Regina Y. Evans works with a team of folks to assemble altars on Oakland’s International Boulevard, a hub for adult sex workers as well as the sex trafficking of minors.

Regina says the goal of the work is to be present for the girls—or “Beloveds,” as she calls them.

The altars are decorated with art, flowers, letters and fabrics, and since the start of the pandemic, she’s been adding hand sanitizer, condoms and PPE. Regina says her team builds these altars as an offering, and that she doesn’t directly approach the Beloveds. Instead, she allows the altars to be an opening for interactions.

For Regina, spirituality, social commentary and artistry all weave together in her mission to abolish the sex trafficking of minors.

You can see this in all her work: She’s the founder of the vintage boutique, Regina’s Door, which also serves as a safe haven for at-risk youth and survivors of human trafficking. And in addition to designing costumes for stage shows, she writes and performs her own plays, which are informed by her work in the streets of Oakland.

Below are lightly edited excerpts of my conversation with Regina Evans.

PEN: After 52 Letters, one of your more recent plays… you mentioned that one of the attendees of the play said it was “A bit much.” What was your response to them?

REGINA: It was a gentleman. When I got off stage and I went out to greet the audience, he said, “It’s almost too much.”

And my response to it was, well, you just got an hour of an idea of a young kid who’s being traffic 24/7. You just got a glimpse of it. So give thanks. Give thanks for her pain. Give thanks for her tears. That you get to be a witness just by sitting on the other side of a fourth wall.

It’s an interesting thing when you talk about trafficking because people often don’t get it. It’s almost like talking about past day slavery. People are like, yeah it was terrible, it was was really bad, but do we really think about it? Do you think about the day-to-day? Do you think about how your fingers felt picking the cotton? What about the cracks in the feet? We say that it’s bad, it’s inhumane, but we’re not thinking about the day today, the minute of what a child is having to endure. That’s what makes words and plays so powerful because you can bring that to the person. And so they can then feel it.

PEN: It’s all in the details, and that’s what you see eye to eye with the human experience, and I totally recognize that as a storyteller. There’s so much power in details. How do you go about observing and bringing in these details? Where do you pull that from?

REGINA: You know, I use a lot of my own story, the feel of my own story, the feel of what it felt like when I was healing. I asked as a couple of other people if I could use bits of their story. And then spirit. So I mix it all together. It’s not something that I’m writing or talking about that I don’t know what that intensity or what the pain of it actually feels like.

Any survivors of an injustice holds a particular and intimate knowledge of that injustice. Just because we’ve been so close to it. We know how it moves. We know how it smells. We know the wink of the eye or how the eyes move. We know all of those little things. That’s why survivors are important for any social justice movement because we know the intimacies of it.

PEN: Social justice as well as journalism: You want to get to the primary source. You want to get to the people who have experienced it. What does your abolition work look like right now in 2020?

REGINA: My work is historical and now, at the same time, because this is not a revisit, this is a continuation. The black female womb has been commodified since we hit these shores. Where has it stopped? There’s a quote from Frederick Douglass and he says something like, ‘Slavery has called itself many names and it will again call itself by many names.’

And you and I and all of us had better wake up and listen, so that we can see how this snake is going to rear its head again. And so here we are calling it a different name.

PEN: I went to the taco spot, shout out to Taco Sinaloa on 22nd and East 14th. They were just about to close the taco spot, it’s like late night. And I was just amazed at the amount of people out there working. What’s going on on East 14th right now?

REGINA: Woo! East 14th right now is lit. When the pandemic hit, like I thought I wouldn’t see as many beloveds out, and that was not the case. It’s just wild, not only the amount of young beloved, but the feel, the atmosphere. [sigh] And… you know, I never carry condoms with me… But the amount of young beloved who are like, do you have condoms? And I was, oh shoot. Yeah, I need to have condoms for them. Saraí Mazariegos from SHADE, she started bringing condoms and stuff and now we put condoms on the altars.

PEN: Paint the picture for me. What do these altars look like?

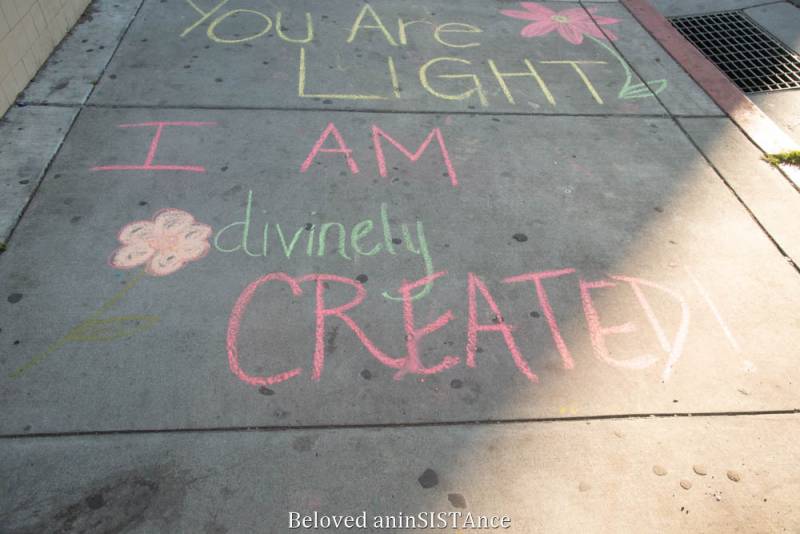

REGINA: You know, I put candy and stuff in there and make them really pretty. I always use a lot of fabric. I write them letters, and put them in there, and then I put up these signs that say, ‘You are beloved, you are beautiful. signed the queendom.’ I do that all up and down the track. I’ve been building altars on the track for a very, very long time. It was a thing that I could do without, you know, approaching the beloved. And as I was building them I’d be like, ‘I love you. I see you. You’re not forgotten. You’re not alone.’

And then when the pandemic hit, I had a dream. and in the dream I saw the track. It was like a garden. And I woke up and I was like, oh, shoot, we’re gonna build a garden on the track. And I called in all my friends and people came in strong.

So what they look like are lots of plants. Leafy plants and we also use succulents. And we also embed the altars with PPE, masks, hand sanitizers. People leave food and water. The main purpose is just to leave beauty and love.

PEN: You speak of, you know, visions come into dreams. You talk about this is the work you’ve been called to do. You’re answering the call. What is the end goal?

REGINA: So the end goal is no trafficking. [sigh] I asked this question at the end of my play. When I do 52 Letters, I say, what would you do if you knew a child was being trafficked? And I let people think about it. And then I say, What would you do if your child was being trafficked? We don’t see that these children are our children, so trying to make the connection that these are all of our children.

You know, I don’t understand how we don’t view them through the lens of our own heart. Or the eyes of our own souls. They deserve to be cradled. And they deserve to be held by us with all that we are.

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.