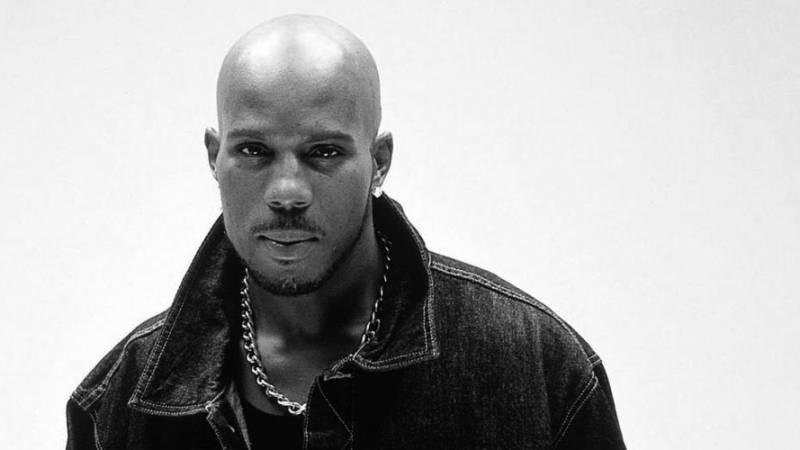

DMX gave us vivid stories about lives we didn’t live, and became the rapper we all had a crush on. I remember listening to “How’s It Goin Down” as a teenager and being swept into a world of lost love. This song unfolded like a movie to me, right down to the specific description: “Coming through, like I do, you know, getting my bark on / Knew she was a thug ‘cause when I met her she had a scarf on / 54-11, size 7 in girls / Babyface, would look like she was 11 with curls / Girlfriend (what!) remember me, from way back, I’m the same cat / With the wave cap, the motherfucker that TNT used to blaze at.” I was sad that DMX and this woman couldn’t be together. Faith Evans’ soft vocals during the chorus made this sense of yearning palpable and real.

Through his music, DMX made it okay to own our emotions, to wrestle with them, to feel, and to heal, openly, without fear of shame or judgement. He was vulnerable in a way that we were taught not to be, and that’s where he connected with so many. I saw my black and brown classmates fighting to hold back tears after being clowned and dissed, after losing or winning physical fights, or coming to school after traumatic home experiences in pain, only to feign happiness, to smile as if things were okay. Black boys were encouraged to adopt a tough masculine persona that erased the texture of their emotions, and the toxicity of that kind of existence only damaged their lives further, as they adopted troubling patterns of exerting dominance over others in unhealthy ways.

But something in DMX’s music—in his own admissions of pain, trauma, flaws, and joy; in the way he played with pitch and tone in his vocal delivery, the way his voice could go from a low rasp to a heightened hymn; in the way he could carry a whole song—gave us another way to see the complexities and contradictions of life. On “Slippin’,” when he rapped “Damn, was it my fault, somethin’ I did / To make a father leave his first kid at 7 doin’ my first bid?,” I felt the pain of his abandonment, but also a sense of unyielding hope.

DMX often prayed onstage, and when he cried onstage during a prayer, it radiated strength and a kind of transparent, elevated spirituality that most hadn’t achieved yet. He was not interested in hiding, or showing only parts of himself. He was a whole, complete person and artist and this is how we remember him.

DMX expanded the emotional depth of his art form. As artists, may we all strive to do the same.

Nijla Mu’min is an award-winning writer and filmmaker raised in Oakland. Her feature film ‘Jinn’ premiered in 2018, and she has since directed episodes of ‘Insecure’ and ‘Queen Sugar’ for television. Learn more here.