In her latest exhibition, Oakland artist Stephanie Syjuco powerfully implicates photography as one of imperialism’s most effective tools. Made by mining archives for images of Indigenous Filipinos, her show at Catharine Clark Gallery, Native Resolution examines photography, anthropology and archiving as overlapping knowledge structures that shape both imagination and American history. The resulting (and absorbing) multimedia installation considers the effect and force of institutional practices that bury racism in historical records.

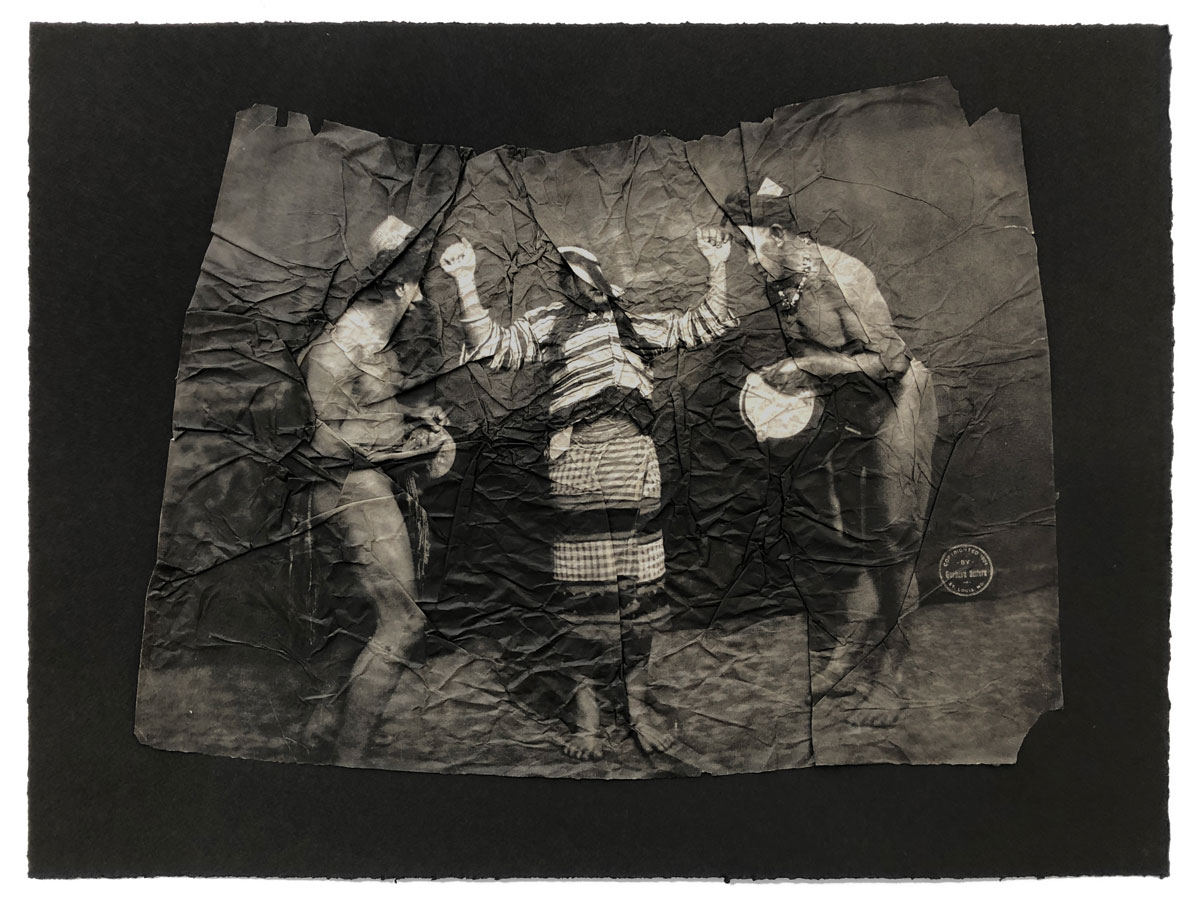

During a two-week artist residency in 2019 supported in part by the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Syjuco plumbed the city’s archives for pictures of the Philippine Reservation, the 47-acre site within the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The result is Block Out the Sun, a five-minute video presented in the gallery’s media room, in which black-and-white photographs appear and disappear on-screen, synched to the sound of a camera shutter.

As archival records, the images purportedly record the inhabitants’ cultural, religious and domestic activities as they were displayed to curious fair audiences. As extensions of the imperialist gaze, the photographs capture a glimpse of life in a “living exhibition” (read: human zoo). The installation was not the first of its kind, and it was wildly popular with world’s fair organizers and visitors. (In part, for for how such exhibitions reified presumed racial difference.)

Syjuco inserts herself in this spectatorial re-enactment by placing her hands over the photographed subjects, shielding them and refusing our want to see. Watching the images linger briefly on screen felt like watching a family slideshow, but it wasn’t my family, and I wasn’t sure I should be seeing it. Even with Syjuco’s protective intervention, I engaged the same lurid privilege of looking that so many white visitors to the St. Louis fair experienced more than 100 years ago. I strongly recommend gallery visitors start their visit to Native Resolution with this piece.

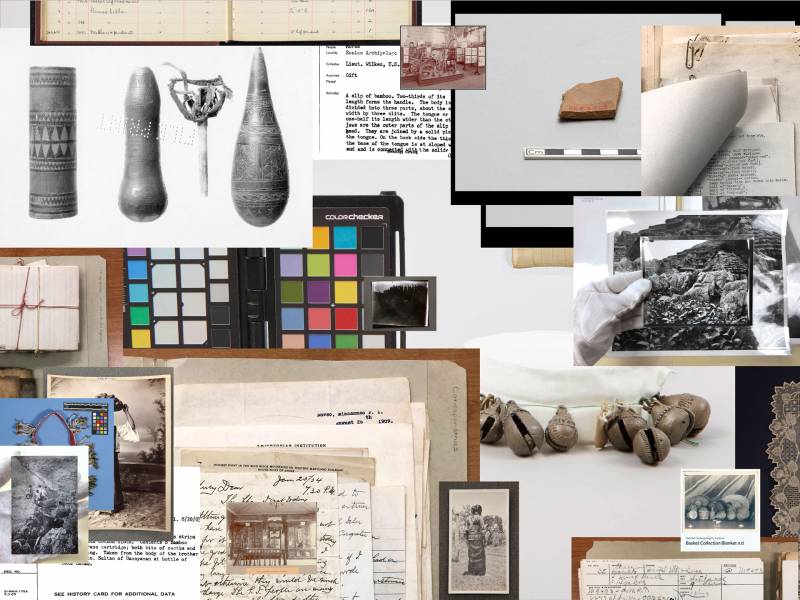

Other artworks in the show show Syjuco investigating even larger archives—as a 2019/2020 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow, she dug into the National Museum of American History and the National Museum of Natural History’s Department of Anthropology for representations of Indigenous Filipinos. In 1898, at the end of the Spanish American War, the Philippines was one of three colonial holdings (along with Guam and Puerto Rico) that Spain ceded to the United States by the terms of the Treaty of Paris. In that moment, the populations living in these newly acquired colonial outposts began to enter American historical records not as discrete individuals endowed with agency and innate human rights, but as biological and anthropological specimens to be studied.

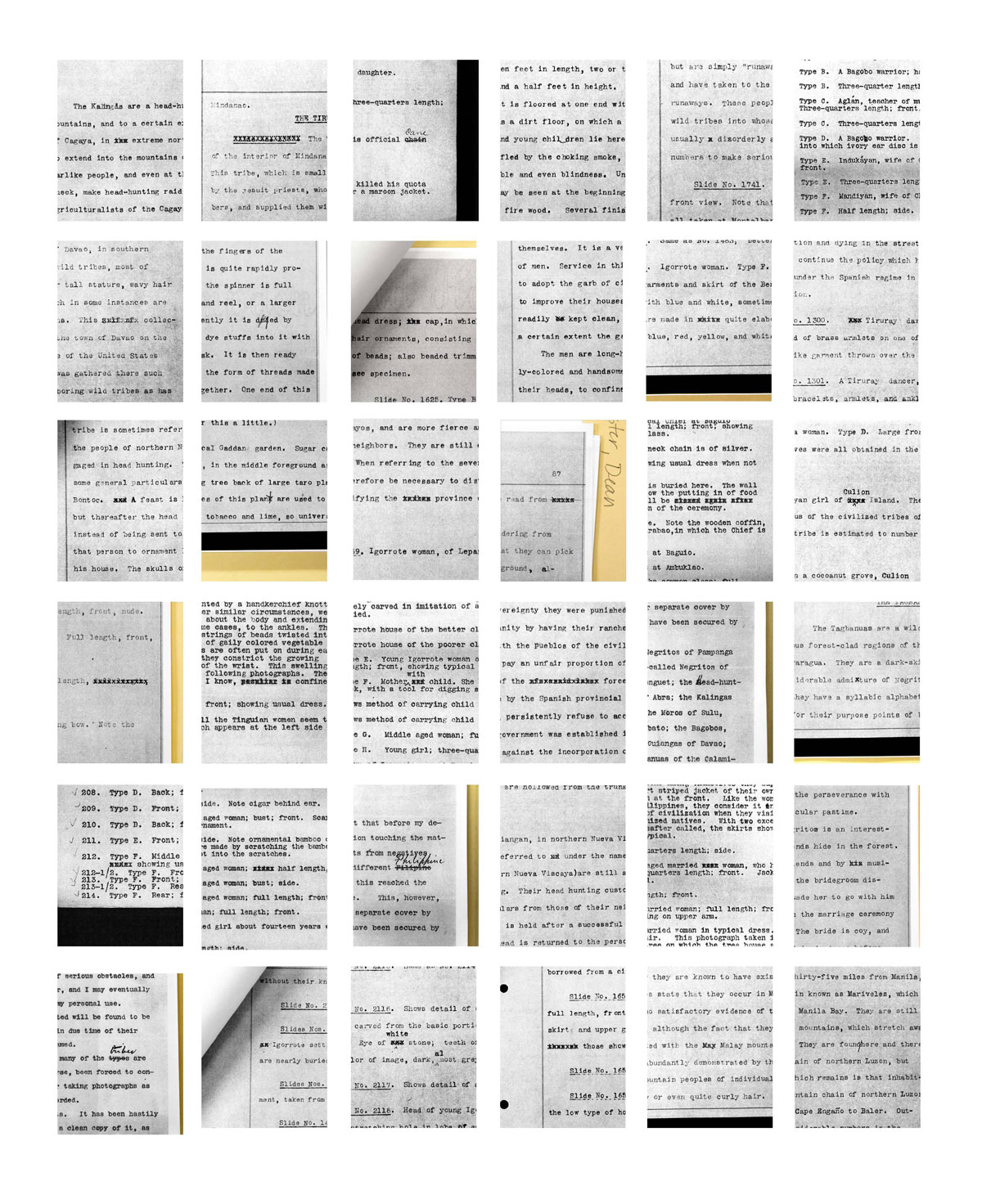

Fixed Focus (Dead Center) is an imposing grid of 36 photographed photocopies of typed archival notes. The original documents were compiled between 1899 and 1913 by the American ethnographic explorer and ardent colonialist Dean Conant Worcester. Syjuco draws our attention to corrections in the texts, suggesting that this and other archives are rife with errors that have significantly influenced how Filipinos (and other colonized populations) are constructed.