At this year’s Grammy Awards (which, believe it or not, were only a couple months—and not decades—ago), YG, Roddy Rich, DJ Khaled, Meek Mill and John Legend paid homage to late icons Nipsey Hussle and Kobe Bryant in an uplifting choral performance in front of 18.7 million viewers. At various points throughout the segment, red and blue lights flooded the stage—an homage to YG’s Blood and Hussle’s Crip affiliations, both referenced proudly in their chart-topping songs.

How did Los Angeles gang culture, springing from the particular conditions of a city’s marginalization and violence, become such a defining feature of American pop culture and music? That’s a question San Francisco State University professor and historian Felicia Angeja Viator seeks to answer in her new book, To Live and Defy in L.A.: How Gangsta Rap Changed America, out now through Harvard University Press.

Rather than tell the stories behind Tupac and Snoop Dogg’s biggest hits, Viator takes a sociological approach, zeroing in on how economic devastation and militarized policing bred a subgenre whose extreme lyrics were fueled by indigence. In the late ’80s, the period the book spends the most time on, the earliest gangster rap was made for and by black youth who were vilified by the media, government and elders in their own communities.

“These kids who were making music in the ’80s, and may not be active in the gangs but are affiliated because they go to school with gang members, they live in neighborhoods with gang members, they’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. You’re compelled to socialize with gang culture, and then you’re demonized for it,” she says. “So you’re kind of doubly marginalized: you’re marginalized by outside society that sees you as a criminal, and you’re also marginalized within your own community.”

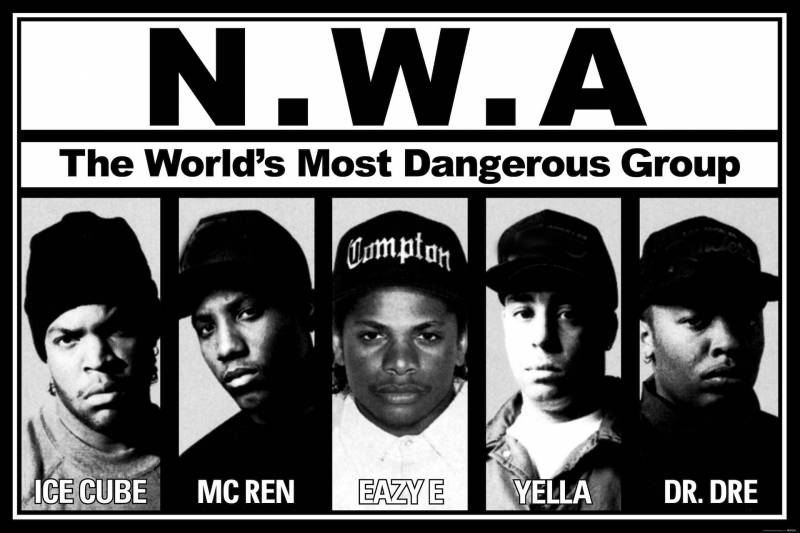

To Live and Defy in L.A. explores how L.A.’s teen gangs became a media boogeyman, and how civil unrest during the 1992 Rodney King riots broadcasted black L.A.’s frustrations with police brutality and poverty to the rest of the country. Conditions became ripe for America to tune into what Los Angeles’ street poets had to say. Artists like Eazy-E, Ice Cube and Dr. Dre tapped into a longstanding fascination with L.A.’s criminal underbelly with PR cunning and business savvy, and gangster rap became an enormous commercial phenomenon.