Santa Rosa, my hometown, is a relatively serene place. You may know it as the home to Peanuts, Pliny the Younger, and a tourist-friendly food and wine scene. When Alfred Hitchcock needed an all-American small town in which to set Shadow of a Doubt, he chose Santa Rosa, quiet and idyllic.

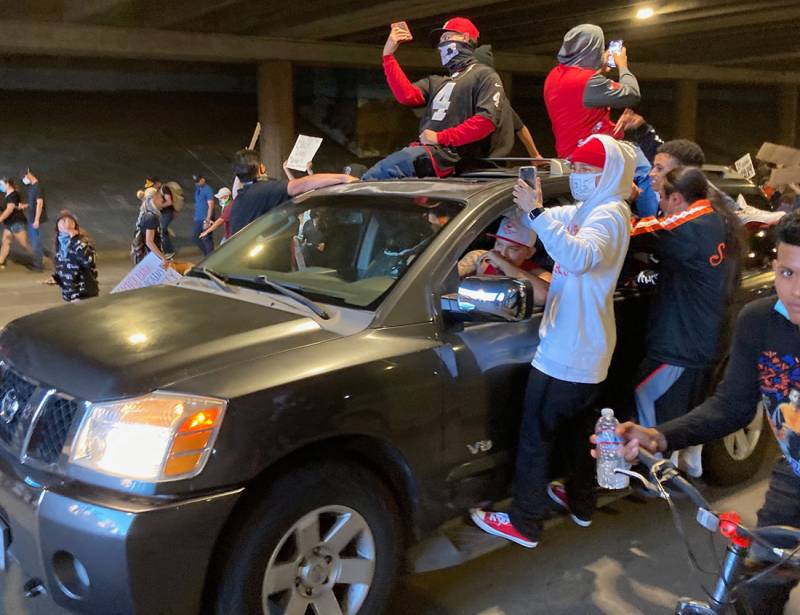

But like most cities across America, Santa Rosa has looked and sounded a little different these past 10 days. I’ve been out in the streets until after midnight on almost all of those nights, walking and talking with an incredible uprising of people, mostly young, demanding an end to systemic racism and police brutality in the aftermath of the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. I’ve lived in Santa Rosa my entire life and I have never seen anything like it.

What’s happening here is remarkable, not just on an aesthetic level—Santa Rosa can always use a little more chaos, in my humble opinion—but for the important, deeper work of necessary change. Racial oppression and acute injustice that’s long simmered under the surface here has now boiled over into public view. Ideas previously dismissed as unfeasible are being taken seriously.

And the kids—of course, it’s always the kids—are leading the way. And I’ve been following them.

Here are a few things I’ve seen and heard while reporting and live-tweeting from the front lines of the protests in Santa Rosa.

I’ve been tear gassed twice. I’ve had rubber bullets fired in my direction. I’ve watched a young woman of color wrestled to the ground by four officers and pinned to the asphalt, screaming, with a knee in her back. I’ve seen an 11-year old girl in zip ties, being led away by an officer.

I’ve seen people tumble down a hill, their scrapes bleeding, when the police chased them away for blocking the freeway. I’ve heard from a small business owner whose window was broken from a rubber bullet fired by police, which the police denied doing until shown video evidence. I’ve talked to a building manager whose roof was commandeered without his permission by police, who cut open the fence around the roof, and who left it that way without telling him, leaving it exposed to trespassers.