Patch O’Furr was running on five hours of sleep.

He’d stayed out late with his furry friends the night before. But Bernie Sanders’ campaign rally in Richmond was starting soon, so he and his squad woke up early and piled in the car. Since his purple-haired rat costume was still in the trunk, he put on the fur suit and scrawled “Furries 4 Bernie” in large block letters with Sharpie on a piece of cardboard.

As thousands of Sanders supporters lined up around the Craneway Pavilion to hear the senator’s speech on Feb. 17, people of all ages, including families with kids, stopped O’Furr every few feet for photos. Shahid Buttar, the democratic socialist running to unseat House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, posed for a picture and invited O’Furr to volunteer for his congressional campaign, noting that a giant rodent toting a slogan could have the impact of 50 regular volunteers.

“We’re here, we are furries, we are for Bernie, let’s do this,” says O’Furr, a 42-year-old Richmond artist and e-commerce entrepreneur who runs the furry news blog Dogpatch Press. “We’re not an organization, we’re just doing what we love.”

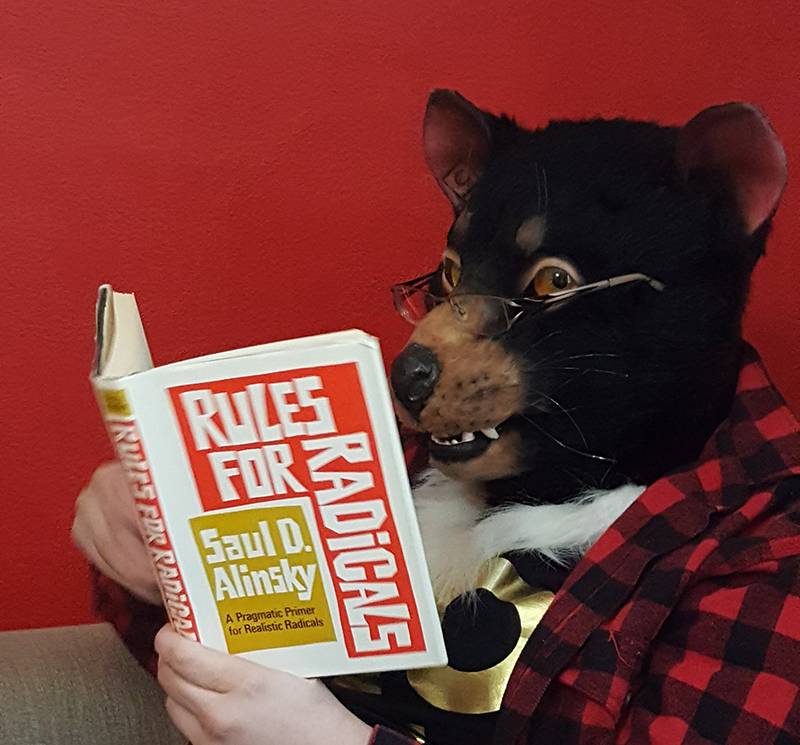

O’Furr is part of niche yet enthusiastic subculture centered around a love for anthropomorphic animal characters. Furries attend conventions and gatherings, make and commission artwork of their alter egos (or “fursonas”), chat with fellow enthusiasts online and dress up in fur suits that represent their animal identities. (The subculture has a reputation for being a sexual kink, but the furries I spoke with for this story say that aspect is overly sensationalized in the media and doesn’t represent the entire fandom.)

This election season, furries are entering the political arena in growing numbers. And while they might seem like an unlikely constituency to rally support for candidates, the fandom’s outsider outlook and robust social networks—both on and offline—make it particularly poised to mobilize for the progressive left ahead of the Democratic primary in California and nationwide.

A Subculture Ready to Get the Vote Out

Typically, furries find one another on Twitter and the chat platform Telegram, and meet in person at conventions like San Jose’s Further Confusion (FurCon), Midwest FurFest and Anthrocon, and dance parties like DJ NeonBunny’s monthly Frolic party at the Eagle in San Francisco. For many, the community is a chosen family that welcomes those who may feel socially ostracized. The fandom doesn’t revolve around a specific commercial entity, in contrast to subcultures that form around anime, video games or Star Wars. Instead, furry culture, much like the punk scene, emphasizes do-it-yourself participation and person-to-person connections. In essence, the people who make up the subculture invent it in real time.

“We’ve always been a deep-seated community of people who need somewhere to go, somewhere to find a universal love,” says Berry Pecan Tart, a 33-year-old barista from Napa who came out “of the cage” as a furry this year (his fursona is a California black bear). It was a moment of self-actualization that coincided with his joining the Democratic Socialists of America. With the DSA, he recently volunteered to fix car headlights to help undocumented immigrants avoid traffic stops that leave them vulnerable to deportation.

With many LGBTQ+ and neurodiverse people among their ranks, furries largely embrace progressive causes. “I know many furries doing phone banking, primarily in favor of Bernie Sanders—overwhelmingly, I would say—in Iowa and New Hampshire,” says Kamunt Kurush, a 29-year-old student and furry in the Chicago area who uses his Twitter platform to live tweet the Democratic debates and promote left-wing candidates (his fursona is a cheetah). Recently, Buttar’s campaign noticed Kurush’s enthusiastic posts and invited him to a private direct message group of people promoting the candidate’s pro-Medicare for All, pro-Green New Deal message.

“I knew somebody who even went to New Hampshire to knock on doors [for Sanders],” Kurush says of the furry community’s dedication. “A friend of mine who lives in San Francisco has volunteered for Shahid Buttar’s campaign to do some canvassing.”

In a previous generation, a politician running for congress might not have wanted to be affiliated with a subculture widely seen as fringe. But Buttar embraces the furry vote. “My recognition of the value of furries, my recognition of the value of subcultures generally is rooted in my own identity as an artist,” says Buttar, adding that countercultural groups have pushed progressive political ideas into the mainstream throughout history. “It’s not just furries—anyone who’s willing to raise their voice and be creative, artists, are the lifeblood of our community and our culture writ large.”