On Oct. 5, 1891, the San Francisco Morning Call newspaper featured an in-depth report about “the shadow of misfortune” that was, at that time, hanging over Nob Hill’s most prestigious homes. The article focused on the abandoned mansions of the prominent Stanford, Crocker, Colton, Hopkins and Flood families. “Lifeless and forlorn,” the newspaper stated, “they tell no story but of pride ungratified and happiness that could not be purchased. So the shadows seem to rest on Nob Hill.”

The trail of misery was undeniable.

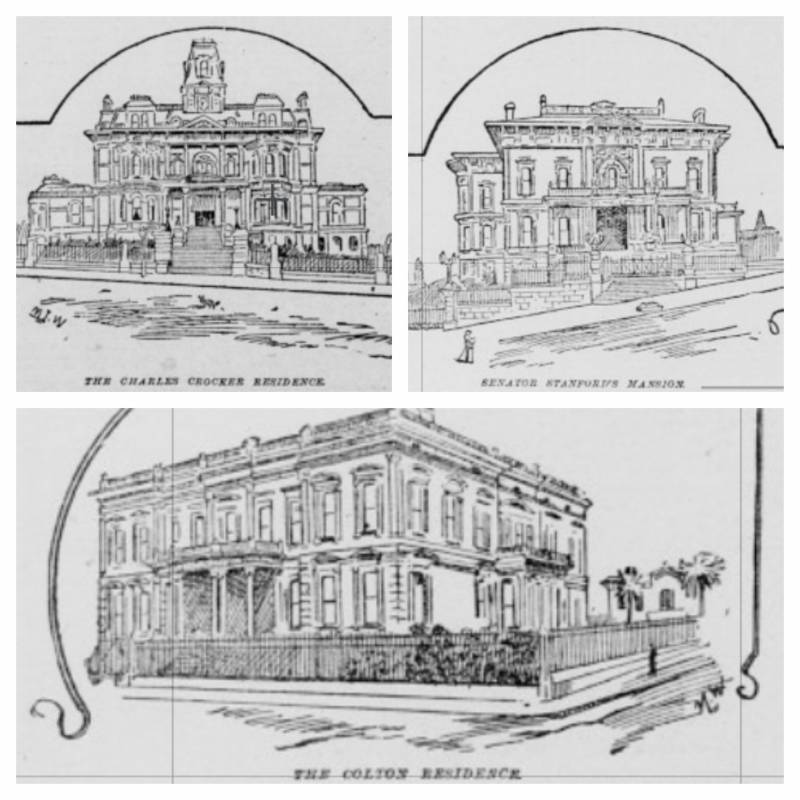

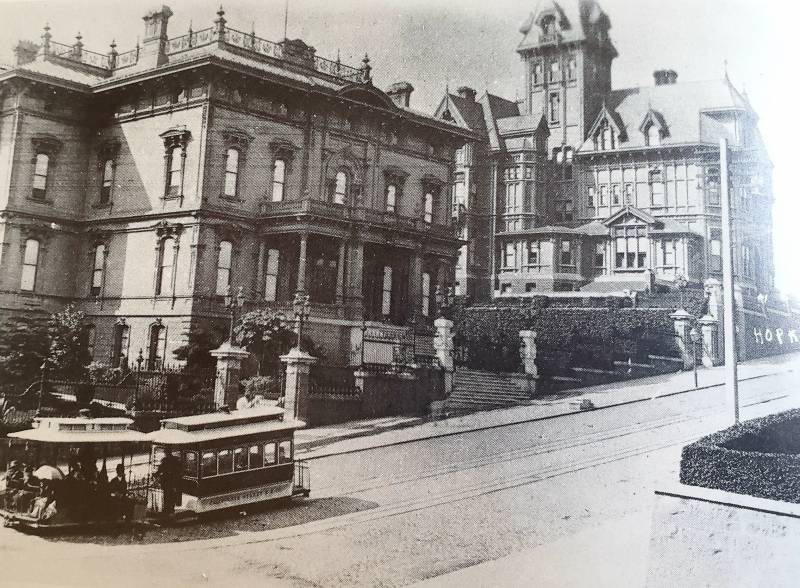

Leland and Jane Stanford abandoned their 50-room mansion on the corner of Powell and California Streets after their son died at 15 years old. In 1883, after the senator and his wife held Leland Jr.’s funeral in the 41,000 square-foot house, they moved to Menlo Park, leaving the mansion as a sort of shrine to their son. One particularly macabre feature was left visible for passersby. “In [Leland Jr.’s] old room, looking out over the bay,” The Morning Call observed, “all the belongings of his boyhood cluster undisturbed. His picture hangs before a window, the blinds of which are never drawn. To this room, a mother comes to weep. It is the shrine of her grief.”

Many of the Stanfords’ neighbors were struck with similar misfortunes.

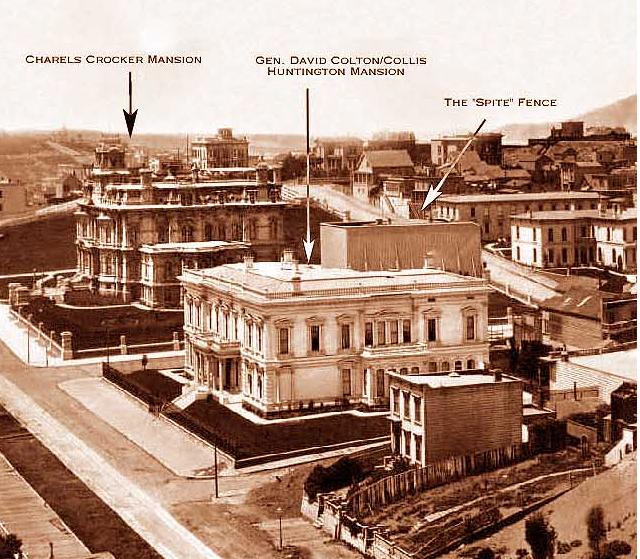

Charles Crocker, a co-founder of the Central Pacific Railroad, as well as the bank that later became Wells Fargo, had built his 25,000 square-foot home at the peak of Nob Hill (then called California Hill). His intention was to acquire and demolish the 13 houses already on the land and build on the vacant plot. He succeeded in buying 12. When the owner of the final home—an undertaker named Nicholas Yung—requested $12,000 to move, Crocker refused to pay and, instead, walled off Yung’s home behind a monstrous, 40-foot-tall “spite fence.”

Crocker died in 1888, leaving two of his sons squabbling over ownership of the house while also continuing their father’s feud with Yung. It’s remarkable that the eldest Crocker, Fred, had the energy for such pettiness, having lost his 29-year-old wife in childbirth the year before his father died. (Fred never married again and their daughter, Mary, only made it to 24.)