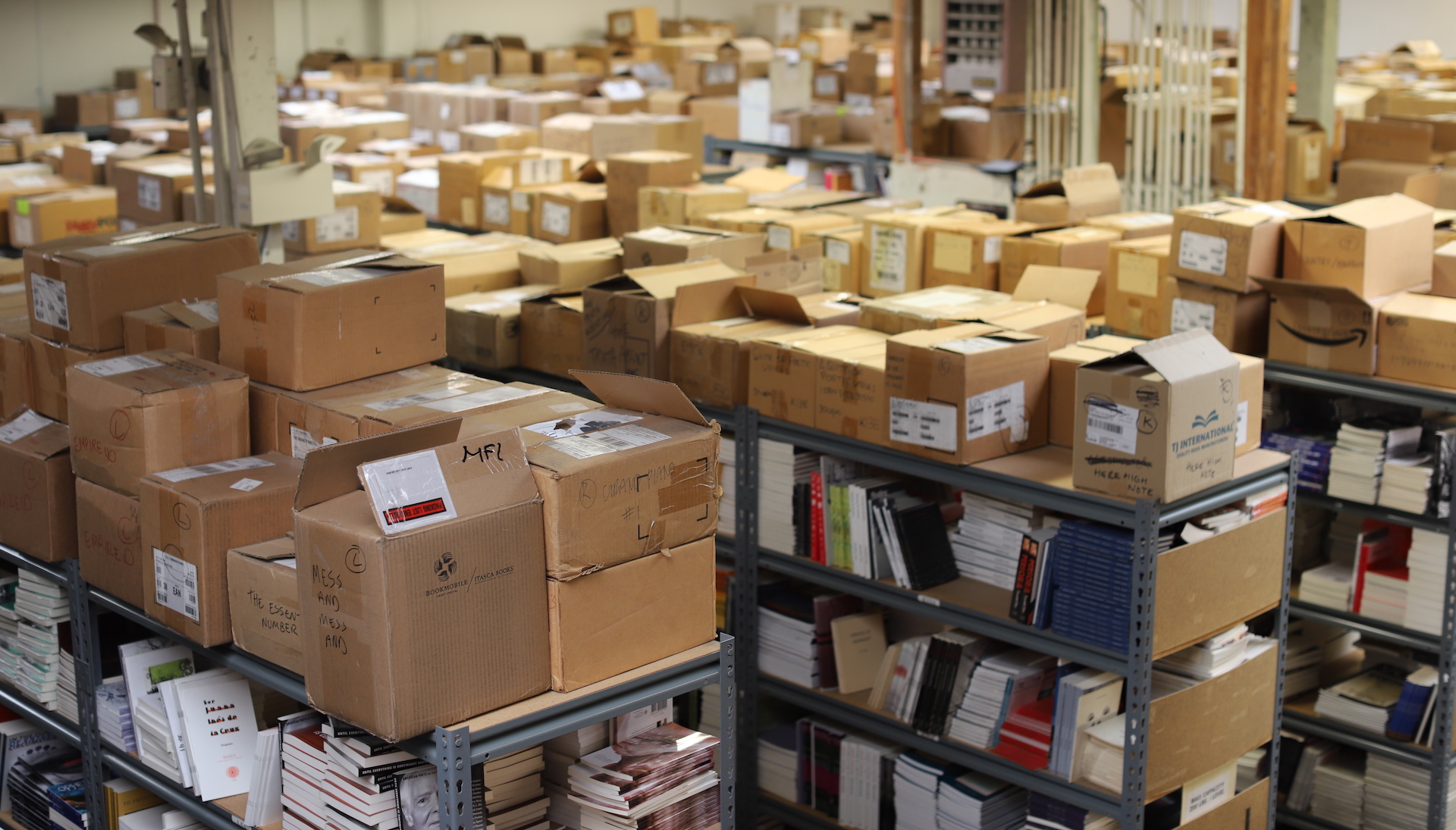

Liam Curley, warehouse manager at Small Press Distribution (SPD), the nation’s only nonprofit literary distributor, has for the past seven weeks worked by himself. Shipments to and from the 6,400-square-foot warehouse in Berkeley have slowed to a steady trickle. One morning recently, he parked his sedan on 7th Street. The bumper sticker says, “Driver carries no cash, they’re a poet.” He wore purple latex gloves and an N95 respirator, and walked through the dark office and kitchen towards the rows of some 350,000 books from independent publishers. The mask, Curley said, was actually a leftover from the last wildfire season. “The warehouse is very porous.”

Curley, 30, nodded to a cluttered desk with a computer monitor still alight, as if it had been abandoned in a hurry. “Everyone else is remote,” he said. “But you can see the ghost in the machine.” He could’ve been talking about himself: Curley plays a critical but little-seen role in the literary supply chain, especially for shut-in readers reluctant to buy on Amazon. (Curley alternates days with an assistant, Shawn El.) With bookstores closed, SPD’s revenue is down 60 percent, but he still packs more than a hundred orders daily, mainly for Amazon and direct sales. In the kitchen, a copy of the latest Publishers Weekly declared, “Books are essential.” Curley has doubts. “Books aren’t saving lives,” he said. “But it’s really about standing together as an industry.”

SPD, founded in Berkeley in 1969, has weathered decades of industry consolidation to persevere as one of few distributors still committed to small publishers. It markets and distributes titles from some 400 presses, selling to independent and college bookshops, wholesalers such as Ingram, online retailers including Amazon and individuals through its own site. As a nonprofit, it also receives key grant funding. In the past 20 years, SPD has actually grown. Last year, it moved four times as many books as it did in 1999. Now, the distributor is crowdfunding to cover payroll and health insurance for 10 employees. And readers, eager to support independent literature from home, are rallying like never before to support a business with little profile outside of its industry.

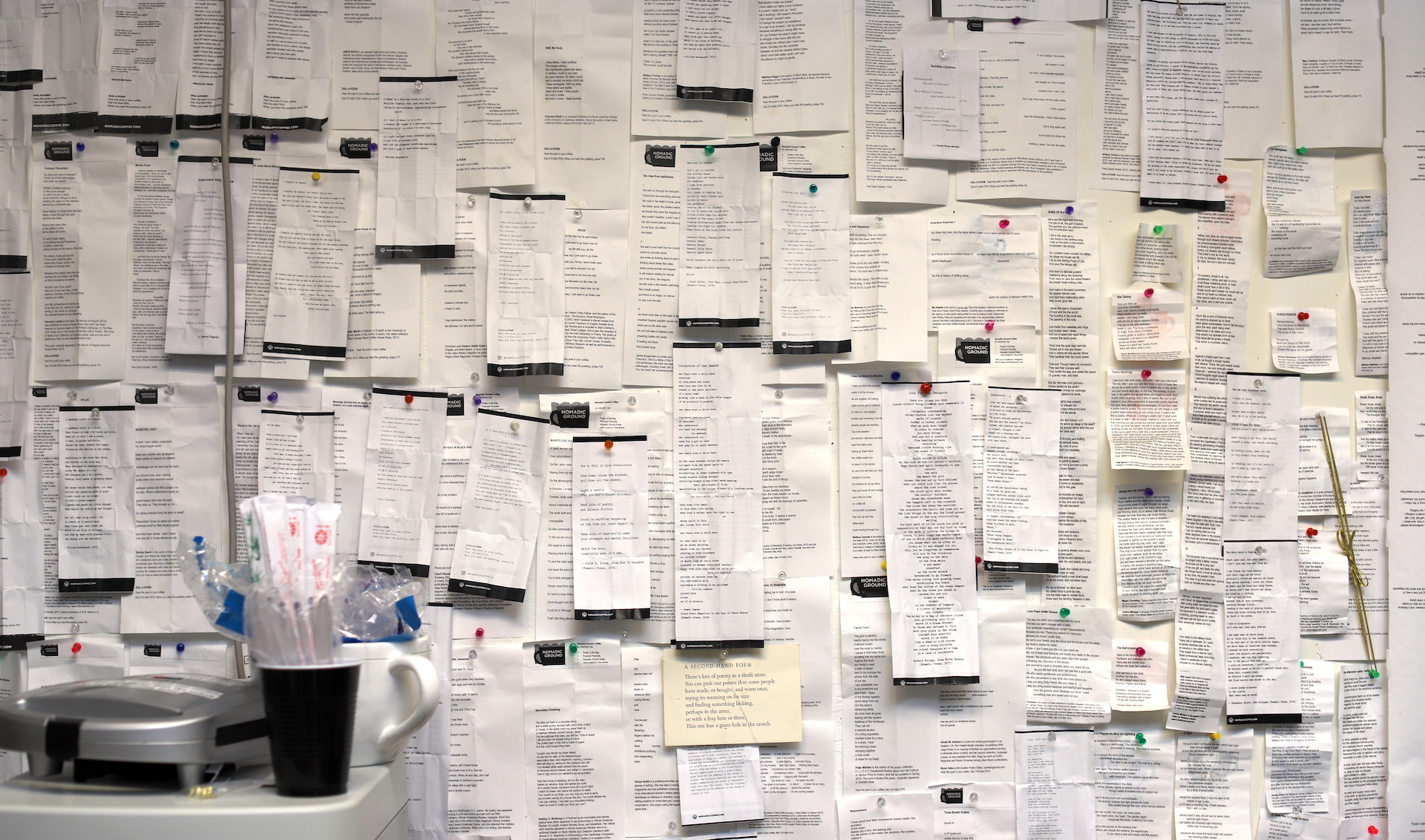

“We’re a part of the literary infrastructure,” Brent Cunningham, SPD’s executive director and an author—most recently of poetry chapbook The Sad Songs of Hell (Ugly Duckling)—said in a video interview. “You’ve got to know the art form and its economy pretty well to realize we even exist.”

SPD does not carry anything from the “Big Five” publishers or their imprints. It is an institution outside of the literary mainstream, with close community ties. “You can imagine most of the books we stocked early on were like this,” Curley said, retrieving a copy of Barbara Baracks’ No Sleep, a 1977 stapled chapbook published by Bay Area language poet Lyn Hejinian’s Tuumba Press. He started volunteering eight years ago when he moved to the East Bay on the recommendation of a former writing professor, Catherine Taylor of Essay Press. In the warehouse, he was listening to KALX; the DJ played a soul record at the wrong speed. “I can never tell if that’s on purpose,” he said. Curley noted local writers often deliver copies. Most recently, the writer and visual artist Linda Norton came to restock her experimental memoir, Wite Out (Hanging Loose Press).