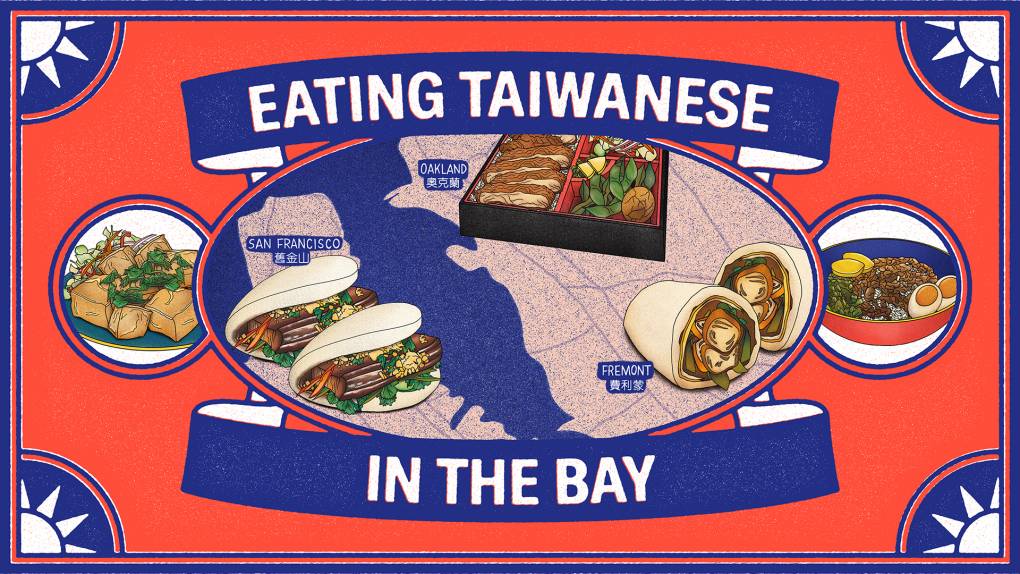

KQED’s Eating Taiwanese in the Bay is a series of stories exploring Taiwanese food culture in all of its glorious, delicious complexity.

I

grew up as the daughter of Taiwanese immigrants—first in San Jose, and later in a South Bay suburb clocked as having only a 5.1% Asian population in 1990, when I was in elementary school. Other Asian American students were rare, and Taiwanese American students were even rarer; there were no Taiwanese American kids in my day-to-day life, as far as I knew.

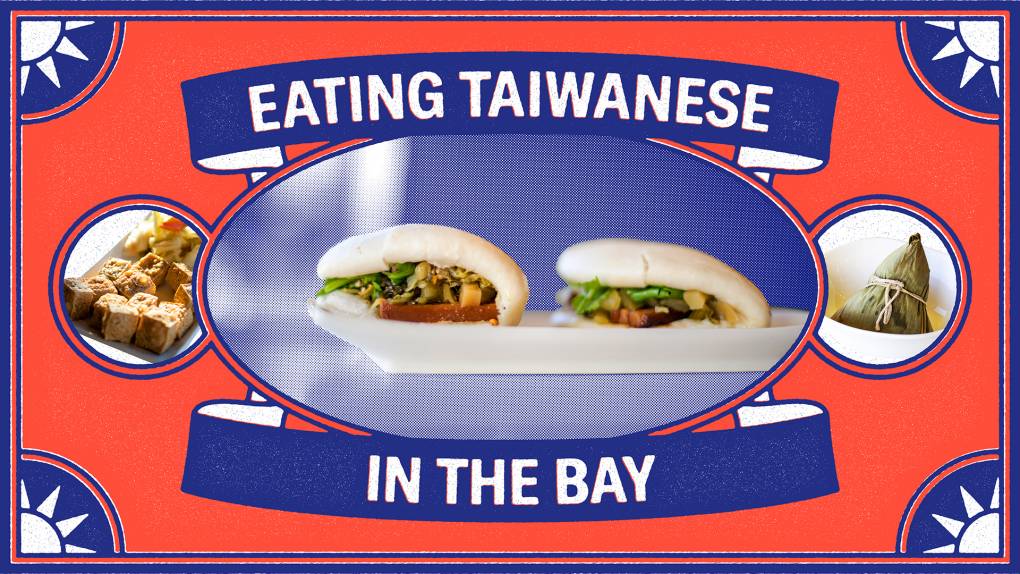

Taiwanese cuisine, on the other hand, remained a large part of my childhood. At home I ate light meals of vegetables and fish, with little oil, cooked by my mother. On weekends, my family went to Marina Foods or Ranch 99 for groceries after lunch at Cupertino Village, a mostly Asian shopping and restaurant center where we’d feast on soup dumplings and beef noodle soup, leaf-wrapped zhongzi and spicy string beans limp on the plate. At the end of every meal, we’d go to a boba tea cafe called Fantasia for thick, buttered toast and boba. Even back then, before boba had been widely recognized by the non-Taiwanese palate, the place was already popular among high school students.

These days, as a San Francisco resident, I am sometimes asked about where to best enjoy Chinese food in the city, and my answer is usually a verbal shrug. Whereas San Francisco’s famous Chinatown is historically working-class Cantonese, most Taiwanese immigrants to the Bay Area ended up in places like Cupertino, Milpitas, Foster City and Fremont, which is why so many of the region’s Taiwanese restaurants opened there. After I moved to San Francisco, my consumption of Chinese food dropped dramatically—to say nothing of Taiwanese food, which became nonexistent. Approximately a decade had passed since I’d lived in the South Bay, and I didn’t know where to find the dishes that I had grown up eating; visiting Cupertino was no longer a regular part of my schedule. In San Francisco, I was even confused about where to find the Taiwanese grocery brands with which I was so familiar, and relied on my brother and his wife for deliveries of Bull Head barbecue sauce and pink net–wrapped packages of made-in-Taiwan rice noodles.

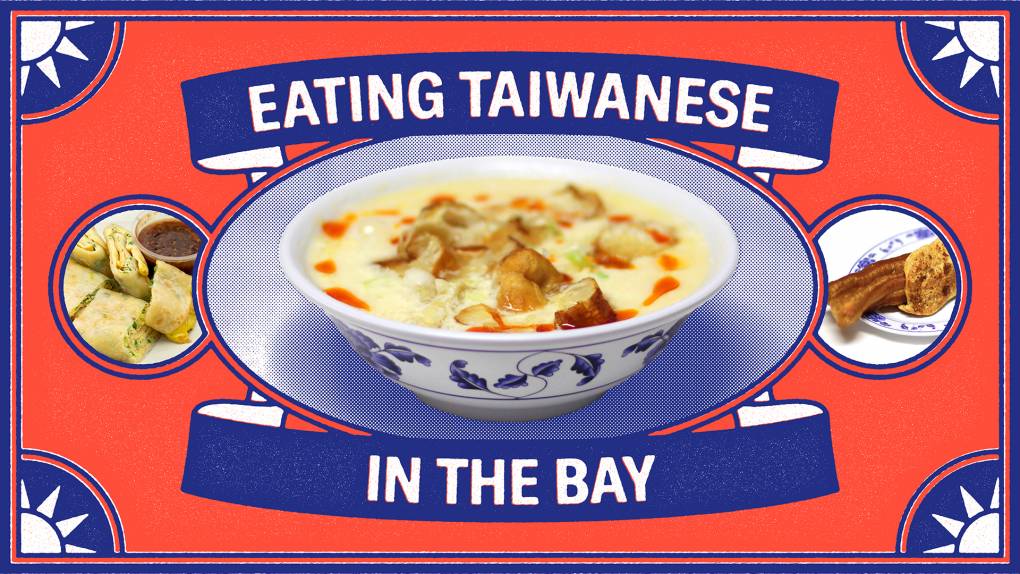

Near the beginning of the pandemic, a friend sent me a link to Liang’s Village, a Cupertino-based Taiwanese restaurant that had newly begun advertising Bay Area-wide delivery ever since it halted dine-in service during lockdown. I was delighted to find that their menu offered so many familiar dishes: preserved egg and tofu with pork sung and scallions, fried pork chop rice, beef and tendon noodle soup, and black bean with pork and bean curd noodles. These were dishes that my mother had made at home, or that I’d eaten during those weekend excursions to Cupertino.

Over time, I began to order from Liang’s Village on a regular basis, rediscovering my favorites easily as the restaurant dropped large boxes of food on my doorstep. I’ve ordered four or five servings of the stewed tofu with oyster sauce at a time, enjoying the silken tofu wrapped in a wrinkled bean curd skin anytime I felt like it. When the package of Pingtung cold noodles arrived at my door—called “Cold Peanut Noodle” on the Liang’s Village menu—I dumped the entire mixture of slippery noodles, peanut-sesame sauce and julienned cucumbers into a bowl, which I gleefully enjoyed in bed.