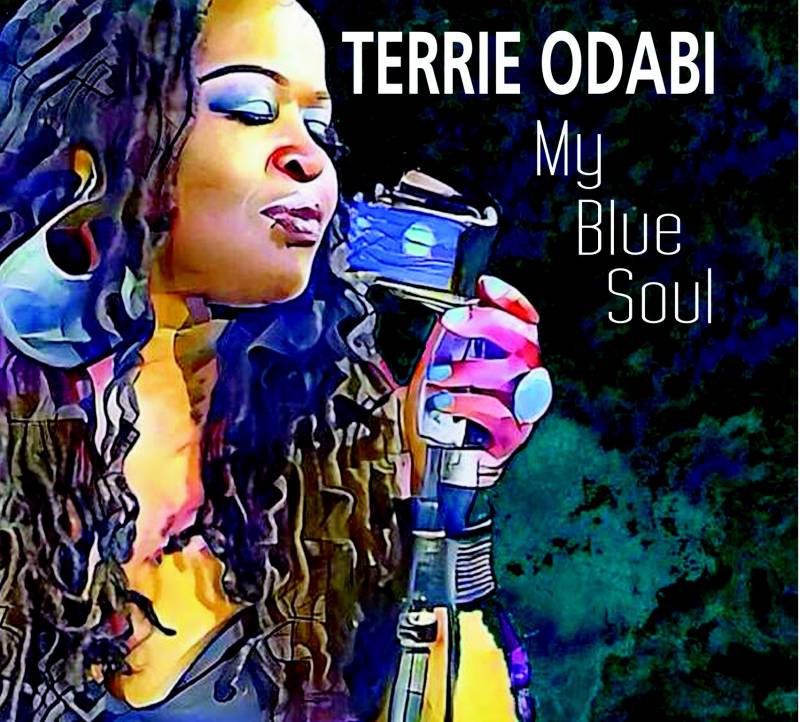

It’s not that Terrie Odabi doesn’t appreciate her nomination for best soul blues female artist in the 42nd annual Blues Music Awards. The Oakland vocalist loves standing in contention alongside the formidable women who helped pave the way for her, including Bettye LaVette and Dorothy Moore.

But when the Memphis-based Blues Music Foundation presents its virtual awards ceremony on June 6, Odabi will keep her focus on a bigger picture. Since the advent of the pandemic, with no gigs or even rehearsals on the horizon, she’s been gathering online weekly with a cadre of women blues artists to talk about the state of the industry. And like much of the country is starting to confront racist legacies in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Odabi and her peers are pushing for a blues reckoning.

Often overlooked by labels, under-booked by clubs and marginalized by American blues festivals, “Black women find it very difficult to make any headway in the blues scene,” she said. “It’s not a billion dollar industry, but you can make a living. We wanted to do something to try to change it rather than complaining.”

The women have organized around the petition “Artists, fans, allies for equity and equality in the blues,” written by Toronto blues artist Shakura S’Aida and Annika Chambers, a rising blues star from Houston who’s also up for a Blues Music Award in the same category as Odabi. With some 1,300 signatures so far, the petition outlines the music’s deep and abiding roots in African American culture while detailing a series of steps that would help level the playing field for Black women on the blues scene.

It’s a broad and deep agenda, covering the history of exploitative recording contracts and non-payment of royalties, the need for blues-centric music education in grade school, and the importance of allyship. In a plea to non-Black colleagues, the petition encourages them to speak out and stand up for Black artists, especially when they see them excluded from lineups. “Labels, agencies, promoters, managers, DJ’s and distributors must make it a priority to ensure that they are representing an equal percentage of Black musicians on their rosters,” the petition reads.

If it sounds counterintuitive that Black women are marginalized on the blues scene, Odabi and Chambers both describe numerous conversations with festival promoters who’ve told them there’s no need to book another Black woman because they’ve already got one on the program.

“The blues has been hijacked,” Odabi said. “Promoters are quick to tell you that blues is not Black, and it’s not unusual for them to book an all-white blues festival. They glorify the blues artists who are dead, but living Black blues artists get no love.”

They’ve focused a good deal of their attention on the Blues Foundation because of its central role in telling the music’s story to the general public and promoting blues artists. After decades of avoiding politics, the organization has taken more forthright stances in recent years, most visibly in March when it rescinded Kenny Wayne Shepherd’s nomination for blues rock artist of the year in response to his use of Confederate flag imagery. (Shepherd responded to the Blues Foundation with a statement that said, “I condemn and stand in complete opposition to all forms of racism and oppression and always have.”)