One recent Wednesday evening, Kurt Gollhardt and Darren Gallina were preparing to live call a square dance. “Find a spot on the floor in your living room, in your RV; maybe you’re on your back porch,” Gallina said, guiding participants into formation. Despite being physically distanced, the dancers were still in squares—on Zoom, that is. “Allemande left, then do-si-do walking back to back with your partner,” Gallina instructed as more than a dozen dancers began to twirl in their separate spaces.

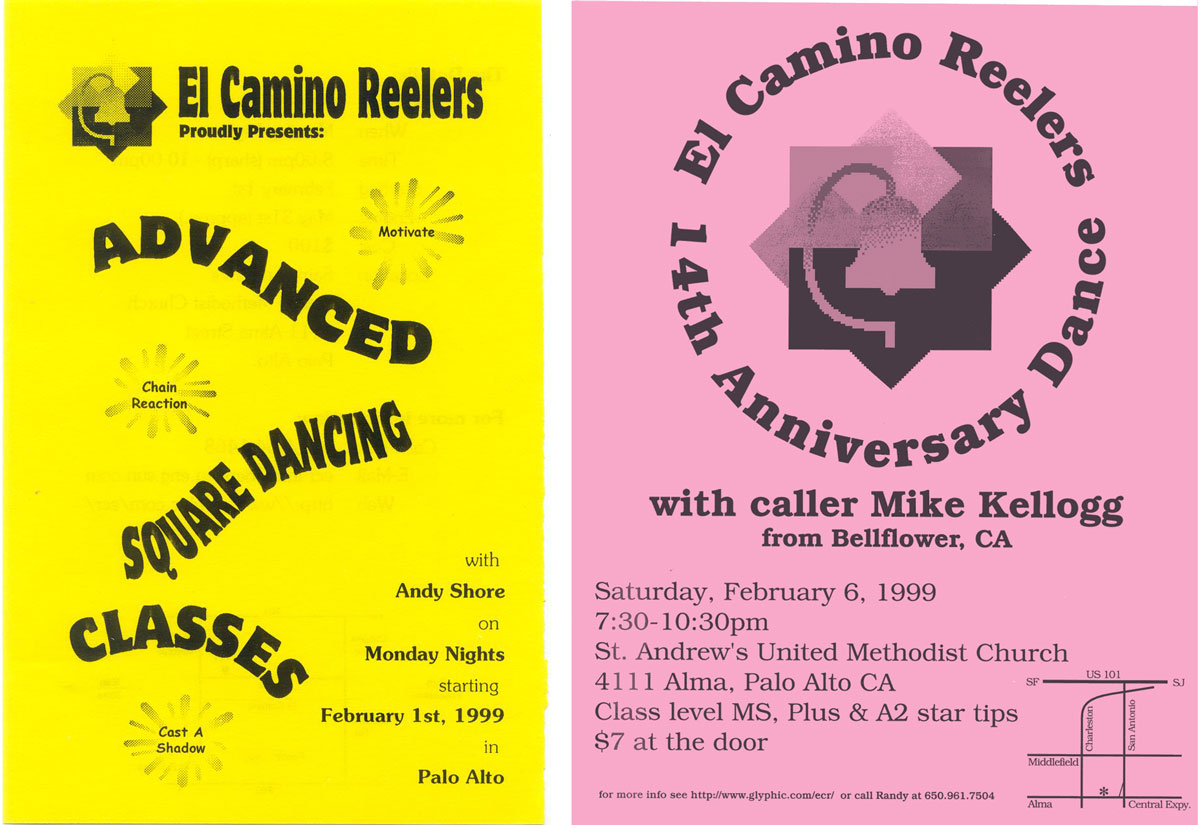

Virtual square dancing is one way Sunnyvale-based Gollhardt has maintained connection this past year with fellow members of the LGBTQ+ square dancing club the El Camino Reelers. While adhering to public health guidelines over the past year has lead Bay Area residents to more obvious adaptations—distanced activities like paddling clubs and outdoor performances—the delightful pursuit of square dancing stands out as an activity that pairs Bay Area values of gentle, geeky fun with LGBTQ+ pride.

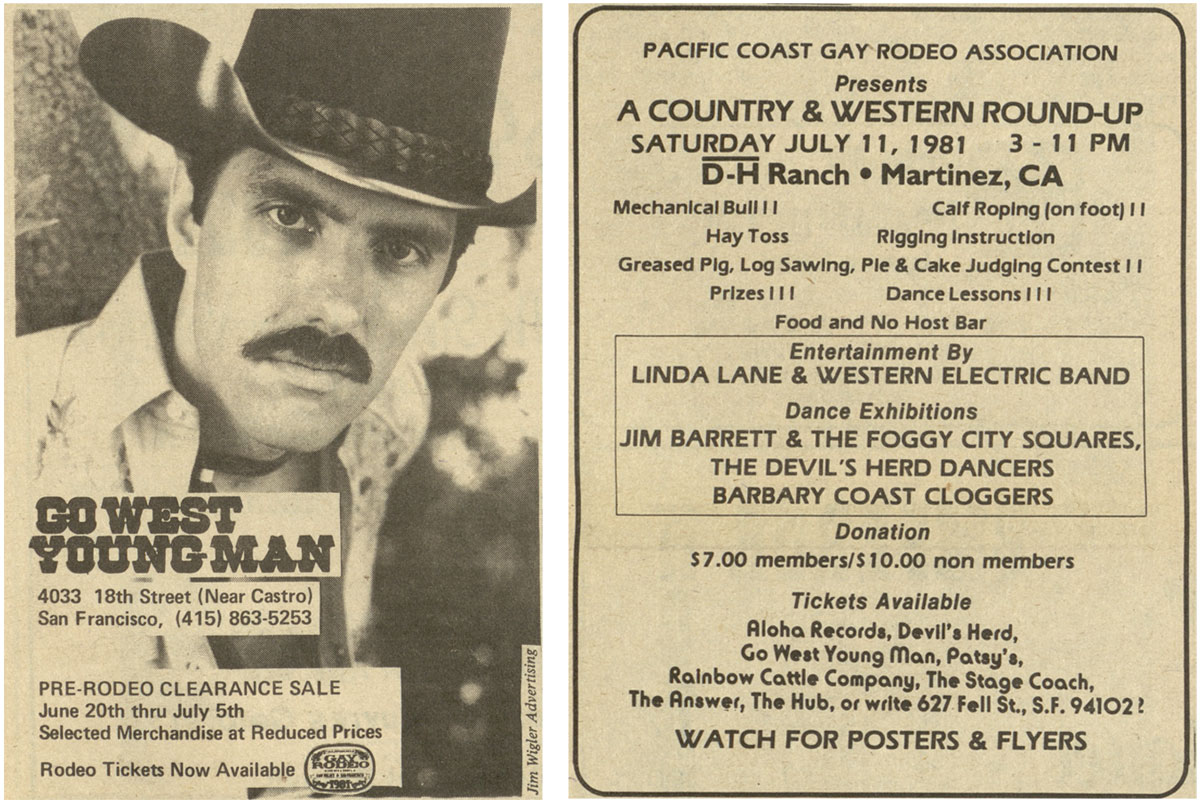

Some of the region’s largest and most active LGBTQ+ square dancing clubs also have roots in another devastating health crisis, dating back to the early years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, when nationwide, these recreational clubs served as a low-contact social outlet, often flirty but dependably non-sexual. Today, these havens of safe, unselfconscious socializing are hoping a pandemic-fueled interest in trying new things will draw open-minded newcomers to this storied pastime.

Square One

If you’ve never seen it, square dancing is exactly what it sounds like: four couples dancing in patterns across an invisible square grid. Beyond that basic premise, there’s plenty of room for improvisation by callers who direct the dance moves in real time, as well as varied music genres and tempo.

Though many will now associate it with elementary school gym class, the eight-person dance style dates back centuries, with roots in European folk dancing, as well as often-overlooked origins in Native American and African practices.