Gould is the co-founder of the Sogorea Te Land Trust, an Oakland organization that seeks to “rematriate” the land and literally give it back to Indigenous people. In numerous talks and interviews, she’s pointed to the fact that Native Americans are often spoken of as if they’re part of America’s past, when they’re still here, contending with a genocide that’s not openly acknowledged as a genocide, along with centuries of broken treaties and ongoing disenfranchisement and erasure. Giving the Ohlone people their land back, and being good guests on that land by offering them material support, is a way to back up words with actions.

A

merica has never created much space for mourning and rage at the injustices against Indigenous and Black people, which stands in contrast with the ways other countries have recovered from genocides and other atrocities. These approaches may not be perfect or universally celebrated, but surely they’re better than hundreds of years of gaslighting and sweeping facts under the rug.

After the end of apartheid, South Africa launched a Truth and Reconciliation Commission where victims of human rights abuses could give their testimonies and receive reparations and rehabilitation; likewise, perpetrators could publicly admit wrongdoing and express remorse.

Germany paid reparations to Holocaust survivors. In contrast, the United States paid reparations to slave owners—not the people whose lives those slave owners stole. In 1865, President Andrew Johnson actually took back land that had been awarded to a group of formerly enslaved people in the “40 acres and a mule” campaign—and returned it to their former captors.

Another country torn apart by violence, Rwanda, has had an ongoing reconciliation campaign to heal from its 1994 genocide, in which the government encouraged Hutu citizens to slaughter over a million Tutsi ethnic minorities. Rwanda is in many ways a repressive state, but surely there’s something for Americans to learn from its practice of requiring all able-bodied adults to take part in monthly community service more than two decades later. Imagine what America would gain if all of us, regardless of class and ethnicity, pitched in to make sure our communities were clean and everyone had access to resources. That could be a real step towards unity and healing.

We can’t change the past, but we can chart a path forward. One of America’s undeniable truths is an enormous racial wealth gap; fighting for affordable education, accessible housing and fair wages are steps in the right direction.

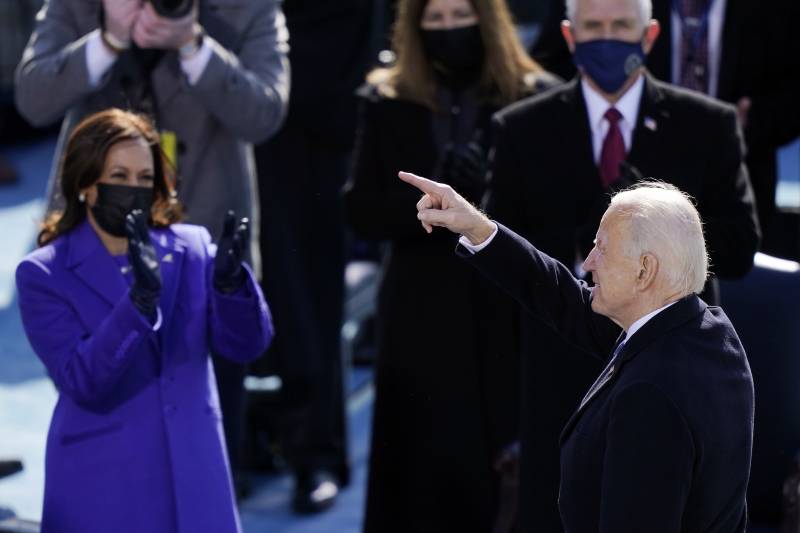

What could that look like? “Black folks and Indigenous folks and people who have been interred in this country should be able to go to whatever school for free, always. [They] should be given grants—not loans—to buy homes to establish a little bit of generational wealth,” Merin says. “People in poor neighborhoods should be able to have access to good and healthy food, and it shouldn’t cost an arm and a leg to get it. … Those are things we know the country can do. It’s just a matter of whether the country is willing to do it. For example, is Joe Biden willing to lose some of his centrist social capital to wipe out school debt?”