right now,” he says. “‘Cept not locked up.”

The movement is deeply rooted in the Bay Area: The Oakland-headquartered Critical Resistance popularized the phrase “prison-industrial complex,” and local writers Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith co-edited Captive Genders, an influential collection of essays on trans-embodiment and incarceration published by AK Press in 2015. One strategy these activists promote in order to mitigate state violence against LGBTQ prisoners is writing letters.

Many ABO artists are serving life sentences; often they’ve been incarcerated for decades, and their ties to outside kin are broken. “So mostly we form friendships, send birthday and holiday cards, or reference photos for their art,” Cendre said. “Basic human needs.” In prison, word of reliable pen pals travels, and ABO’s contributor clusters have spread from Texas and California to throughout the country.

Because ABO’s main audience is prisoners—it sends publications free upon request, and earns money when people buy them online on prisoners’ behalf—the publisher self-censors content, such as nudity, to accommodate prison guidelines. Yet facilities in states such as Kentucky and Nebraska still reject mailings for “inciting violence” or “overt sexuality”—examples, according to Cendre, of how prison administrators perceive any challenge to gender normativity as a threat.

ABO also plays the role of advocate. For example, when Cendre learned a pen pal suffered a stroke while isolation, through word from another prisoner, ABO volunteers inundated the facility with phone calls. (According to Black and Pink, queer prisoners are more likely to experience solitary confinement.) “Only then, days after the stroke, did he get any medical care,” Cendre said. Pressure from the outside, according to Cendre, can be more effective than from within because corrections officials tend to consider prisoner complaints illegitimate.

The publisher received more submissions for its first anthology than it could publish, but Cendre and other volunteers responded to every letter, often returning detailed feedback on the artwork. Sirbrian Spease, author of the Homo Thug’s Swagger strip, sent his first-ever drawings, and then dozens more over the course of a year. His crude outlines developed into intricate shading and perspective, and facial expressions subtle enough to convey the kind of joy found in hell.

ABO itself is often cast in the comic depictions of queer life in prison, referenced in speech bubbles and drawings of outgoing mail (or, in one strip, as the brand name of toiletries). Me and My Jelly Roll, Jamie Diaz’s contribution to the third anthology about her “extreme hairstyle,” seems to be written with the confidence that, through ABO Comix, the author’s grievance will reach the outside world: “I want people to know what is going on in here with girls like us.”