In 1979, literary critic Michiko Kakutani proclaimed “California belongs to Joan Didion.” The writer—who grew up in Sacramento—shot to fame in the late ’60s and spent her illustrious writing career enchanting readers with her observations of the Golden State, the mercurialness of the Santa Ana winds, and the lives of hippies in Haight-Ashbury. She did this in her quintessentially unsentimental and journalistic prose and, as many have pointed out, from a perch; she lived in a mansion in Brentwood (a tony L.A. enclave favored by celebs like Marilyn Monroe and Joan Crawford) and partied with the Hollywood elite. Her name became synonymous with a certain aesthetic that was later emulated by countless other thin, white, wealthy women. Didion’s legacy looms over California like a long shadow. In recent years many literary voices have argued this as a reason to rethink her canonization as “St. Joan” (as Vanity Fair dubbed her in 2016).

The subheading of writer Myriam Gurba’s recent essay, “It’s Time to Take California Back from Joan Didion,” reads: “The first lady of West Coast letters needs to share that honor with the Mexican diaspora.” The argument Gurba and others present is that her dethroning would give rise to new voices that are more representative of the racial and economic background of the U.S.’s most populous state. One such voice is that of Oakland resident José Vadi.

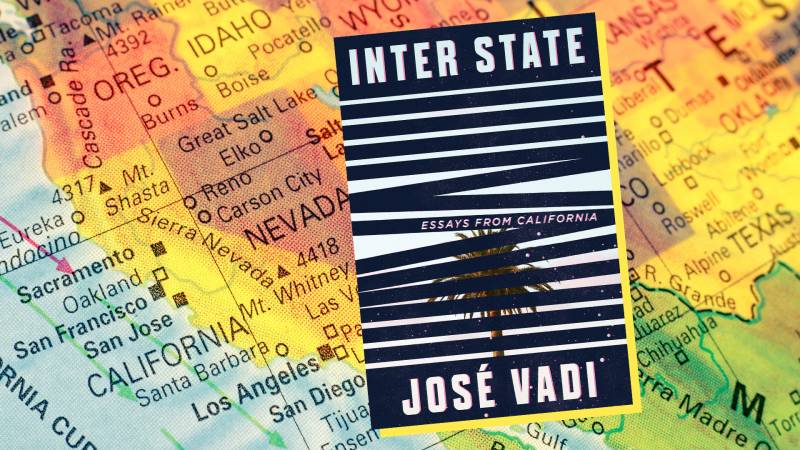

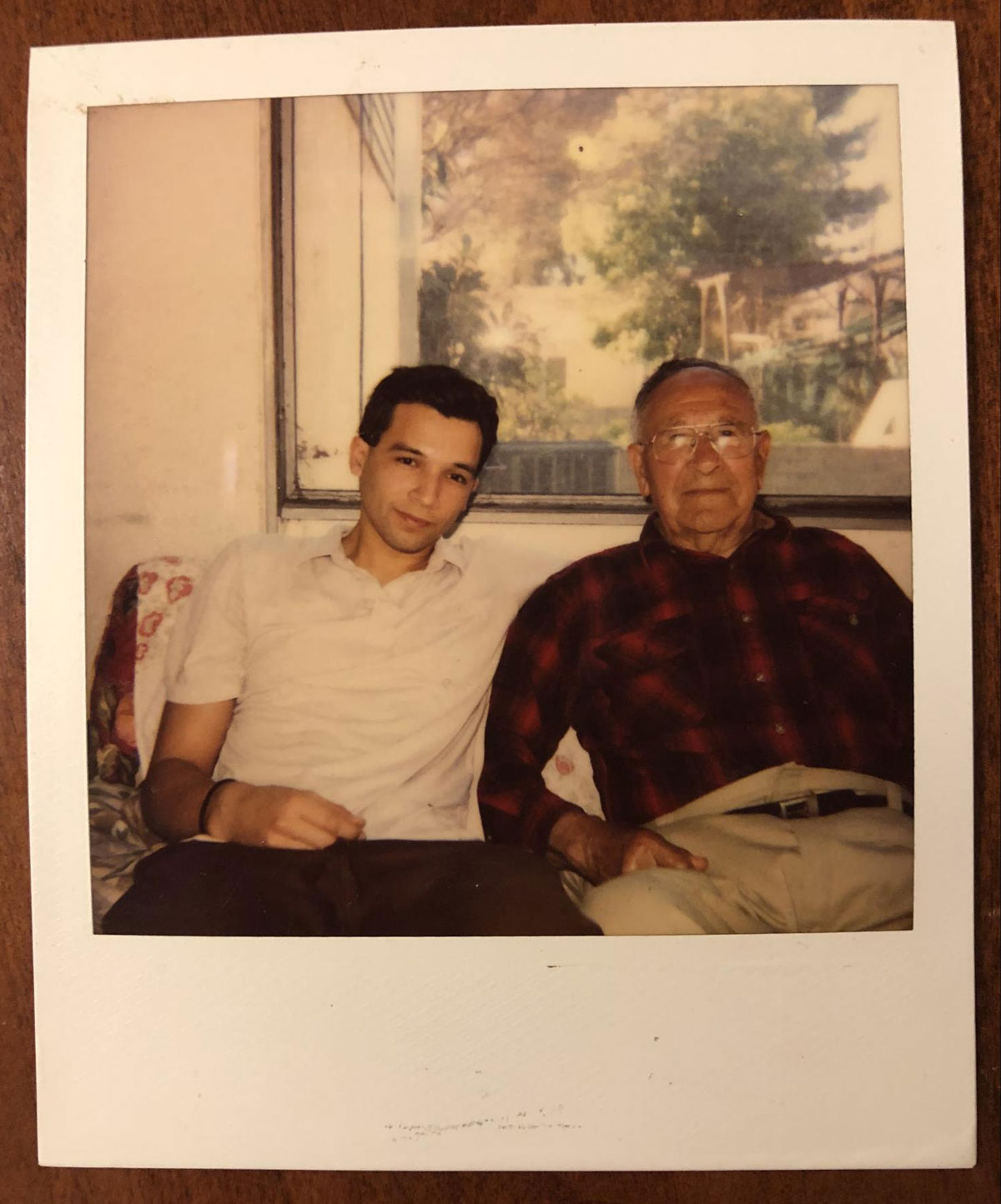

Vadi is the grandson of Mexican farmworkers, a poet, and a lifelong skater. His new book, Inter State: Essays from California reads like salvage ethnography from an amateur anthropologist. “I fear losing California,” he states in one of the book’s seven related essays. That fear propels him to study it, take grainy pictures, and preserve it in the way he knows best: in words. His voice offers earnest narration about gentrification and other changes that he recognizes have the power to turn him into “a modern-day Okie” in his home state.

“The California dream is inherently stratified,” Vadi explains to me. “It’s based on class, and as a result of that, it’s based on race and geography.” Mapping that changing geography is the work of Inter State. In essays like “Standing in the Shadows of Brands,” and “14th and Jackson,” Vadi explores the way the tech industry has altered the landscape of San Francisco. Expansive development projects for luxury housing complexes continue while the homelessness epidemic worsens; the city’s skyline is altered by brands in a way Vadi notes is “akin to SimCity’s logical apocalyptic end.” In an essay titled “California Inquiry,” he writes: “The biggest question facing this state isn’t just its survival but its destruction.”

California is a palimpsest; there are cities and stories that were erased to make room for the ones that exist now. Vadi’s dispatches about gentrification sanitizing Oakland, the state’s many unheralded laborers (like the incarcerated men and women who work shoulder-to-shoulder but not dollar-for-dollar with our firefighters), and the tech and population booms reshaping the state, are an attempt to unearth those stories.

At the root of Vadi’s connection to California is his grandfather who passed away in 2011. “A lot of these essays are answering questions I had about my family’s relationship with the state, and my own,” Vadi explains. The book is a way of honoring his grandfather and the many like him who lived an “under-the-table existence.”