Long before it became a polarizing litmus test of our new political spectrum, the story and history of undocumented migrants crossing America’s southern border was on Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s mind.

The novelist, who grew up in Los Angeles, spent her 20s in the East Bay teaching ESL and Spanish. She later worked in Oakland public schools as the assistant director of a college prep program for low-income, first generation students. When she began writing her latest novel, The New American, several years ago, she was drawn toward the complex narratives of those coming from beyond Mexico.

“For me the big story in Mexico in 2012—and this is before anyone in the mainstream news was really talking about it here—was the story of what was happening to Central Americans as they migrated north,” says Marcom, who is currently sheltering in place in Sausalito and splits her time between the Bay Area and Virginia. “They, too, are undocumented in Mexico as much as the United States.”

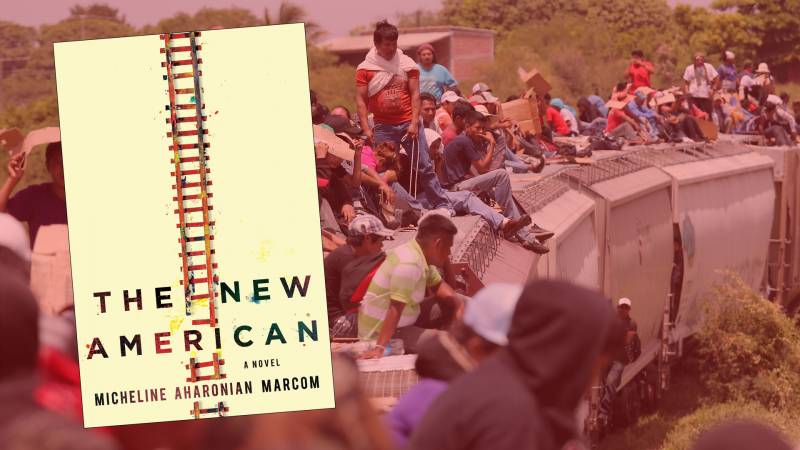

Most of The New American indeed takes place during the journey from Central America to and through Mexico—in migrant shelters and on La Bestia (“The Beast”), the infamously perilous freight train that countless immigrants use to traverse thousands of miles—rather than at the U.S. border.