E

ver since the pandemic flattened our physical world into a mostly digital plane, the theater of human life has unfolded on Zoom, TikTok and Instagram. Meet-ups and breakups, weddings and divorces, childbirths and funerals all take place now in the 2D space of our screens.

Given the—sigh—current moment, the internet provides a fitting setting for one of the timeliest art projects to come out this year: The Electronic Lover, an opera released in the form of a podcast that’s set at the dawn of the internet, where the intrigue plays out in an early ’80s chatroom. Though librettist Beth Lisick and composer Lisa Mezzacappa began working on The Electronic Lover three years ago, the podcast arrives just in time for the COVID era, when seeing live opera isn’t an option and performing artists struggle to adapt. The pilot episode comes out Aug. 14, with a virtual launch party including the cast and creators hosted that evening by the Center for new Music.

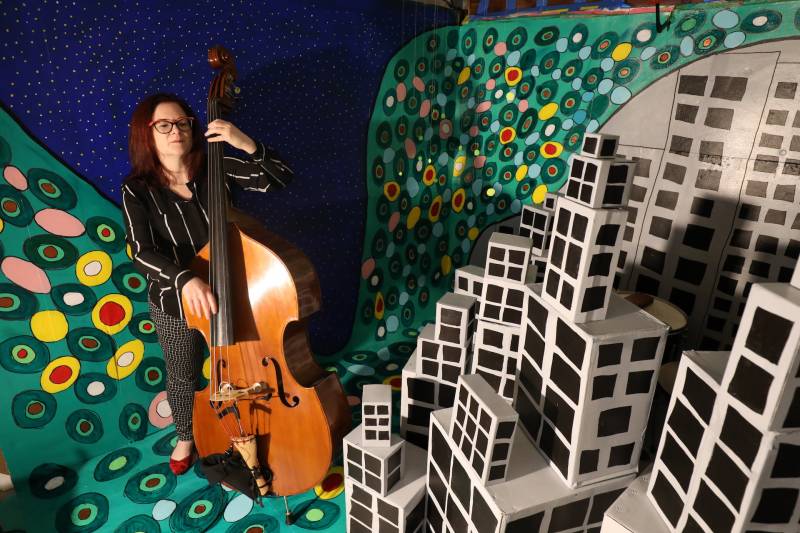

While there are podcasts about opera, as well as fiction podcasts devoted to narrative storytelling, The Electronic Lover is the first time (at least according to my research and the creators’ knowledge) that an opera has been presented in serialized episodes for streaming on Apple, Stitcher and other podcasting platforms. It’s also both creators’ first official foray into the genre, though one could say that their past endeavors prepared them for the task. Lisick, co-founder of the popular San Francisco live storytelling event Porchlight, is known for funny, gonzo-style writing about artist life. Mezzacappa is best-known as a jazz bass improviser and composer whose ambitious collaborations have pulled from literature.