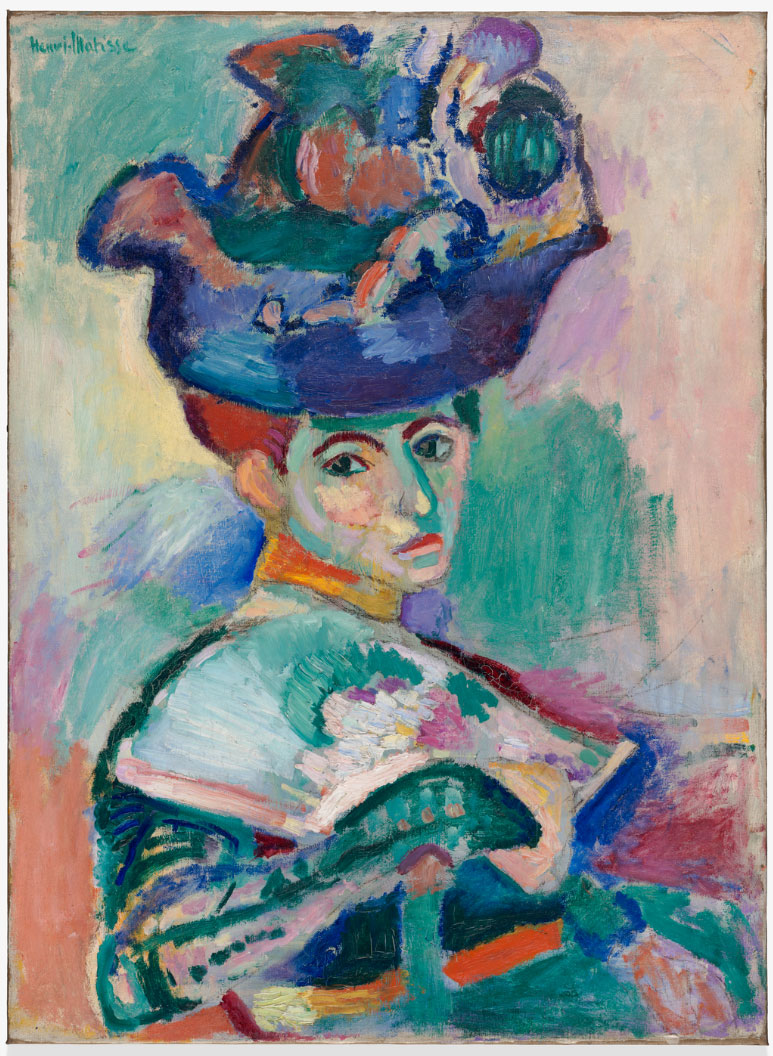

A few years ago, one of my best friends and I attempted to do a 1,000-piece jigsaw together. I bought a puzzle version of Henri Matisse’s Femme au Chapeau from the SFMOMA store and the two of us began working on it during Nicole’s regular visits to my apartment. It was my first adult attempt at a jigsaw.

What became apparent fairly quickly was that Nicole—a calm and gentle human—had the appropriate disposition for completing the Femme, while I—infuriatingly impatient—definitely did not. When Nicole came over, I didn’t want to sit and do a puzzle, I wanted to go to a bar, or a restaurant, or a movie. After investing about six hours in the jigsaw, and realizing it was going to take at least six more, I unceremoniously quit.

The Femme languished, half-finished, hidden under a table cloth on my dining table for the better part of a year, until Nicole finally gave up on me. When she arrived one day with a roll-up puzzle mat and whisked it away to finally complete the thing, I couldn’t have been happier to see the end of that project.

Fast forward to 2020, shelter-in-place day 60-something, and I have completed three 500-piece jigsaw puzzles in the last week. I finished three others in the month before that. And there are rules. If I start one on my own, my boyfriend is forbidden from helping me finish it. If we start one together, we generously take turns letting each other place the last piece.

Our obsession is now so full-blown, we braved a San Leandro Walmart last Saturday night in the desperate hunt for a new jigsaw. We found the shelves so woefully empty it was as if we were in the toilet paper aisle. (I eventually managed to find one solitary jigsaw hiding among the board games; we snapped it up.)