Recoding CripTech, a stand-out group exhibition on view at SOMArts through Feb. 25, reimagines what a body can be and do. Working with 11 artists and art collaboratives, curators Vanessa Chang and Lindsey D. Felt explore technology as a resource to be harnessed and hacked in service of ethical and wider social visibility for disability culture.

Among the themes that drive the exhibition, one is preeminent: disability is not a pathological state in need of correction. Realized with old and new technologies alike, the objects and discrete installations comprising Recoding CripTech do not demonstrate a desire to correct the range of challenges each maker lives with. Quite the opposite, in fact. These projects proudly assert disability as a cultural and political identity that demands recognition from non-disabled populations.

Language and its role in disability culture is addressed at the outset. “Crip” comes from the slur “cripple.” Like its cruel counterparts—“lame,” “deformed,” “crazy,” and the euphemistically condescending “differently-abled”—“cripple” denotes a cultural and linguistic power dynamic that marks difference as inferior or “other.” Much like “queer” was reappropriated by many in the LGBTQIA+ community, “crip” is used by many within disabled communities to indicate solidarity. From that contextual vantage point, the exhibition registers as a familial, collaborative effort.

Photographer Todd Edward Herman challenges us to think about looking. A meditative 15-minute video, Herman’s When I Stop Looking (2013) exposes a discomfiting reality: the desire to indulge spectatorial impulses by staring at his subjects, all of whom live with significant facial and cranial conditions. Herman’s reverent, moving work challenges us to consider how the gaze is activated in visually-oriented environments such as museums. What do we derive from looking? What do we extract from those we look at?

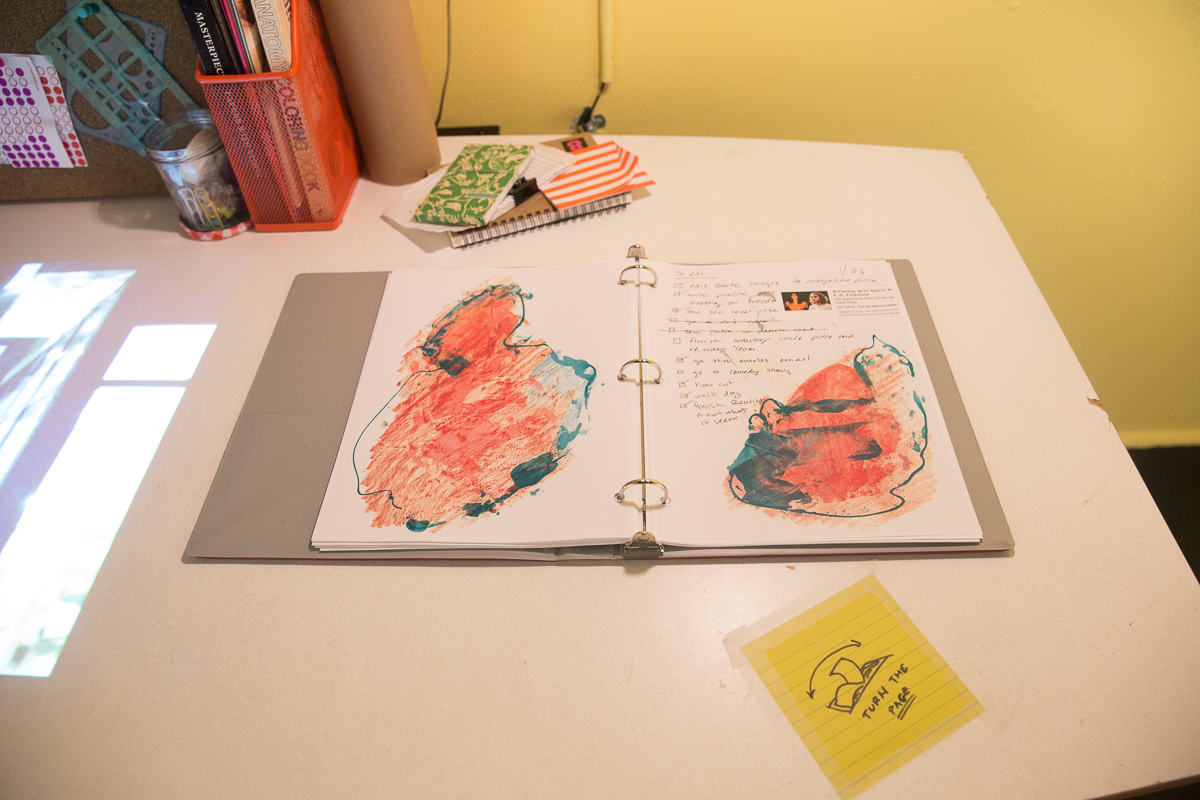

Recoding CripTech is replete with cutting-edge adaptive technology, including Prosthetic Memory, one of two featured projects by M Eifler a.k.a. BlinkPopShift and their collaborator Steve Sedlmayr. Set up to resemble the artist’s workspace, the installation includes custom-designed artificial intelligence (AI) that serves as a backup memory. Pages drawn from the artist’s daily written and video journaling practice, organized in a desktop binder, are read by custom software.