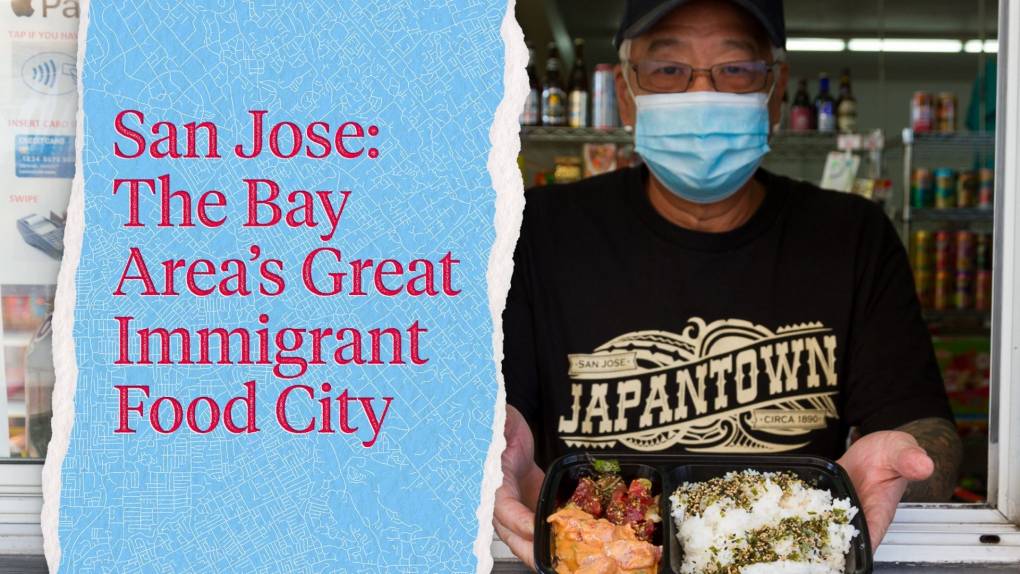

KQED’s San Jose: The Bay Area’s Great Immigrant Food City is a series of stories exploring San Jose’s wonderfully diverse immigrant food scene. A new installment will post each weekday from Oct. 20–29.

I

grew up on the corner of Story and Capitol, the heart of Eastside San Jose. Even back then, nearly three decades ago, San Jose had already developed a reputation as a booming hub of technology and innovation. It was already in the early stages of becoming one of the most expensive cities in the country. My family, undocumented, rented out our apartment’s two bedrooms while the three of us crowded into the living room—a common practice among the low-income families in the community. Everyone just did what they could to make rent.

Most of the other residents in our apartment complex had the same immigration status. We’d migrated from places like Oaxaca, Puebla and Guerrero, in the southern part of Mexico. In our neighborhood, there was a common understanding that if you lived here, it was because of your legal status or your limited resources—probably both. It wasn’t a part of the city for people who had other options.

The early ’90s were particularly difficult for undocumented people in California. In 1994, then-governor Pete Wilson inundated our airwaves with ads for Proposition 187, legislation that prohibited undocumented people from accessing public services such as hospitals or schools. The law was eventually struck down by the courts, but we all heard the talk of how “illegals” should be forced to go back where they came from.

Regardless, with the little we had—and facing a hostile environment—the immigrants in my neighborhood created a community for ourselves. We shared tips on the different ways we were able to get by. We continued to build our lives in this country.

It was around this time that my abuela took it upon herself to start her own informal business. In our neighborhood, this wasn’t an uncommon thing for people to do. For example, the lady in apartment 28 used to babysit kids. The lady in number 14 sold candies, and the one in number 11 sold bottles of soda. This underground economy was what kept our community afloat. Each dollar made a difference.