Although the performing arts have begun to bring back live, in-person performance experiences, it’ll probably be months, even years, before a full recovery in that direction is achieved. Fortunately, many artists have expanded their skills into the digital realm, creating multi-disciplinary and multi-platform works that reach well beyond the fourth wall and right into our living rooms when we need them to.

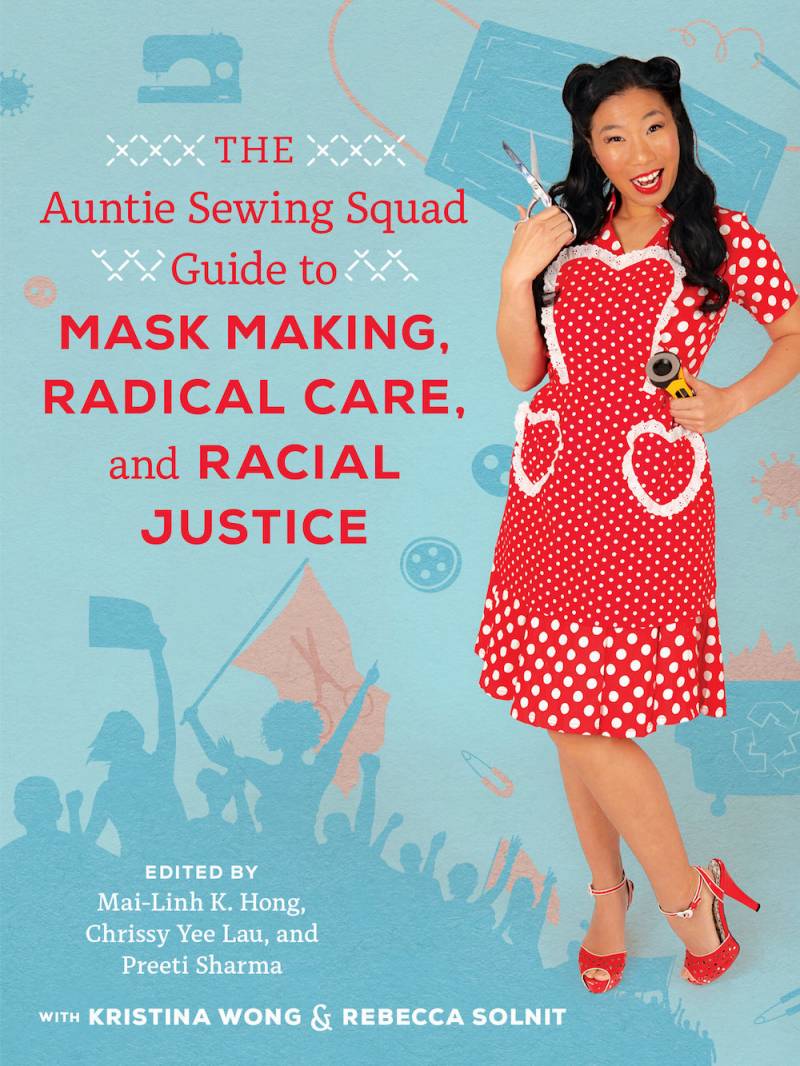

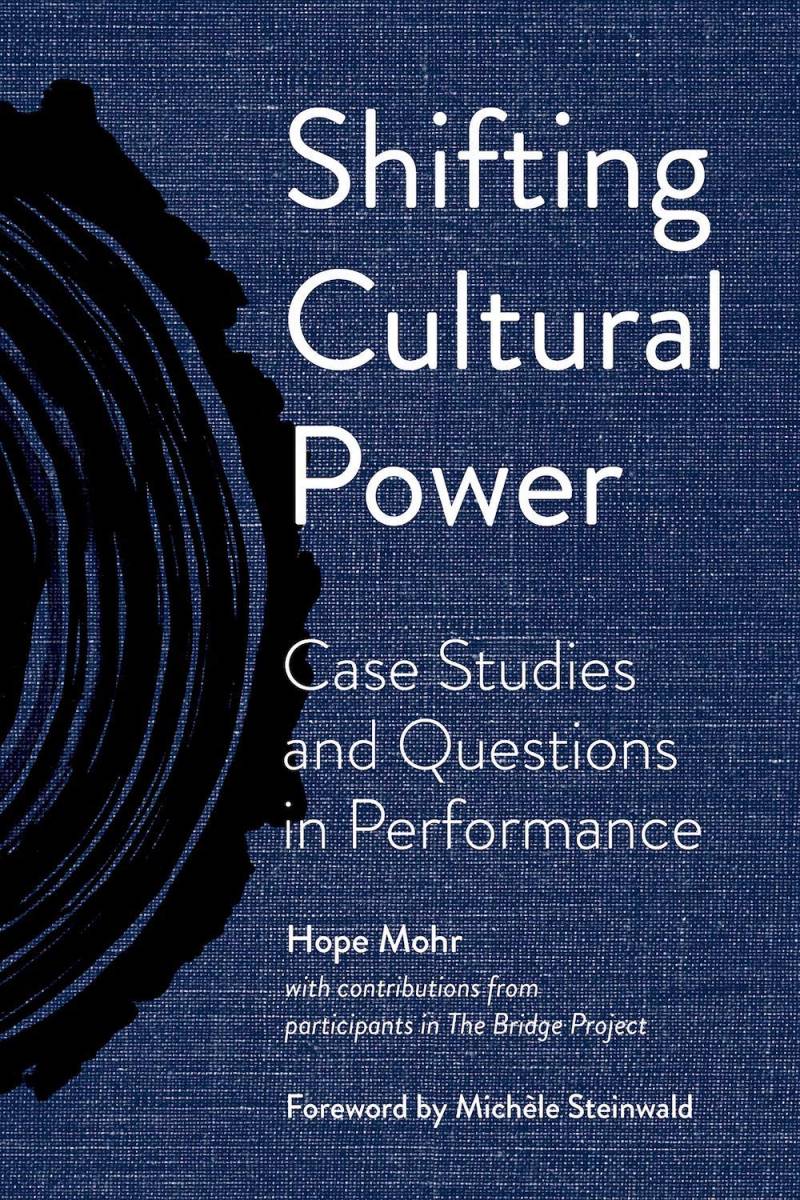

A more analog way to get your theater fix at home is to pick up one of several amazing books by local performing artists published over the past few months. These include Shifting Cultural Power: Case Studies and Questions in Performance, by Hope Mohr; The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice, inspired by and featuring Kristina Wong, and Performing Truth: Works of Radical Memory for Times of Social Amnesia, by L. M. Bogad.

Each of these books addresses the current turbulent moment in the performing arts from multiple angles. Mohr’s book targets arts organizations hoping to create more equitable and transparent governance structures. Wong’s details the emergence of a multi-faceted, long-term pandemic response and mutual aid project, the Auntie Sewing Squad, which harnessed the creative energies of out-of-work artists and others to sew and distribute thousands of masks and PPE to underserved communities. And Bogad’s book offers a variety of road-tested activist artist tactics to create moments of creative protest and inspire radical consciousness.

In Shifting Cultural Power, dance choreographer and performance curator Hope Mohr reflects on the changing landscape of dance, and the ways in which she herself—a white woman steeped in traditions of ballet and postmodern dance—has had to reckon with her own positionality and privilege in the dance community of the now. It’s a frank look at the ways in which a white-led arts organization (such as her own) can transition to a more intentional, diverse, and equitable space, in which leadership roles are shared and curatorial powers become more expansive.

“Curators must make space for artists to step into power,” Mohr writes. “Decentering myself…letting other artists lead…has become my central curatorial commitment.” This artist-led process can manifest itself in different ways, but ultimately, according to Mohr, “for white curators (such as herself), shifting cultural power means curating artists of color in ways that advance the artist, not the presenting organization.”

Like the art of dance, organizational governance can take many shapes and prioritize different methods of engagement and decision-making. Mohr describes the process of shifting her own organization to a co-leadership of three, while also communicating that shift to a wider, interconnected ecosystem of participating artists, audiences, and funders. Throughout the book, she includes multiple voices describing the effect of these intentional shifts on their own artistic and aesthetic processes. Along the way, she documents in print some of the many conversations that are being held in the performance community at large, as legacy organizations grapple with existential questions such as who the work is for and how its development and production can better reflect and support its constituents rather than outmoded organizational structures.