Clocking in at under three minutes, Astria Suparak’s video Virtually Asian is a fecund proof of concept for what could be an entire feature length film in the form of an illustrated essay. Made with materials clipped from an ongoing research project on the science fiction culture industry, the resulting collage creates a highly affecting argument on the erasure of Asian people from the canon.

The work is part of Berkeley Art Center’s digital exhibition The Option To…, launched while the space was closed due to the pandemic, which includes commissioned projects by Bay Area artists Kimberley Acebo Arteche, Roya Ebtehaj, Feral Fabric, Dionne Lee and Adia Millett.

Suparak’s piece is immediate and her voice, narrating the words, is melodic and compelling. The over-dubbing of her acerbic observations on blockbuster films is a compelling prelude to other iterations of her work that will appear in fragments across digital platforms.

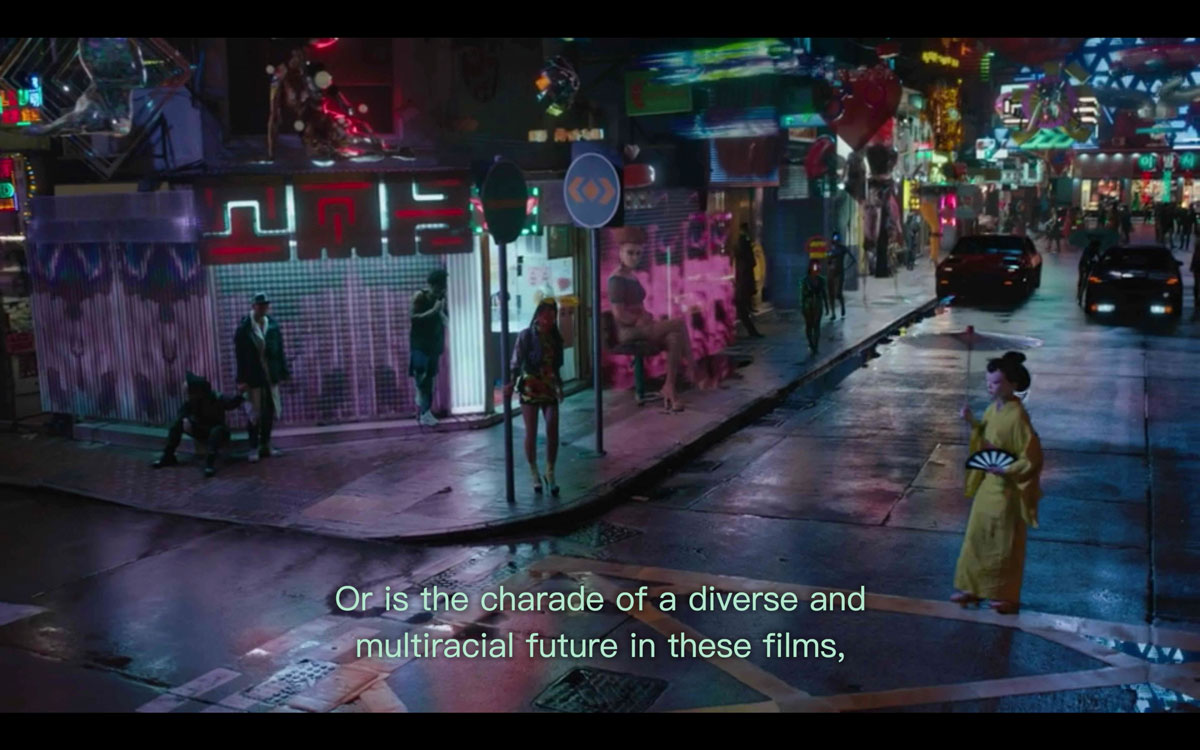

American science fiction films are often guilty of what media theorist Wendy Chun calls “high-tech Orientalism.” The term originates in Chun’s essay “Race and/as Technology or How to Do Things to Race,” which includes a reading of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, a book credited for creating the term “cyberpunk.” Looking at the crude assemblage of Asian cultures, objects, and practices casually mixed together to build the dystopian future that Gibson’s white characters inhabit, Chun writes that “high-tech Orientalism is a process of abjection—a frontier—through which the console cowboy, the properly human subject, is created.”

In a similar line of thought, Suparak writes that “Asians are used as scenery in white-made media, as a shorthand to indicate a ‘multicultural’ or ‘foreign’ place. But foreign to whom? Asians have been on record as living here since at least the 1600s, before the U.S. even existed.” In Virtually Asian, this critique overdubs footage of white protagonists in science fiction films walking past holograms of Asian women.