Harvey Milk quit the chronic when he got serious about politics, but his right-hand activist wrangler Cleve Jones continued as an occasional cannabis brownie consumer, scoring directly from the counter of his unofficial office at the Castro’s Village Deli. We know this because the daughter of his deli’s pastry dealer wrote a book: Alia Volz’s Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco.

Canna-history buffs will thrill to Volz’s retelling of wonky marijuana industry secrets, but ultimately she wrote Home Baked because of all you can divine about a society’s inner workings via its drug of choice. The early ’70s to late ’90s was a key period in San Francisco’s counterculture history, and had lasting effects on the state’s economy and public policy. That story is traceable through its green veins in Home Baked’s insider account.

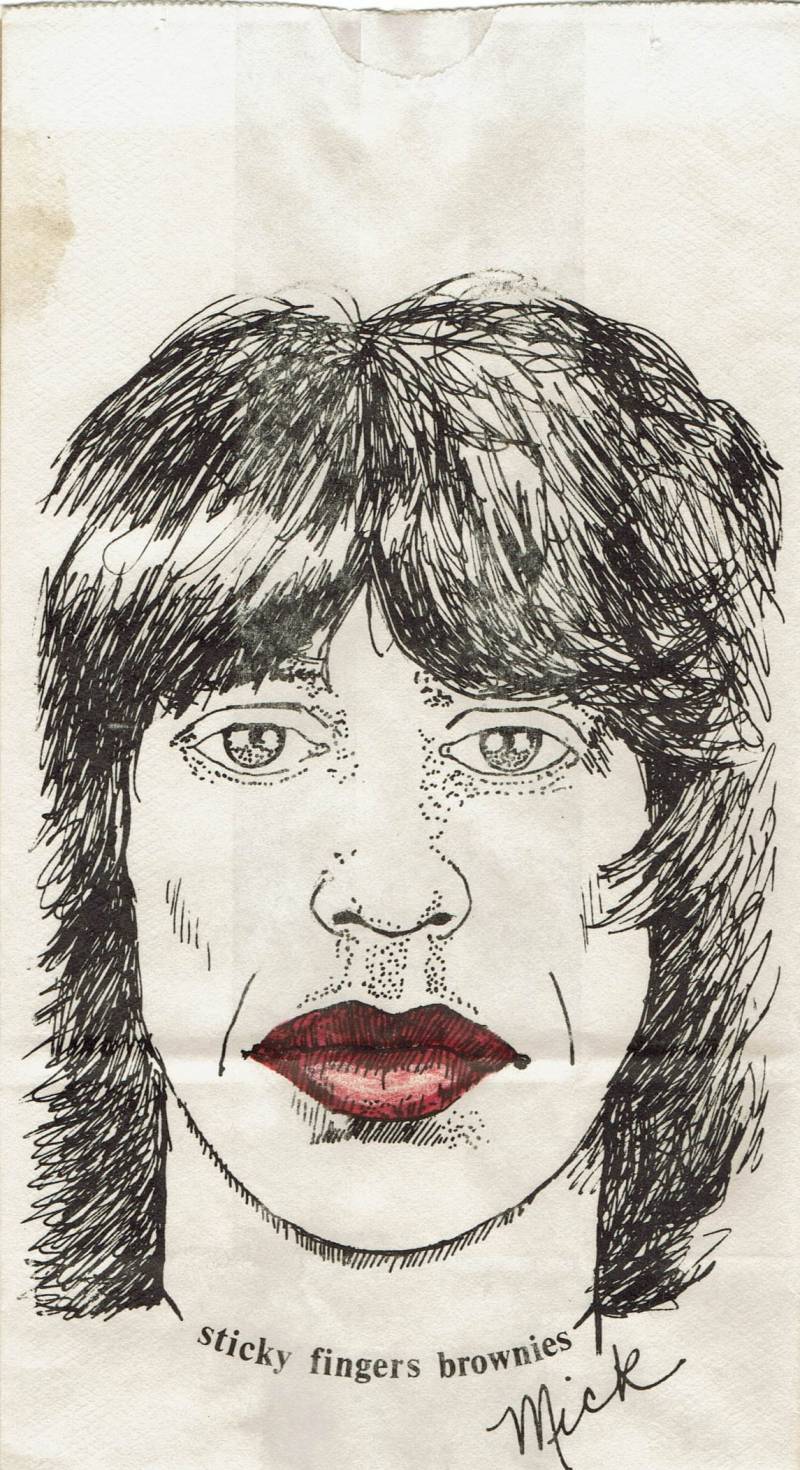

Volz conducted around 55 interviews over the course of hundreds of hours throughout the research process, most of them co-workers and clients of the book’s protagonist, Meridy Volz a.k.a. the Brownie Lady, co-creator of iconic S.F. edibles brand Sticky Fingers Brownies. Some big names show up on this list, including Jones, whose interviews with Volz provide incisive commentary on the era’s potent queer activism.

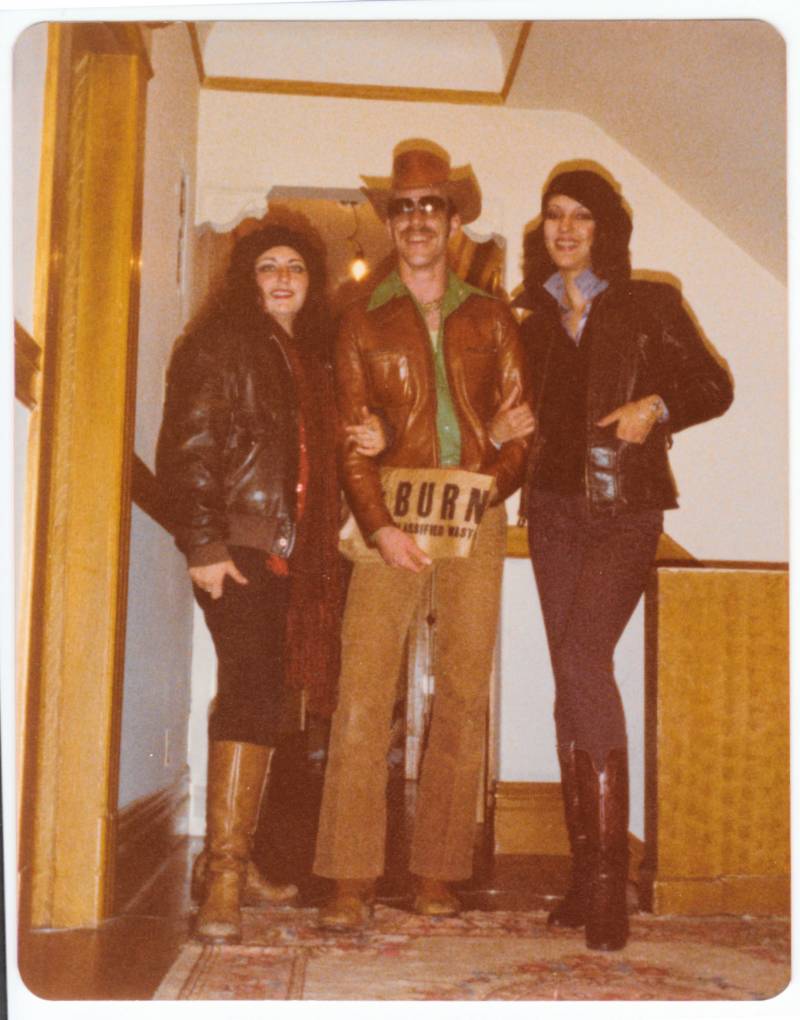

Though tumultuous family history often takes the foreground in Home Baked, Alia knew all along that what she really wanted to share was the story of how their popular pot brownies were linked with the jubilation of the 1970s gay liberation movement and the harsh comedown the city experienced after the Jonestown tragedy, assassinations of Milk and Mayor George Moscone, and eventual decent into HIV/AIDS. Throughout, cannabis powered the era’s artists and activists, and provided comfort during its horrific plague.

“I really wanted to tell the story of the community,” Volz said in an interview with KQED. “I eventually realized that in order to tell the social history that I wanted to tell, I had to smuggle it within a personal narrative. People really need that first person guide into the world to hold it together.”

The book’s narrative is studded with historical asides, and Volz’s engaging voice and insight on Sticky Fingers’ modus operandi makes it a quick read. The brand largely operated via vending bulk orders to counterculture businesses that would later resell the treats. A particularly detailed account of Meridy’s 1970s Castro sales route reads like a who’s who of local enterprise at the time, beginning at a variety and antique store called Hot Flash of America and proceeding to Café Flore, Finnila’s Finnish Baths, the Castro Theatre, Village Deli, the porn offices of Falcon Studios, a restaurant called Neon Chicken and Double Rainbow Ice Cream.