The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art show Close to Home: Creativity in Crisis was meant to open in December 2020. The exhibition would have been one of the first in-person examinations of how local artists responded to, adapted to and coped with the COVID-19 pandemic, the shelter-in-place orders, and the 2020 protests against anti-Black racism in policing. But characteristic of a year of whiplash to which the seven artists were reacting, the exhibition was pushed into spring 2021 when the museum, briefly open in the fall, shut its doors once again.

Though the pandemic was far from over when Close to Home was first announced, there had been talk of a turning point. In this way, the exhibition concept originally carried a sense of looking back. But the ongoing pandemic has erased the feeling of separation from the subject matter. Now open, Close to Home is peculiar; it feels like it is historicizing a moment from the past while we are very clearly still living in that moment.

Throughout the past 15 months people have remarked on the confounding sense of time created by the pandemic. There seems to be no rhyme or reason as to what feels recent and what feels long gone. The relationship between time and memory—its importance but also its occasional elusiveness—is evoked by James Gouldthorpe’s COVID Artifacts series (2020–21), installed as a grid of 88 small paintings. These visual snapshots include images of a woman singing from her window during shelter in place; a toppled statue; Christian Cooper, the Black birdwatcher falsely reported to the police in Central Park; a can of Goya beans; an air tanker fighting wildfires; and many scenes of doctors, hospitals and funerals.

There is something exhausting about reviewing this record of the year and realizing certain events happened less than 12 months ago. Yet it is also reassuring to take in the year this way. It is a reminder that the exhaustion many of us feel is well grounded.

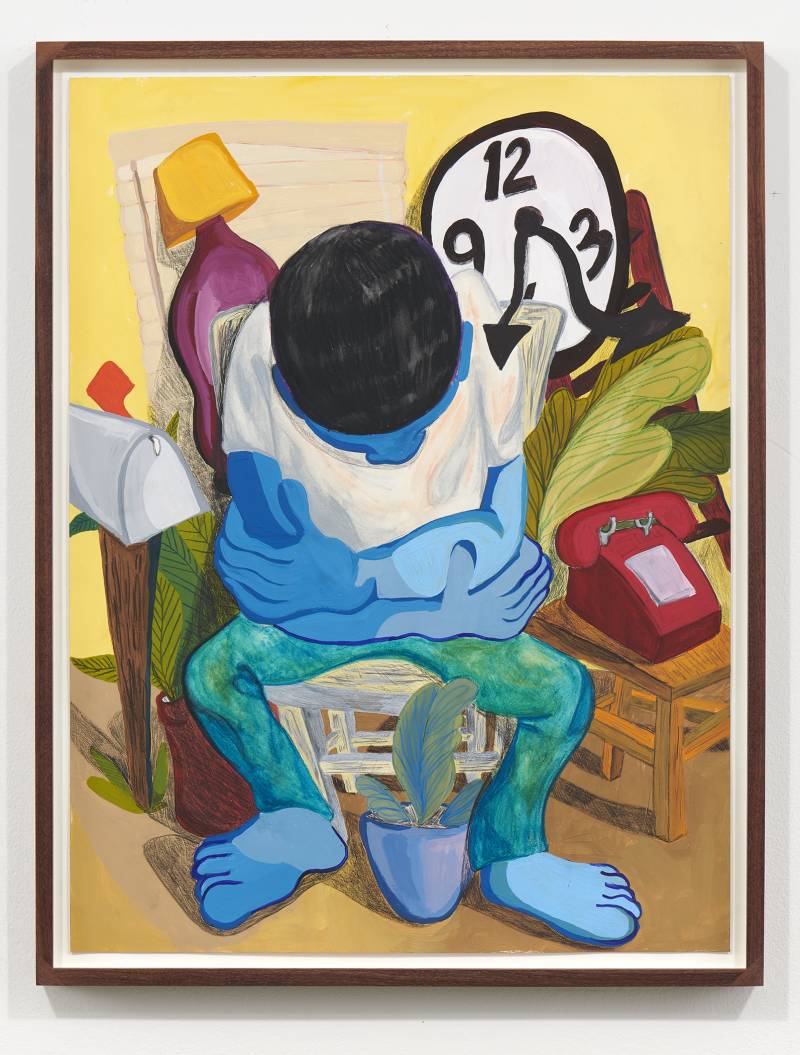

Other emotions associated with the pandemic are seen in Woody De Othello’s self-portraits on paper, created at the beginning of shelter in place while he was stranded at a residency in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Exhibiting the cartoon-like plasticity for which his ceramic work is known, these paintings dramatize the feelings of isolation and loneliness, likely recognized by most viewers even if their individual situations differ. Definitely a Mood (2020) could be a portrait of shelter in place, with a blue De Othello (physically and emotionally) cradling himself in his arms while gazing at the ground. The mailbox and telephone that flank him are reminders of the yearning for connection, and a clock with wavy unreadable arms is a marker of the disorientation of pandemic time.

De Othello explains that making these paintings was crucial to his mental well-being, and this is a common theme throughout the artists in the exhibition. For example, Klea McKenna’s No Feeling is Final (2020) began, she says, as a way to stay sane and to make a living at home without access to the materials and facilities she normally relies upon. Using handkerchiefs (to her, symbols of compassion), watercolor ink and the sun, McKenna created a series of colorful camera-less photograms that are installed in a 140-piece grid on one wall. On an adjacent wall, the handkerchiefs themselves are dyed black and hung more freely. The installation recalls the kinds of rituals many of us partook in during shelter in place—to make sense of what we were experiencing, to mark time, and to ground ourselves in a world of uncertainty.

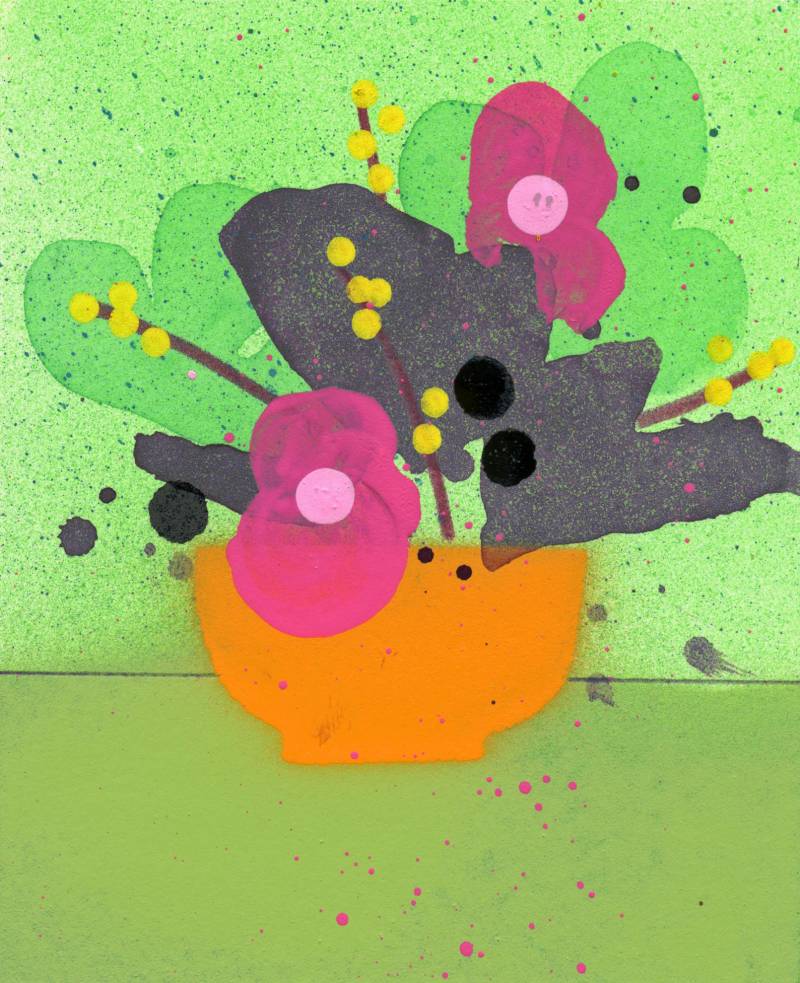

It makes sense, then, that multiples and repetitions are common in Close to Home. Tucker Nichols contributes a series of small paintings to the show, Flowers for Sick People (2020–21), part of a larger project the artist undertook to ease isolation and forge new connections. Nichols created a website where people can request small paintings of flowers for those experiencing illness, later expanding the work beyond its original private confines by posting paintings for groups he imagined warranted flowers.