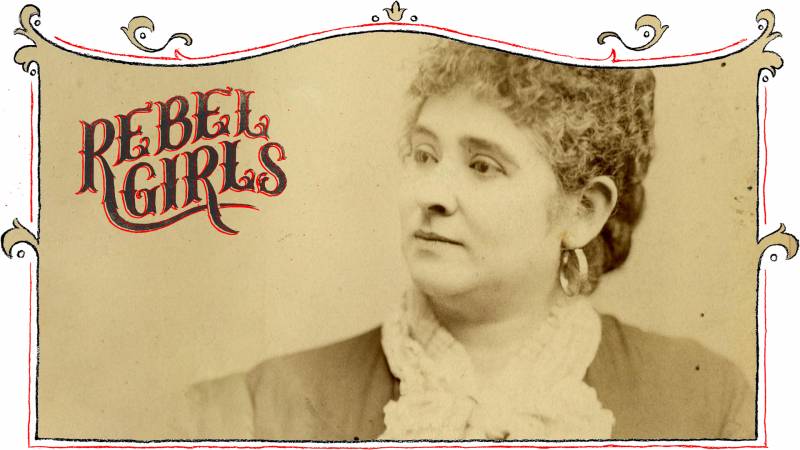

When Hipolita Orendain de Medina first arrived in San Francisco as a young child, it was the result of a bold move by her mother, Francisca Tejada de Orendain. Francisca made the decision to leave Mexico and head to San Francisco in the 1850s, after the death of her husband. The widow and her two children, Hipolita and Virginia, would be among the first wave of Mexican families to emigrate to California following the Mexican-American War, a conflict that ended when Mexico City fell to U.S. troops on Sept. 14, 1847—the same year Hipolita was born.

The Single Mom Who Preserved Mexican American History in the 1800s

Though tensions remained between the two countries at the time of the Orendains’ move, Francisca had inherited a fortune from her late husband Jesús Orendain’s silver mine, and sought new opportunities in the United States. Though she was moving to still-unruly Gold Rush country, Francisca was determined to raise her young daughters as respected and virtuous women of society. She succeeded. After investing in Oakland waterfront properties and some land on what is now Broadway, Francisca went about making sure Virginia and Hipolita received excellent educations. By adulthood, Hipolita was fluent in at least three languages—English, Spanish and German—and had developed a passion for all things literary.

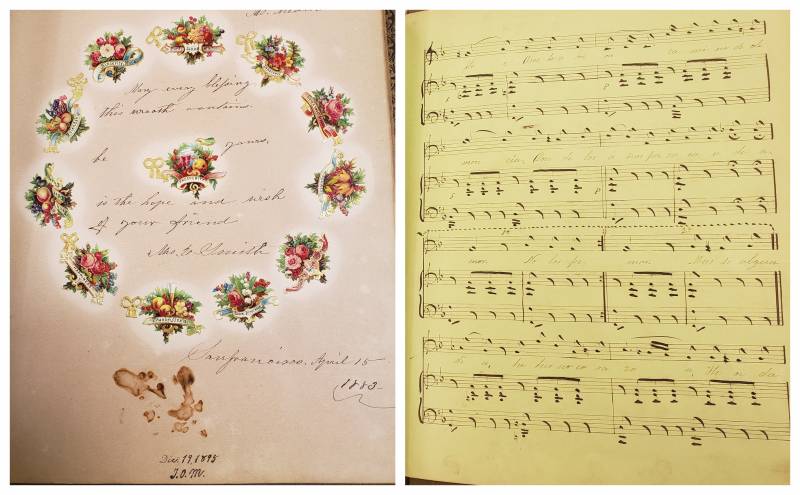

It was her unbridled enthusiasm for the written word that led Hipolita to start keeping meticulous records of her poems, journals and musings. She also filed and stored her “recuerdos de amistad” (tokens of friendship)—the essays, letters, well wishes, portraits and business cards she received from friends and family. Without archival intentions, throughout the course of her life, Hipolita’s personal effects were quietly preserving a vibrant snapshot of Mexican American society in Northern California during the second half of the 1800s and into the early 1900s. One album alone spanned the years between 1865 and 1908.

Some of the letters Hipolita collected offer a glimpse into the hardships and political turmoil felt by the loved ones she left behind in Mexico. One, from M. Travesi, details the chaos and bloodshed of the Second French Intervention in Mexico, a war fought between 1861 and 1867. The note, dated July 14, 1865 begins: “Standing before the arrogance of an infamous and brutal soldiery made up of the vile slaves of the traitor France might offer them liberty? Cowardly executioners! In order to defeat, they raise scaffolding where they assassinate forced martyrs and pure patriots whose noble blood is worn on their faces.”

On March 12, 1867, Hipolita’s cousin Felicio Orendain wrote from Mexico: “Today, we experience much fear while we wait for the result of the battle that at any moment will occur in Querétaro. All the resources of the Republicans against those of Maximiliano [the Archduke of Austria, installed in Mexico by the French government] are meant to create a federal army along with the help of the towns’ resources. In this context, it is very difficult for us (to live here) and, if this commotion persists, our general ruin will be a certain fact.”

Both Hipolita and her mother were actively contributing to the war effort from San Francisco. Hipolita was a member of San Francisco’s junta patriótica (patriotic assembly). She was also active in recruiting men in California to go and fight for their home country. (Words she jotted down in her private notebook show her to be quite persuasive in this regard. “If we have the courage to sacrifice everything to duty,” she wrote, “this sacrifice makes room for the most pleasant satisfaction one can taste.”) Francisca used her wealth to outfit the new soldiers and finance their travel to the Mexican frontlines.

When President Benito Juárez finally regained control of the country, the joy and relief was palpable in letters sent to Hipolita. But much of the correspondence she received is best described as declarations of adoration. Many men seem to have been quite besotted with her. On Sept. 27, 1865, José Montesinol wrote, “What is it about your look, what is it about your smile, that attracts so many hearts? What magic and enchanting qualities does your breath have that awakens soldiers, wounded by deception and their abandonment of love for glory?”

Just three weeks prior to Montesinol’s letter, another suitor named Lozano wrote to her: “Polita, you are the ideal woman, because you are just as virtuous as you are beautiful.” Hipolita no doubt would have seen this as a high compliment, given that in her personal musings she once wrote, “Perfect happiness derives only from virtue.” On another occasion, she noted, “Every time one does not fulfill one’s moral duty, one does not fulfill [one’s] other [duties] either.”

In October 1868, Hipolita married Emigdio “Emilio” Medina at Old St. Mary’s Church, on the corner of California and Grant in San Francisco. Archbishop Joseph Alemany performed the Roman Catholic ceremony, while Virginia acted as a witness. Once married, the couple settled into a family home at 707½ McAllister St. As with her other suitors, Medina was spellbound by Hipolita. In her album of remembrance, she saved the love notes and songs he wrote for her.

Despite promising beginnings, theirs was not a relationship that would last. Medina was a diplomat who traveled across Europe and South America on behalf of President Juárez to shore up Mexico’s relations overseas. And together, Hipolita and Medina brought four daughters into the world: Josefina in 1869, Virginia in 1871, Czarina in 1873, and Mercedes (nicknamed Mercy) in 1876. By the 1880 census, however, Medina was no longer listed as a resident in Hipolita’s home despite the fact that he was still an active member of San Francisco society. (In 1881, he co-founded and became editor for La Republica, a weekly Spanish-language newspaper in San Francisco.) Hipolita started referring to herself as a widow long before Medina moved to Los Angeles to edit El Estandarte Mexicano, a publication that was, according to one of his business cards, “Devoted to the interests of the resident Mexican population.”

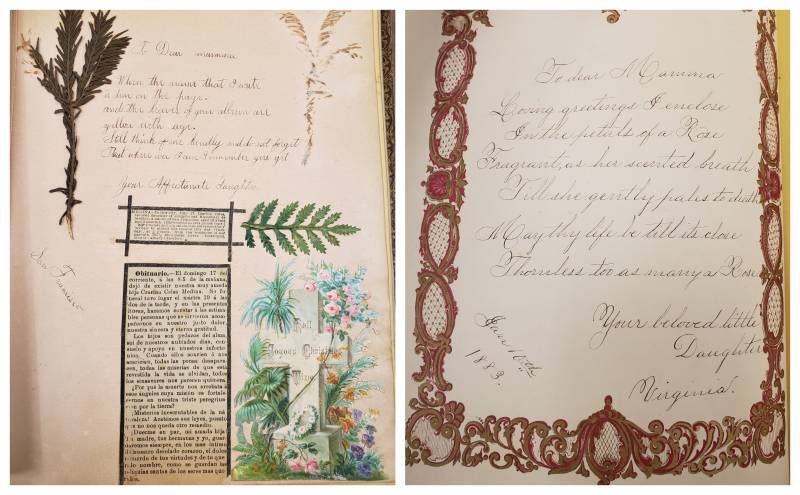

In 1893, Hipolita and Medina came together once more to grieve the loss of their daughter Czarina, who died just three months after her 20th birthday. Hipolita lovingly taped details of her daughter’s memorial from both English and Spanish language newspapers under a passage written by Czarina for her mother. That poem ended with the line, “Wherever I am, I remember you yet.”

As a single mother, Hipolita worked—alongside her sister—as a dressmaker. And she cultivated very close relationships with each and every one of her daughters. In 1894, one friend named Aurora wrote to Hipolita, “You have known with your love and your talent how to form the souls of your daughters with pieces of your heart so that they are the treasure and grace of their home. They have been nurtured by your example in their virtues; virtues that make a woman more esteemed and strong when faced with the trials of life.”

Some of Hipolita’s strength may have been inspired by learning from her own mother’s mistakes. Francisca lost most of her Oakland property investments to squatters, administrators, and the Southern Pacific Railroad. As Francisca prepared to fight the latter in court, threats were made on Hipolita and Virginia’s lives; Francisca retreated and dropped the suit.

Hipolita died in 1922. But her voice, and the voices of her loved ones, live on through her beautifully preserved books and correspondence. Her collection continues to present a vivid snapshot of 19th century life in both the Bay Area and Mexico. That Hipolita understood the value of these kinds of personal papers speaks to an impressive fortitude and degree of self-belief, qualities that continue to inspire new generations—including her own descendents.

In 2016, Hipolita’s great-granddaughter, award-winning author Laurel Anne Hill, dedicated her second novel, 2016’s The Engine Woman’s Light, to her great-grandmother. Hill was also responsible, in 2009, for organizing and funding the translation of Hipolita’s letters and journals into English. Those papers now live alongside Hipolita’s original documents at the California Historical Society. Hipolita’s youngest daughter Mercedes (Hill’s grandmother) may have put it best in a sweet verse she wrote to her mother on Aug. 12, 1883:

You are good as you are fair,

None, none on Earth above you,

As pure in thought as angels are,

To know you is to love you.

To learn about other Rebel Girls from Bay Area History, visit the Rebel Girls homepage.