The first show I visited in 2021 was also a last: Gallery 16’s final exhibition in the ground-floor SoMa space it’s leased since 2005. This moment has been coming—the building’s new owner wanted to raise the rent more than threefold, and gallery founder Griff Williams long ago negotiated their time in the space till the end of January. But what he didn’t expect was to still be looking for Gallery 16’s next home.

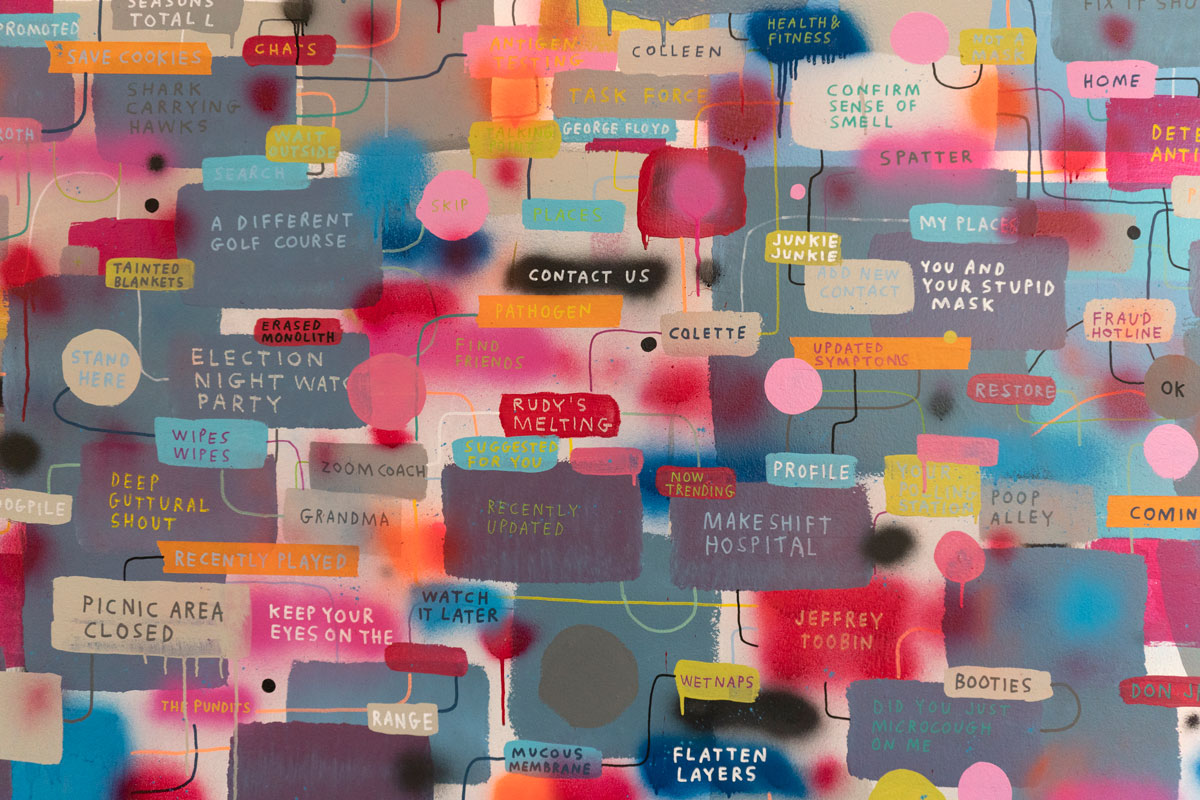

The show, The Violets in the Mountains Have Broken the Rocks, is a direct outcome of the move, the result of packing up lingering objects and editions and seeing them in a wholly new light. Just one work was made for the show, a 40-foot-wide mural painted by Tucker Nichols that ties together the key words and phrases of life during a pandemic. Among them: “Brian you are muted,” “droplet,” “do you grind your teeth” and “the orange day.”

It’s a glossary of newly relevant terms organized into a chaotic mind map. Against that backdrop, the rest of the objects in the show arrange themselves like prescient talismans or examples of better times (both past and future). The show is, for the most part, encouraging. Its namesake is a delicately embroidered linen cloth by Cliff Hengst, bearing the final lines of Tennessee Williams’ play Camino Real, a message that in this context reads as the slow yet eventual triumph of art and beauty over seemingly insurmountable adversity.

The sentiment of Hengst’s text is echoed in a neon light piece by Meryl Pataky, visible through the gallery’s enormous 3rd Street-facing windows. Her hand-shaped letters glow blue: “We have done so much with so little for so long that now we can do anything with nothing.” It’s a quote with a nebulous origin—Mother Teresa? Konstantin Jireček? the U.S. Military?—but one that would have looked right at home last summer, in the upraised arms of a Black Lives Matter protester.

The show has a loose curatorial construct, in part because nearly everything reads differently after 2020. This means some of the smallest details in the group show are the most poignant. Atop Libby Black’s painted paper trompe l’oeil sculpture Silver Lining is a replica of a House of Prime Rib matchbox, a reminder of precariousness of the Bay Area restaurant industry, and just how many beloved spots we’ve lost in the last year.