These are unprecedented times. At least it seems like everyone is saying so, but is it true? There’s the global pandemic, attacks on democracy by political leaders, racist violence by police, environmental destruction, and so much more. But which of these is unprecedented? Potawatomi philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte uses the term “ancestral dystopia” when writing about how our current world would be a dystopia to the ancestors of Indigenous people.

At YBCA, Art is a Powerful Tool for Envisioning a Less Complacent Future

That is to say, the crises are ongoing rather than novel to our times. This perspective is central to AFTER LIFE (we survive), a multimedia group exhibition at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (also offered as an online exhibition), which centers Black, brown, Indigenous, queer and trans artists from communities that have been among the most affected by the precedents to what is now being called unprecedented.

Courtney Desiree Morris’ 2019 series of photographs titled Solastalgia draws on a concept of the same name from environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht. It describes a distress caused by environmental change—or “a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at ‘home.’” Morris’s series (some photographs are only available through the online exhibition) evinces this sense of loss in Mossville, Louisiana, a town her maternal family has lived in for more than 150 years. The predominantly African American community has been ravaged by pollution, exceptionally high levels of toxins in residents’ bodies, and severe health issues as a result of nearby chemical plants.

Some of Morris’ photographs resemble the kind often seen in representations of rural towns suffering under capitalism. One pictures an apparently abandoned pink pastel clapboard house with peeling paint, another documents a residential land plot with only a concrete driveway, foundation and stairs remaining. To be sure, these evoke a sense of nostalgia and loss, but these feelings are complicated by photographs of the town’s residents.

In one photograph, a large group of older adults gathers at what appears to be a high school reunion. The exact mood of the moment is unclear, but there is nonetheless a celebratory or convivial air about the event. Mossville is no ghost town. But what to make of this photograph in light of the violence residents face? Is this a portrait of survival or a portrait of individuals experiencing loss and environmental racism? Maybe it is both, and in that sense, it is a reminder that crises that may feel to some like science fiction are the everyday realities for much of the world.

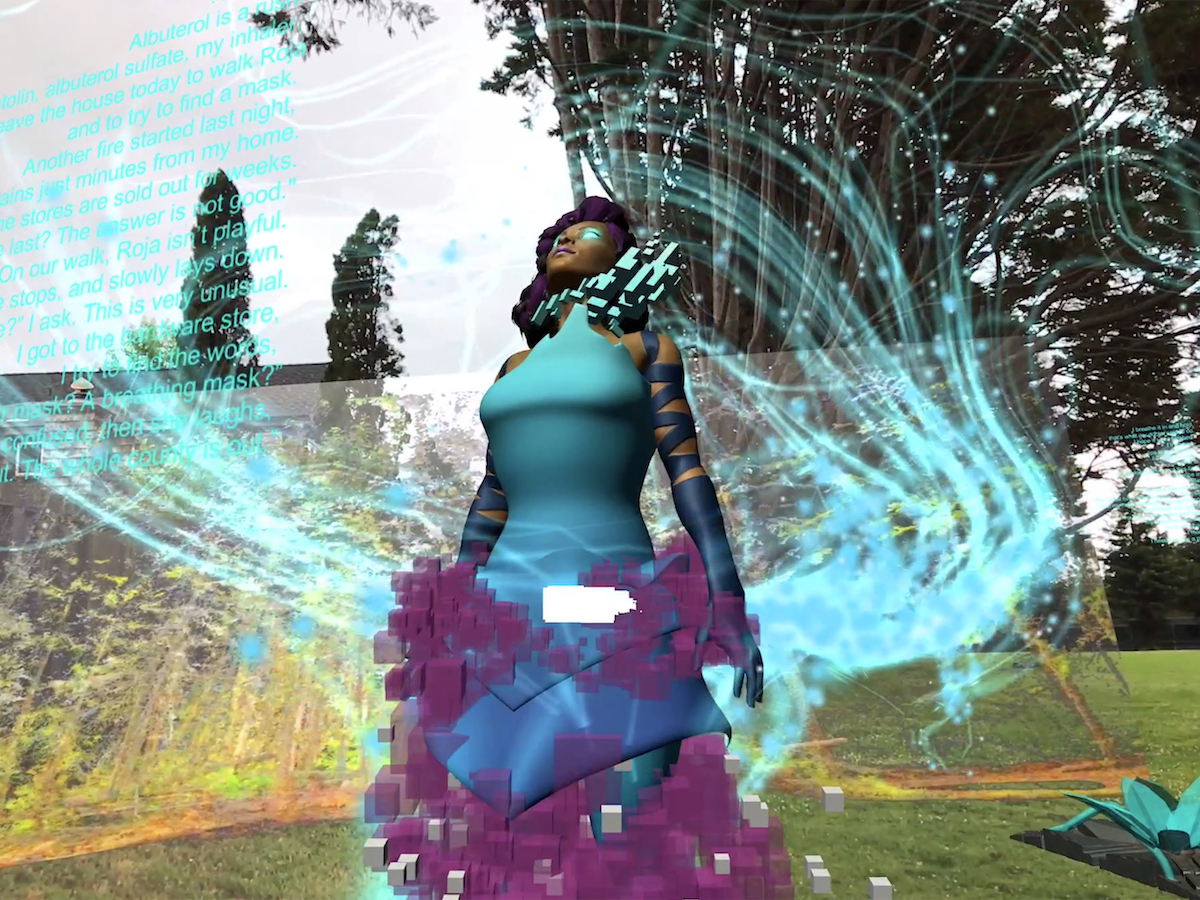

Sin Sol / No Sun (2020), an augmented reality experience by micha cárdenas, takes another approach to the idea of precedent by showing that the history of future disasters is now. In the iPhone game, which overlays computer graphics over one’s surroundings, Aura, a trans latinx AI hologram, tells of a past climate collapse that is in fact our own present. Aura speaks to players in terms that may feel like science fiction and fact at the same time, such as, “When I walked into the living room of my pod, the orange light shining through the blinds told me the smoke was back.”

This familiar language draws a connection between Aura’s time and our own. And if we are the precursor to the destruction of Aura’s time, we should be able to see in history the precursors to the crises of our own time. Sin Sol / No Sun resists the idea, present even during times of crises, that the future is bound to be bright—that history is on a march toward justice, that we just need to have faith and be patient.

But if Morris’ photographs show how the crises of the day are nothing new, and if cárdenas’ piece cautions against overly optimistic visions of the future, these artworks do not emphasize despair or a sense of futility. Art can be a powerful tool for visioning the future, a power that does not seem lost on the artists of AFTER LIFE (we survive).

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s kaleidoscopic animated short film Grace and Mercy 556, for example, envisages a future revolution that draws on queer futurism, Islam and the occult. Likewise, the group Coven Intelligence Program, which describes itself as a techno-botanical coven, imagines the revolutionary potential of engagement between plants and machines. The group’s SpellWeaver app (only available through the online version of the exhibition), allows users to create and invoke their own spells, which are converted into cryptic weaving patterns. When one invokes a spell, they are also being called on to invoke a future of their making. These may be unorthodox calls to action, but they can be invigorating and inspiring, and they can help resist complacency and complicity.

‘AFTER LIFE (we survive)’ is on view in YBCA’s windows and online through Jan. 24, 2021. Details here.