In the billboard-sized photograph that greets visitors at Gallery 16’s entryway, a young Jim Melchert sits astride a large wooden sculpture, leaning forward, his shirt pulled over the top as if impregnated by it. The sculpture is of the lowercase letter “a”; a smaller version of the same letter “a” can be seen on a pedestal in the gallery. Both works were included in Melchert’s 1970 exhibition, a show, at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI); the photograph, taken by fellow artist Bruce Nauman, was used for the announcement poster.

In lieu of any introductory wall text, this photograph marks the onset of the artist’s enduring interest in exploring the variations on a theme, the reacquaintance and rediscovery that, as Melchert notes in the essay by writer Maria Porges for the accompanying exhibition catalog, “I think that’s how our minds work—we keep circling the same issues, but with increasing clarity and depth.”

The exhibition Rethink, Revisit, Reassess, Reenter, on view through Oct. 31, is in essence a mini-retrospective spanning 50 years of the 91-year-old artist’s career. It makes an argument for Melchert’s place in contemporary art history, highlighting the conceptual rigor of his long practice. If we are at this moment in time understandably reluctant to admit one more white male to the canon, the testament for Melchert’s inclusion might be found in the roster of former students’ signatures at the gallery desk, evidence of his highly consequential career spanning decades as a professor at SFAI and UC Berkeley. His tenure at these institutions was interspersed with roles as the director of the Visual Art Program for the National Endowment for the Arts and at the American Academy of Rome. In sum, Melchert’s practice as an artist is inextricable from the agency that he created for other artists.

The earliest works on view date to 1970; the most recent were made a month ago. Included are two early filmed performances, Changes, Amsterdam (1972) and Untitled (The Water Film) (1973). Installed opposite each other, they are variations on themes of fluidity and slowness. In Changes, participants submerge their heads in a large container of slip (clay in liquid form), their discomfort increasingly apparent as caricature-like vessels harden around their features. The stillness of drips arrested mid-flow around hair and beards and noses is punctuated by the fidgety hands resisting the urge to break free from the entombment.

In The Water Film, by contrast, two drenched, nude figures pirouette in a looping slow-motion pas de deux, hurling buckets of water at each other. They leap, combative and ebuillant, as the arcs of water form a visible circumference around them. In both works, the sensual beauty of liquid flowing across bodies conflicts with the violence that erupts or solidifies as it meets them.

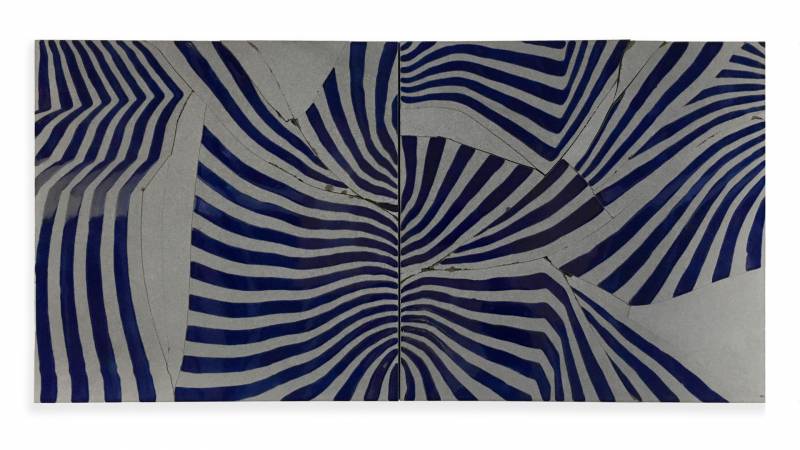

This conceptual framework, in which there is a juncture where things break instead of bend and the rupture is irrevocable, extends to the ceramic works that dominate the exhibition. For decades, Melchert has used commercial tiles that he has broken, glazed, and re-assembled into reliefs and grids. The cracks and fissures flow across the linear compositions, the glazed striations or dots pulling attention to where the fractures have occurred. The breaks reveal the invisible, individual weaknesses in the bonds of the apparent uniformity of these fabricated tiles. It is a drawing practice in clay. In the same way that a mark alters the surface on which it is made, these cracks speak to their own making irreducible from their material.