In Oakland, a city that is historically Black and grounded in the experiences of Black people, a future without Black people seems hard to believe. Yet often, when visions of the future are presented in media, Black people seem to have suddenly disappeared from that existence. So the very insistence that there are Black people in the future, as Alisha Wormsley proclaimed in a 2017 artwork, becomes radical, and a perfect departure point for the Oakland Museum of California’s newest exhibition, Mothership: Voyage into Afrofuturism.

Initially meant to open in October of 2020, Mothership was organized by OMCA curator Rhonda Pagnozzi in consultation with Los Angeles independent curator Essence Harden and former OMCA senior curator of art René De Guzman. Throughout, the exhibition stresses the importance of centering the voices of Black creators illustrating Black experiences.

Walking into the exhibit, visitors first enter a room entitled “Dawn,” dedicated to Black feminism and showing how Afrofuturism, science, magic and the divine feminine are all connected. There, Sydney Cain’s mural Radio Imagination depicts concepts of Black ancestral healing techniques through images of astronomy and Black femininity. It’s accompanied by Nicole Mitchell’s soundscape Mothership Calling, which mimics the voyage enslaved people took to this land through the sounds of trains and a conductor saying, “All aboard! Come on down.” Together, the works are mesmerizing; visitors hear the sounds of a harp while looking at images depicting the creation of life.

“Afrofuturism can be a great vehicle to envision Black liberation and hope,” Mitchell says in the nearby wall text. “Mothership Calling collides joyful sounds with mystery in a sonic expression of gentleness, representing fragments of Black life, in an effort to bring healing and wonder.”

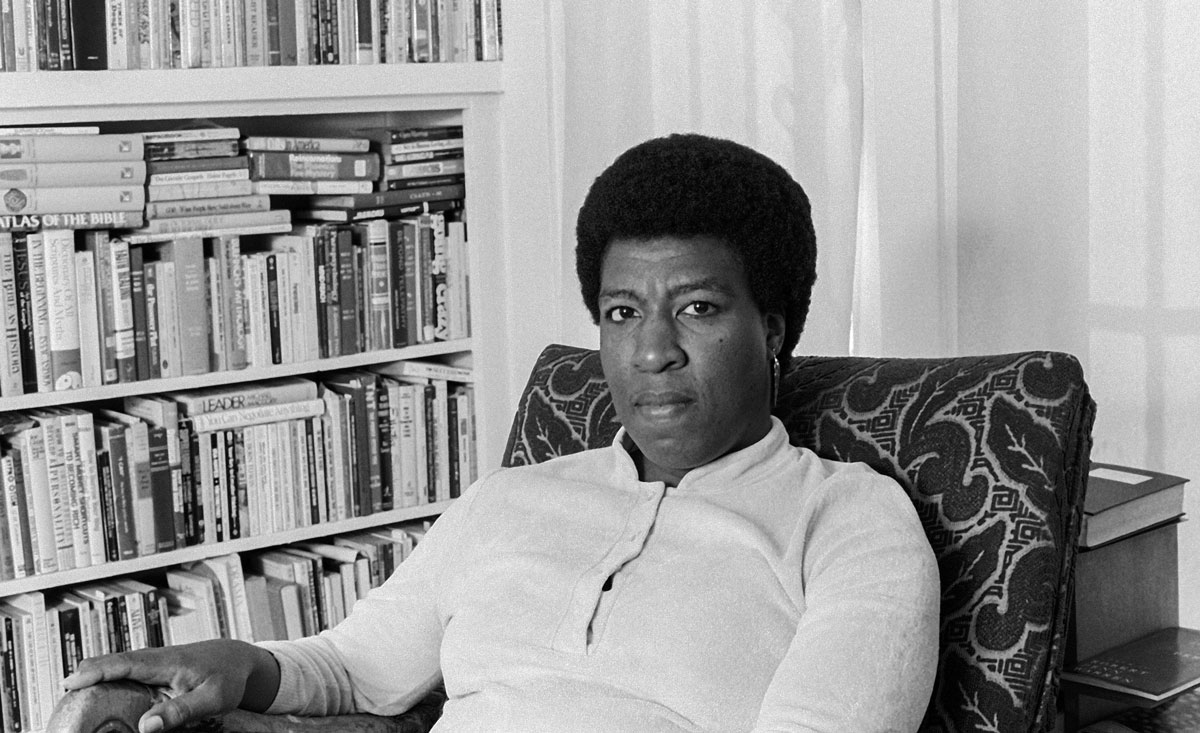

Further into the concept of “Dawn,” best-selling science fiction author Octavia Butler’s books and handwritten notes demonstrate the intersectionality between Afrofuturism and feminism. (“Dawn” is not only the start of the Mothership, it is also the title of one of Butler’s novels—one that depicts a Black woman in a post-apocalyptic world.)

On the opposing wall, visitors can see how science plays a role in Afrofuturism with the mere existence of Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells were taken without her knowledge or consent, and were found to reproduce indefinitely. Since 1951, HeLa cells (as they are called) have been incredibly important to medical research, including the development of the polio vaccine. They have even been used to help understand COVID-19.