Before the past month, AroMa, a 22-year-old artist from Oakland, didn’t self-identify as an activist or an organizer.

“Recently my friends and I have been like, ‘What was your life before you were a revolutionary?’” AroMa laughs. “It really does feel like a past life.”

That past life was spent directing Bay Area artists’ music videos, making a debut short film ZoomBug, which premiered in 2018, and working on another musical film project, MoonBaby.

But when the protests started in Oakland in response to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derrick Chauvin, AroMa’s first impulse was to join in—after doing a little research about the risks involved. The urgency of the situation, especially after Trump tweeted “when the looting starts, the shooting starts,” was palpable. “It felt like one of those undeniable moments,” says AroMa of the president’s May 28 tweet. “If you didn’t understand what side the state is on in relation to you before, please understand now.”

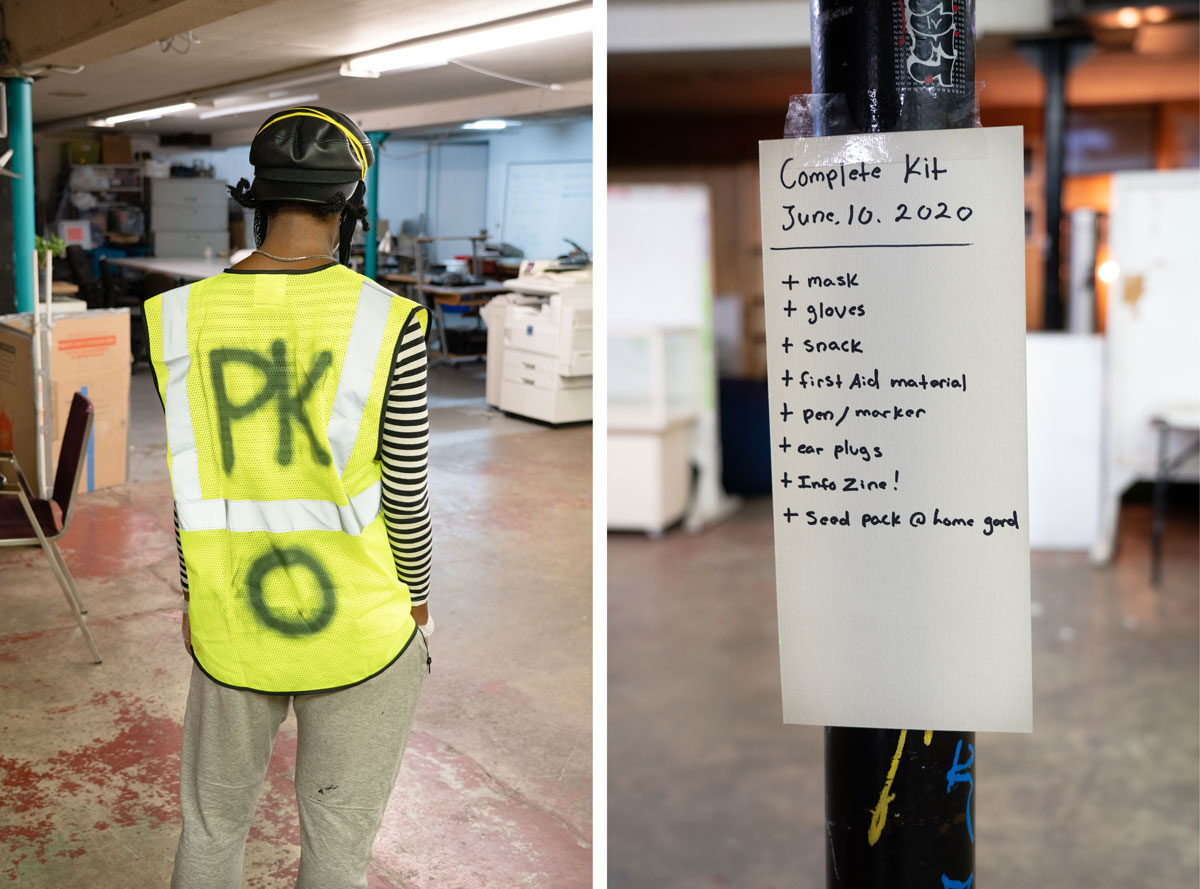

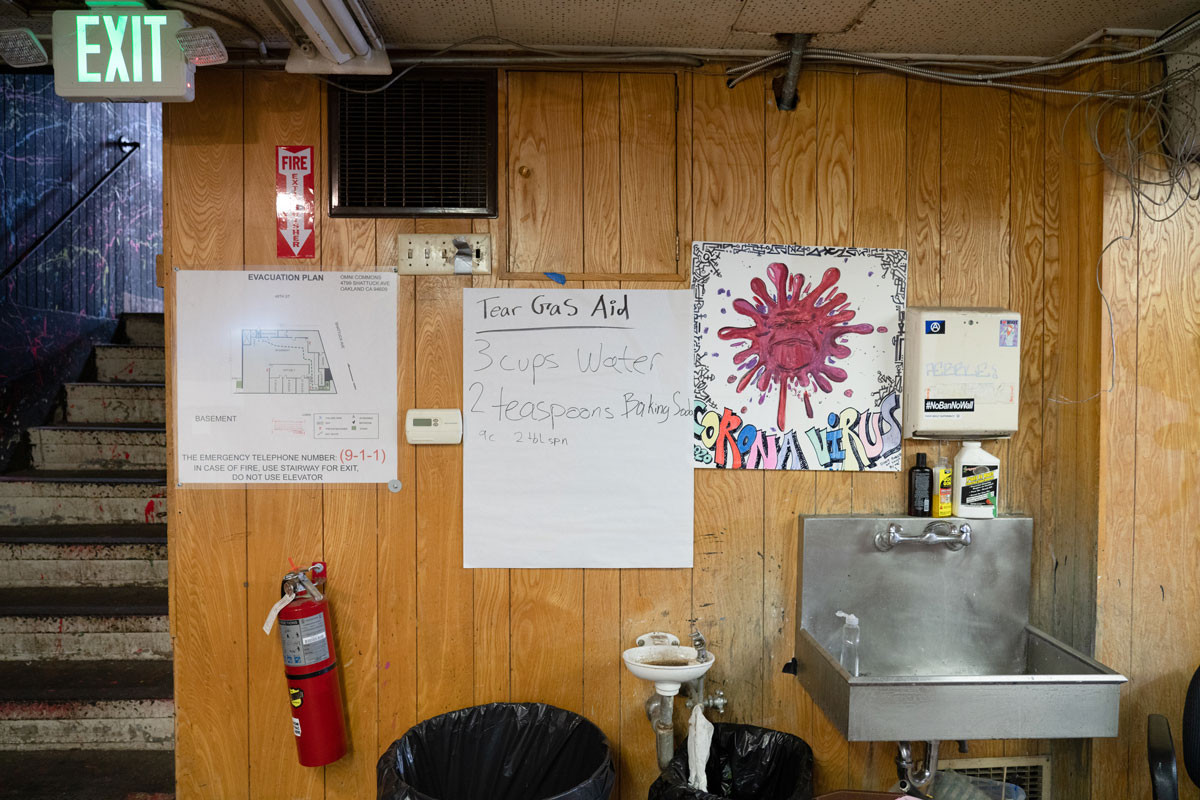

At the same time, previous experience taught AroMa, who uses they/them pronouns, to hit the streets prepared. “If you’re from here, you’re not new to protests and gatherings even if you’re not an ‘organizer/activist,’” they explain. AroMa had participated in Occupy protests while they were still in high school, and remembered seeing protesters exposed to tear gas being treated with liquid sprayed into their faces. That image from nearly a decade ago lodged in AroMa’s memory: “What’s the spray made of?”