In 2005, after over twenty-five years years, playwright August Wilson completed his 10-play Pittsburgh Cycle—a tribute to a century’s worth of Black experience, and widely considered one of the masterpieces of contemporary American Theater. So it’s thrilling to encounter a 21st century cohort of playwrights seeking to match that achievement. Locally, playwright and costume designer Regina Evans is working on a 10-play cycle called Infrastructure, using household objects as departure points for plays connecting them to the long history of slavery, both historical and modern. And in Chicago-raised Erika Dickerson-Despenza’s projected 10-play cycle, the central focus of each will be the reverberating effects of Hurricane Katrina on the still-displaced Katrina Diaspora.

In [hieroglyph]—the second play of Dickerson-Despenza’s series, which uses lowercase names for all its characters—a pair of storm-tossed, Hurricane Katrina evacuees wash up onto Chicago’s urban shore, their transition to the north far from smooth. The adolescent davis (Jamella Cross) is 13 and having trouble settling into her new school, except for art class, where she excels. Her father ernest (Khary L. Moye), a janitor at The DuSable Museum of African American History, is concerned for her, stymied by her falling grades and (to him) unexplainable mood swings. That davis’ mother has chosen to stay behind in New Orleans is another source of tension for them both, and it’s clear that as a family unit they have much to mourn.

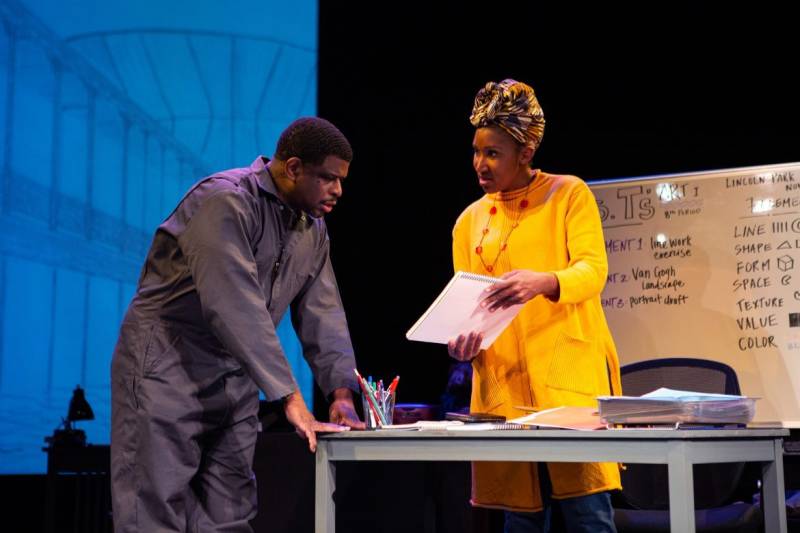

But it’s davis’ artistic talent that connects much of the play’s activity. Her detailed sketches and portraits are given prominence via a series of projections (designed by Teddy Hulsker), and many scenes begin or end with her poring over her sketchbook or discussing the relevance of one or another of her drawings. As ms. t. (Safiya Fredericks) the art teacher notes, they’re remarkably realistic and assured, but each are marked with an indecipherable character, like a cross. “Hieroglyphic,” ms. t. calls them, as she shows them to davis’ father. Neither of them can decipher them, though, and davis is reluctant to explain her artistic choices. At one point she reveals only that her portraits connect to her memories of New Orleans, and that by committing them to paper, she is exorcising them from her body. This telling compartmentalization remains a mystery to her teacher and her father—until it doesn’t.

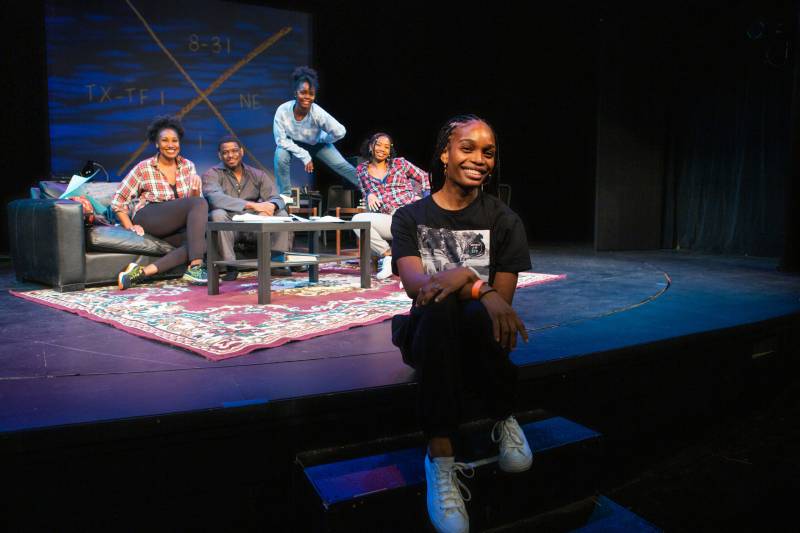

As davis, Jamella Cross deftly portrays a lanky, reserved teenager processing the physical and emotional trauma that both haunts her dreams and keeps her closed in on herself. Meanwhile, her sympathetic new friend leah (Anna Marie Sharpe) tries to teach her how to party South Side-style and diligently tutors her in algebra. Although neither actor is an actual teenager, they both manage to embody the spirit of teenhood in the easy cadence of their banter—the way they simultaneously appear to be sizing each other up and yet admiring what they see. Meanwhile Fredericks and Moye wear their mantles of adulthood with more gravity, but with no less grace. As ms. t., Fredericks draws careful boundaries around her that prove more permeable, less protective, than she’d like. Even her accumulated knowledge of African-American art history cannot completely block out her own complicated history, a fragile core that she tries desperately to keep hidden. And Moye, as ernest, carries worry etched on his face as stark as the mysterious hieroglyphs in davis’ drawings, even while he perpetuates his own cycles of careless harm. But what does not feel careless in the slightest is his deep concern for davis and his inability to pinpoint just what it is that she needs.

One of the play’s most dramatically surprising moments is a makeout session between Fredericks and Moye, not only because it takes an unfortunate turn, but because an onstage kiss feels like an act of sheer daring after a year of physically distanced theatre-making. In an article about the co-production in American Theatre Magazine, San Francisco Playhouse’s artistic director Bill English describes the process for getting this kiss approved by Actor’s Equity, including a period of enforced solitary quarantine for the two actors involved, and filming their scene out of sequence before coming into contact with the other actors. The initial effect was as electrifying as if I’d just witnessed a scandalous ankle reveal in the Victorian era, so pent-up has my need for in-the-same-room performance been.

![Jamella Cross as davis and Khary L. Moye as ernest in '[hieroglyph]' by Erika Dickerson-Despenza.](https://ww2.kqed.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2021/03/SFP-LHT_hieroglyph_Jessica-Palopoli_1-scaled-1-800x533.jpg)