A few months ago, I felt like 2020 was going to be a pivotal point for mainstream cultural acceptance for the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. 2019 seemed to offer one win after another: Rapper Saweetie’s “My Type” became a summer hit; K-pop group BLACKPINK headlined Coachella; indie favorites Beabadoobee and Peggy Gou made big waves in the underground. Photographer Andrew Kung and Banana Mag brought Asian American identity to the forefront. And Always Be My Maybe, starring Ali Wong and Randall Park, won hearts with its Asian American take on a relatable rom-com plot line.

In the fall, the momentum reached a near-fever pitch when Lulu Wang’s The Farewell, a film that tells the poignant story of a Chinese-American family navigating their grandma’s cancer diagnosis, released to critical acclaim. And then there was Bong Joon-ho’s phenomenal Parasite. The film is actually a foreign one—it was created by a Korean filmmaker in Korea—but for me, it felt like a win when it became the first non-English film to ever take home an Oscar for Best Picture in early February. Together, these artistic accomplishments felt like a massive shift towards recognizing Asian influence in the American cultural fabric.

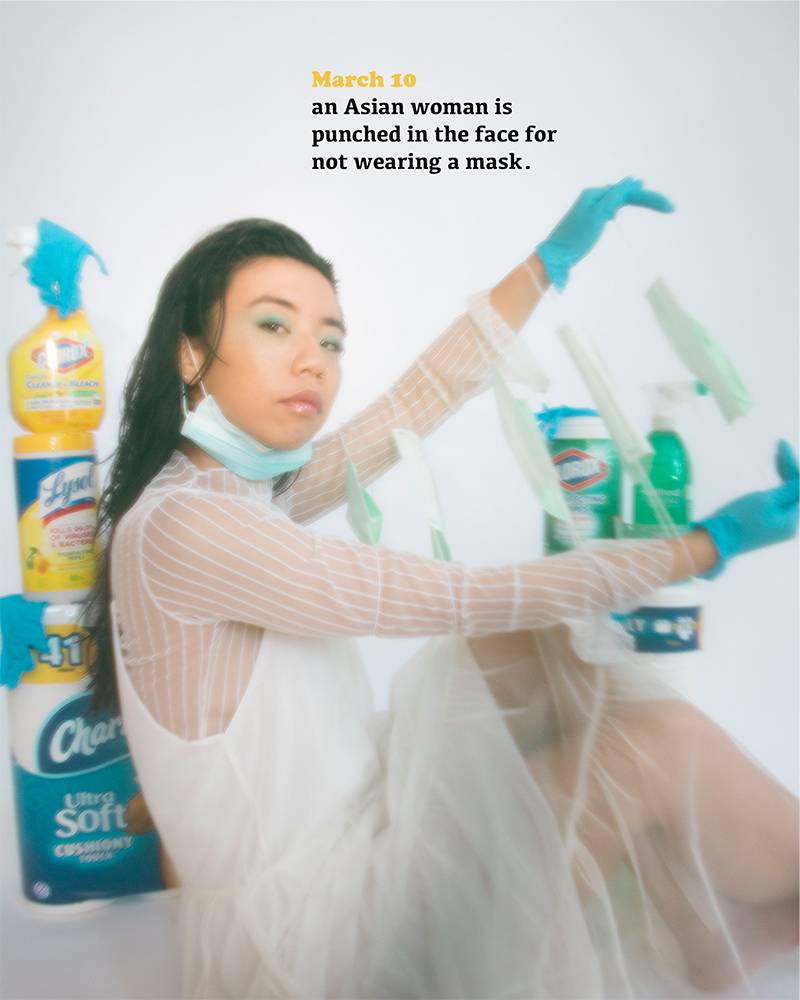

Then, COVID-19 made it to the United States. My family followed the Chinese news, so they’d been updating me on the virus’ spread since January. I wasn’t that surprised when racist attacks started being reported in February and March—but what did surprise me was how many of them took place in New York, a city I recently relocated to from the Bay Area. A masked woman was kicked in the face at Grand Street station. An Asian man doused in water while smoking a cigarette. Another was sprayed with Febreeze on the subway. A woman was punched in the face in K-town. A woman had acid poured on her outside her house.

And then, beyond New York: Student Jonathan Mok was brutally beaten on the street in London. An elder was harassed and attacked while collecting cans in San Francisco. Two people were assaulted by a group of teens at a train station in Philadelphia. A 2-year-old girl, 6-year-old boy and their father were stabbed in a murder attempt at a Sam’s Club in Texas.

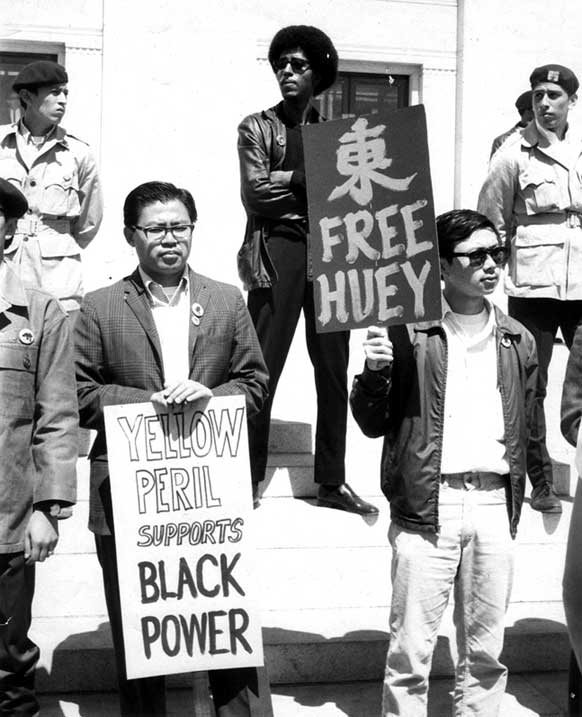

The anger that comes from seeing this kind of racial violence is raw and exceedingly visceral. It’s hard to put into words—especially for Asian Americans for whom speaking up in matters of social justice is more difficult after decades of believing that their level of privilege, created by the model minority myth, shields them from having to advocate for civil rights. This is even more complicated by the fact that silence is a traditional East Asian cultural custom. As Gu Xiao-le describes in A Contrastive Analysis of Chinese and American Views about Silence and Debate: “In … Chinese culture, communicators assume a great deal of commonality of knowledge and views, so that less is spelt out explicitly and much more is implicit or communicated in indirect ways … Silence holds a strong contextual meaning, such as showing obedience to senior people, or being a sign of respect for the wisdom and expertise of others, or disagreement while avoiding direct confrontation.”