The Velvet Bandit looks to the left, sizing up the street, and eyes a line of cars stopped at a red light in downtown Santa Rosa.

“Let’s wait for the light to change,” she says. “There looks like a lot of…”

“Naysayers?” her assistant asks.

“Yeah.”

Soon the light turns green, and the two speed-walk to their destination: an alcove of an abandoned building, highly visible, where thousands of people pass each day and a bright light shines at night.

Visibility is a risk for the Velvet Bandit, a street artist who doesn’t fit the stereotypical profile of a “street artist.” I can’t really tell you who the Velvet Bandit is, exactly; she operates under cover of night, and placing her art on public and private walls is, technically, not legal. This much is known: she is a single mom living in Sonoma County, and before COVID hit, she worked as a cafeteria aide at a local school, preparing lunch for schoolchildren.

As we reach the alcove, I take note of a “No Trespassing” sign, and quietly alert the Velvet Bandit.

She keeps walking briskly, unconcerned, and in a small burst of freedom—from shelter-in-place, from our toxic political climate, from her day job—she quips: “Lunch ladies don’t give a fuuuuuucccckkk!”

A minute later, the deal is done, and the wall bears a hand-painted image of Uncle Sam, wearing a face mask, with a simple message: “VOTE.”

The two women step back to assess the job. “Oh, yeah,” one says to the other. “Yeah. That looks awesome.”

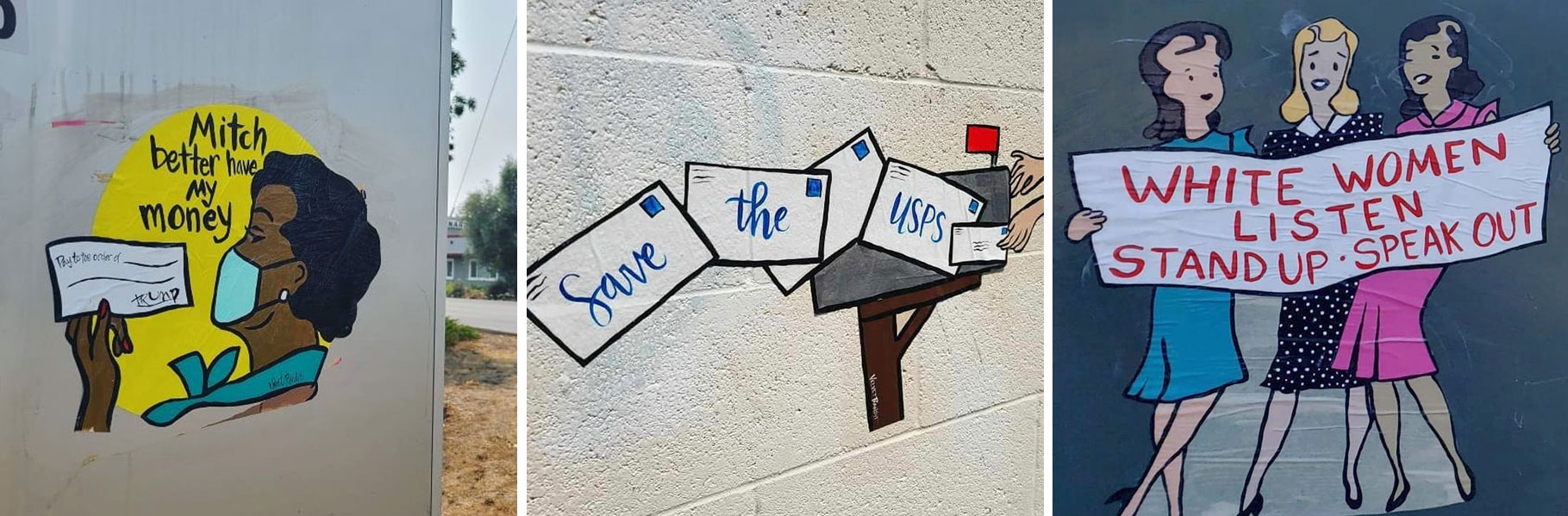

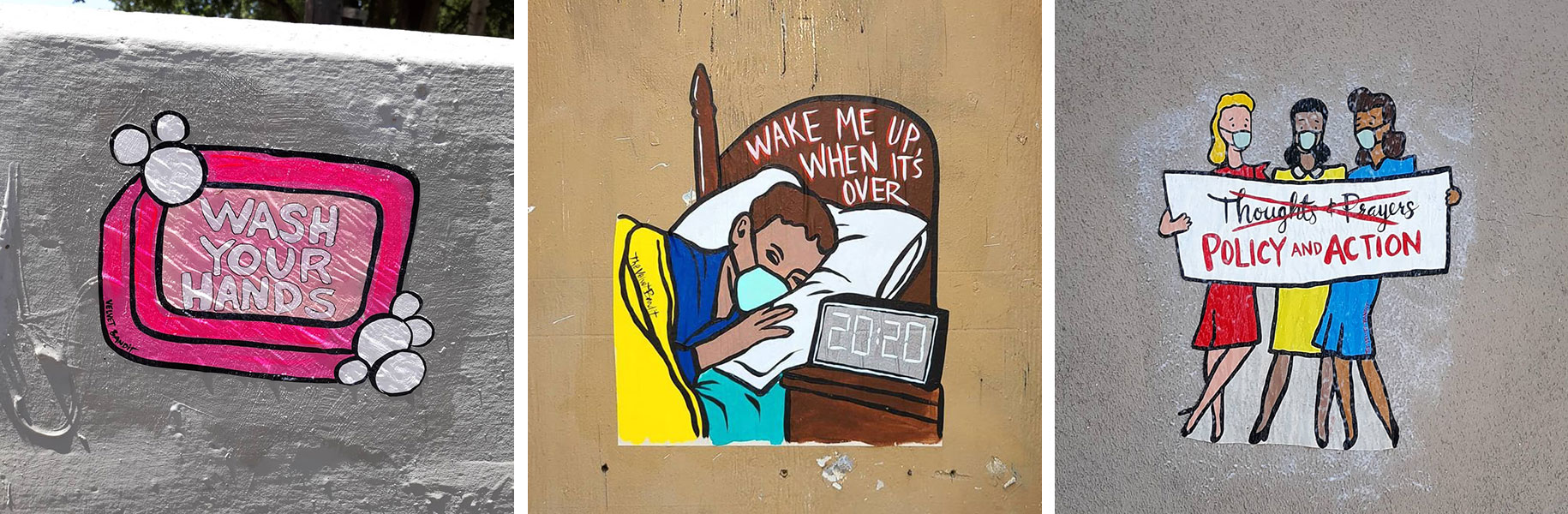

I started to notice the Velvet Bandit’s colorful paintings a few months ago, wheat pasted to walls and poles, with their positive messages for the pandemic. At the start, they bore simple reminders, like “Stay Home” and “Wash Your Hands.” Then, while everyone waited for stimulus checks, I noticed one in my neighborhood of a woman holding a check, with the phrase “Mitch Better Have My Money.”

Later, people told me they’d seen her work in other cities too: as far north as Ukiah and Willits, and in Sonoma, Sebastopol and Petaluma. It evolved, also: her paintings have lately amplified messages of the Black Lives Matter movement and the need to save the Post Office. Most of them simply acknowledge the struggle, for everyone, that is the year 2020.

So far, out in the streets at night, she and her assistant haven’t gotten caught—which is impressive, considering her work is prominent, colorful, and prolific.

“I always dreamed, like, ‘It’d be really cool to have this mom graffiti gang that goes around and puts these positive messages out,’” the lunch-lady-turned-street-artist tells me when we meet up on a recent weekend night.

In March, she says, like many, she was furloughed from her job. Shepard Fairey’s wheat-pasted art had been a longtime inspiration, and she’d kept a pile of newsprint in her studio, ready to paint. So, she says, “when I had nothing but my art supplies to keep me sane, it was the perfect opportunity.”

The Velvet Bandit has made about 600 pieces since, she estimates, putting up most of them in cities across the North Bay. Astonishingly, all of them have been painted individually, by hand. She tried making copies of her work like other street artists do, but “the vibrancy isn’t there,” she says.

So far, reaction to her work has been relatively positive. Rather than scraping her work from their walls, several area businesses owners have contacted her, either donating money or even requesting that she come put it up on their storefronts.

At the former Dollar Tree building in the Roseland district of Santa Rosa recently, a man came out and gruffly asked, “What are you doing? What agency are you from?”

She explained she was putting up art, and when he saw her work, he asked if she had any more. “And he said, ‘Put it around the whole building!’” she explains. “’And in fact, put it on those two taco trucks over there!’”