One of the most notable things in Elizabeth’s letters was her ability to always find beauty, even in the midst of war and destruction. One, dated July 23, 1917, states: “Just how much I can tell you of yesterday’s attack, I don’t know, but we tumbled out at 7am, clad hastily… The firing lasted about thirty minutes. The shots went all over and around us, but except for a few broken windows, no damage was done.” Just two sentences later, she writes: “The coast is very lovely. With glasses we can see quaint houses and we smell the new mown hay.”

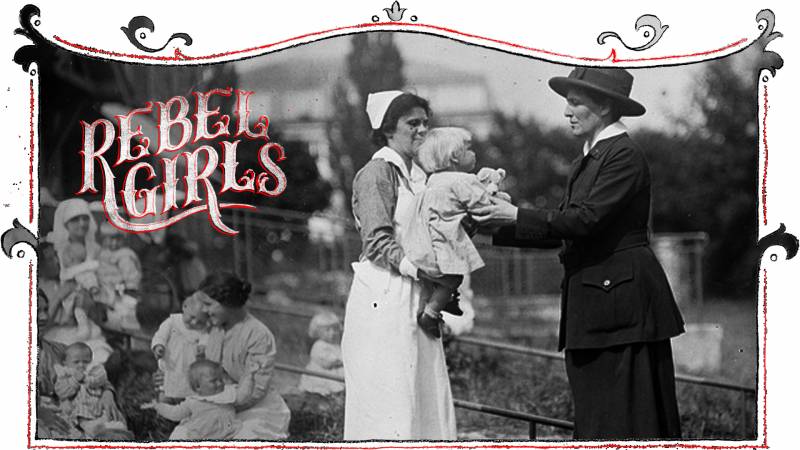

On her return to San Francisco in July 1919, Elizabeth went back to work at Hill Farm—also known as the Bothin Convalescent Home for women and children—that she had established in 1903, and then expanded in 1910 with the help of steel magnate and philanthropist, Henry E. Bothin.

Remarkably, just one year later in 1911, alongside Alice Griffith, Elizabeth also opened the Arequipa Sanitarium for tuberculosis patients. The facility, designed by San Francisco doctor Philip King Brown and prestigious architectural firm Bakewell and Brown, was established after Elizabeth and Alice managed to raise $20,000 from wealthy donors.

For decades, Arequipa had a long waiting list for admission, due in part to its state-of-the-art facilities and low costs for patients. However, as demand for its services dropped over the years due to medical advancements in the fight against TB, Elizabeth found new ways to use the space. In 1948, she gave a building to the San Francisco Girl Scouts for troop camping and, by 1959, the organization had taken over the entire property and added a swimming pool. The center was officially renamed the Henry E. Bothin Youth Center in 1963, and Camp Bothin—which offers programs for kids of all ages—continues to operate there to this day.

Elizabeth Ashe died in 1954, but her legacy of community service remains scattered across San Francisco and the North Bay, with the continued existence of organizations she worked tirelessly to establish. There can be no doubt that this most generous woman would be thrilled to see the longterm impact she made.

In one letter dated Sunday July 22, 1917, Elizabeth—known to her closest friends as Betty—humbly wrote:

Did I tell you that Miss Maxwell, in introducing me to a group of nurses, told them that I had humanized her training school, had showed them that all nurses did not have to be made after the same pattern?

I felt that I had not lived in vain.