As complicated and multifaceted as it might seem, the story of Guantánamo Bay, “the world’s most infamous prison,” is actually quite straightforward. “What I realized while working on this is there’s actually a really simple story here,” says Portland journalist and author Sarah Mirk in a recent Zoom interview. “We put a lot of people in prison and we didn’t put them on trial.”

Mirk is the editor of the new book Guantanamo Voices, a series of 10 illustrated narratives based on true accounts from the prison. The book brings together a talented group of graphic novel artists from around the world, each one illustrating a different perspective on the prison, including oral histories from former prisoners, lawyers, social workers and service members.

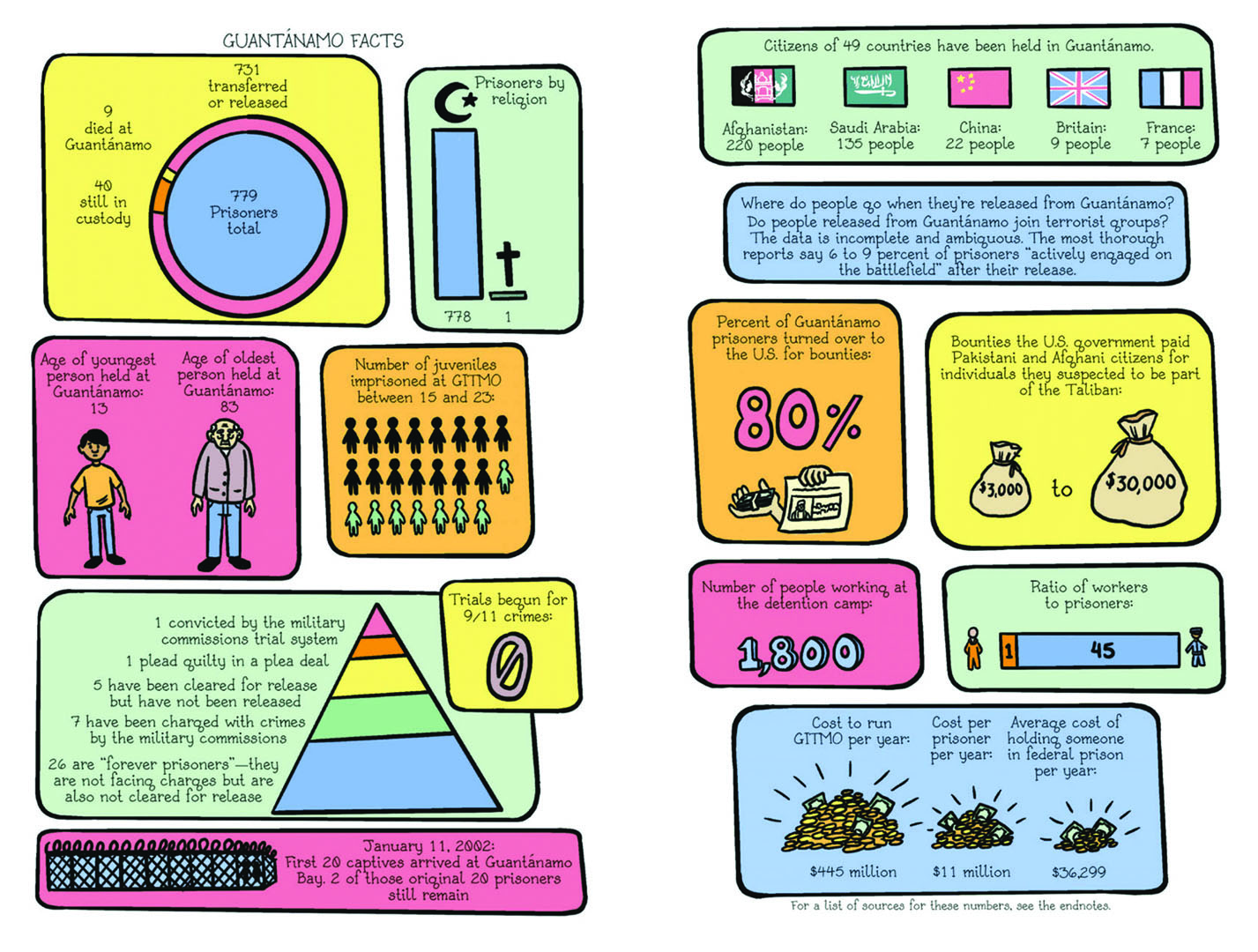

The U.S. has held roughly 780 prisoners, mostly Muslim men, at Guantánamo since 2002—and 40 people remain there still.

And yet, the prison is often a forgotten topic of recent American history; Guantanamo Voices’ illustrated format does the difficult work of making these facts accessible to a broad audience, dispelling falsehoods in the process—like the idea that all Guantánamo detainees were dangerous criminals. “A lot of Americans really bought that myth,” says Mirk. “I think it’s worth encouraging people to question the mainstream narrative—is it true? And are we actually OK with it?”

The book also prompts readers to think about what justice might look like, and how we might face this history. Berkeley artist Nomi Kane, who worked on the infographics that open the book, says this project is working to undo some of the dehumanization that allowed torture to exist at Guantánamo. While many of the facts included have been reported elsewhere, Guantanamo Voices uniquely represents individual lives, connecting the prison to other moments in history, including the present day.

The Role of Comics

While some may not see comics as a serious storytelling format, Mirk says they can “make the invisible visible.” The U.S. government has still not allowed significant access to Guantánamo Bay. At one point in the book, Mirk visits the prison on a press trip, but is made to delete a number of her photos afterwards. “It’s hard to see what’s happening there,” she says. “It’s hard to talk to the people who have been in prison there. And it’s hard to actually go and see it for yourself.”

Out of sight, peripheral to everyday Americans’ lives, “it doesn’t really seem like a real place,” she says.

In the absence of photographs, comics and the graphic novel format have the power to make people and places come to life. “You’re seeing the faces of the people who are in the stories,” Mirk says. “You’re seeing their clothes, you’re seeing where they live.” Such images, Mirk explains, can build empathy.

Layout, color and spacing all bring an emotional impact to the work. Without spoiling the ending, the book’s third chapter tells the story of Matthew Diaz, a former navy judge advocate who tried to release information to a lawyer at the Center for Constitutional Rights in a Valentine’s Day card. The story, and the way it’s told, brought tears to my eyes.