United Artists, however, wasn’t an ordinary film studio, and Schlesinger, reeling from the commercial disappointment of his movie adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd, proved willing to embark on the “especially risky gamble” of turning it into a movie.

The film as we know it almost didn’t happen. Schlesinger and producer Jerome Hellman had difficulty finding a screenwriter who wanted to take the project on—Truman Capote turned them down, and Gore Vidal told them the novel was “trash” and that they should adapt his novel The City and the Pillar instead, Frankel recounts. But Waldo Salt agreed to write the screenplay, and the producer and director turned to casting the movie.

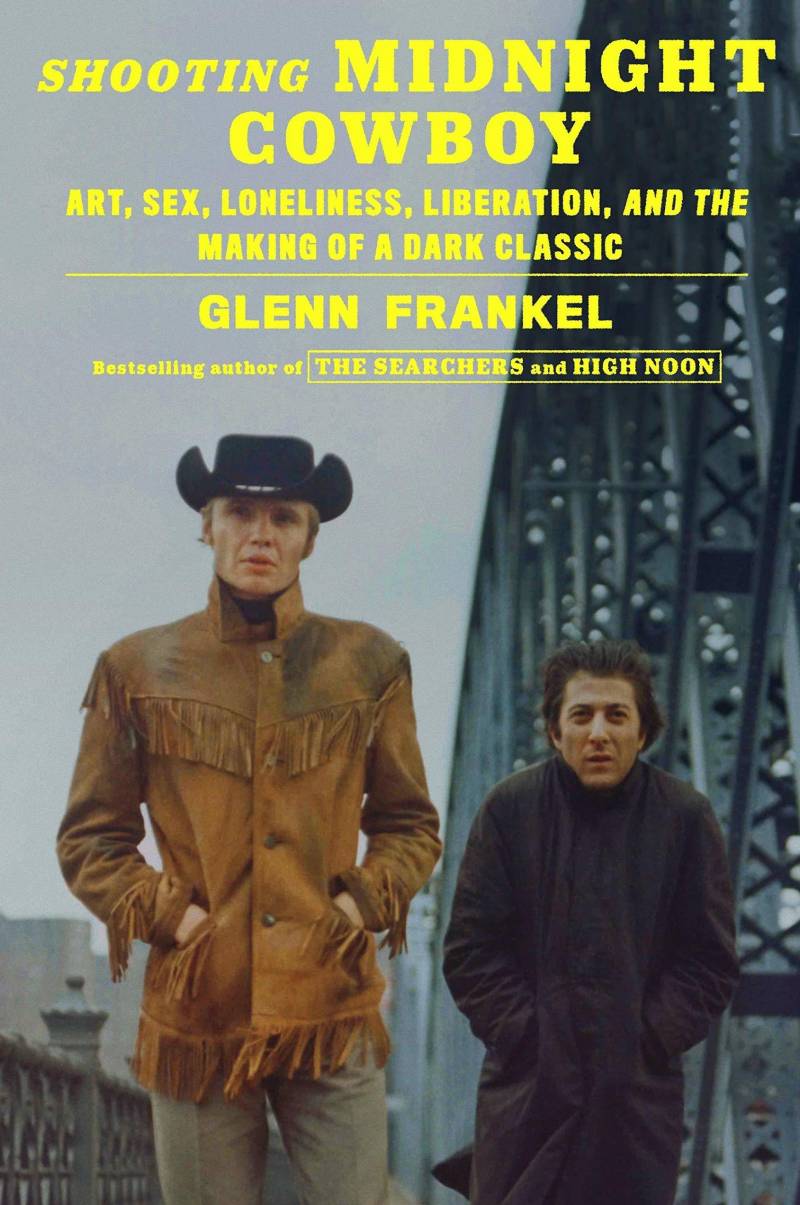

That wasn’t easy, either. “Schlesinger didn’t want either Voight or Hoffman in his movie, and looked far and wide for alternatives,” Frankel writes. He eventually changed his mind, and started shooting the film, although that turned out to be a slog: “The one thing practically everyone involved remembers about the filming of Midnight Cowboy is that the man in charge didn’t seem to enjoy it very much.”

The shoot itself was a bizarre one—the crew used “stolen shots” in the movie’s New York scenes, meaning the extras in the movie weren’t actually aware they were being filmed. The extras in the Texas shoot were aware, but they weren’t told what the movie was about, and many were incensed once they found out, Frankel writes.

The movie was a surprise hit upon its release despite some skeptical reviews from the likes of Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael. Nevertheless, it won Schlesinger an Oscar for directing, although Hoffman and Voight lost out to John Wayne, who praised the acting in Midnight Cowboy while dismissing the film as a whole with a characteristically homophobic remark.

Histories of filmmaking can easily turn into inside baseball, interesting only to film students and the most dedicated cinéastes, but Frankel does a remarkable job telling the story of how the movie happened. He’s such a gifted storyteller that you don’t even have to be familiar with the film to find the book fascinating. (You really should see the movie, though, if your emotional state allows it.)

Frankel provides ample context for the movie, painting a vivid picture of New York in the 1960s, when the city was down on its heels, with whole neighborhoods—including one used as a setting for the film—essentially being written off. He also points out how remarkable the film’s treatment of homosexuality was—although Voight’s and Hoffman’s characters are straight, Voight’s character has sex with men to earn money, a shocking plot point at the time. “[G]ay characters could appear openly on screen but only in situations that made clear their misery and depravity and that resulted in dire consequences for all involved,” he writes.

Still, Frankel points out in his excellent analysis of the film, it was hardly unproblematic. “The movie at times emits a noxious homophobia” and “is not kind to women,” he argues. One of the movie’s most difficult scenes to watch depicts a gang rape; Jennifer Salt, who played the victim, says the shooting of the scene traumatized her.

That Frankel is willing to point out that the movie is flawed is part of what makes the book so essential—Shooting Midnight Cowboy is a history, not a paean, and he asks viewers to reconsider what the movie meant, not just to American culture, but to the cast and crew who made it. Frankel’s book is a must-read for anyone interested in cinematic history, and an enthralling look at Schlesinger’s “dark, difficult masterpiece and the deeply gifted and flawed men and women who made it.”

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit NPR.9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))