In 1991, one of the most diverse film representations of people living with HIV appeared on the PBS television show POV. Featuring 11 HIV-positive men and women discussing their relationship to and experiences of the virus, San Francisco filmmaker Peter Adair’s Absolutely Positive would go on to win a Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival and an International Documentary Award. But for two people involved in the making of the documentary—Adair and one of his subjects, Doris Butler—it was a milestone of much more personal proportions.

This 1991 Documentary Captured Life With HIV—and the Making of a Powerful Activist

Of Adair’s documentaries, which covered topics as varied as evangelicals and nuclear disarmament, Absolutely Positive was the only film in which he sat before the camera as a subject. The son of anthropologists, Adair and his siblings grew up on a Navajo reservation, where he was an outsider, participant and observer of that world. In Absolutely Positive he once again occupied all these roles for a final time.

The film’s 11 subjects were culled from 120 interviews conducted by Adair, producer Janet Cole and editor Veronica Selver. Similar to Adair’s 1977 film, the groundbreaking Word is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives, it alternates compelling talking-head interviews with footage of the subjects’ everyday lives. Adair narrates the documentary as he did in The A.I.D.S. Show (1986), his first film on AIDS, made with Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. While Adair’s legacy in observation and intimate conversations provide the film’s muscle, the beating heart of Absolutely Positive rests in the story of one HIV-positive Black woman, Doris Butler.

A secret diagnosis

Of all the interviewees, producer Janet Cole says, Butler came to Absolutely Positive late (almost a year into the process) but emerged as the film’s anchor. “We were floundering at that point,” Cole remembers. They’d interviewed several HIV-positive women of color, but only Butler and Alice Terson, a lesbian activist who died in 2009, continued with the film. Butler, a Black mother with a young son with AIDS, provided the emotional core of Adair’s meditation on life and death. Her role in the film also led Butler into public advocacy, part of what she called her “battle for life”—a life that was cut all too short.

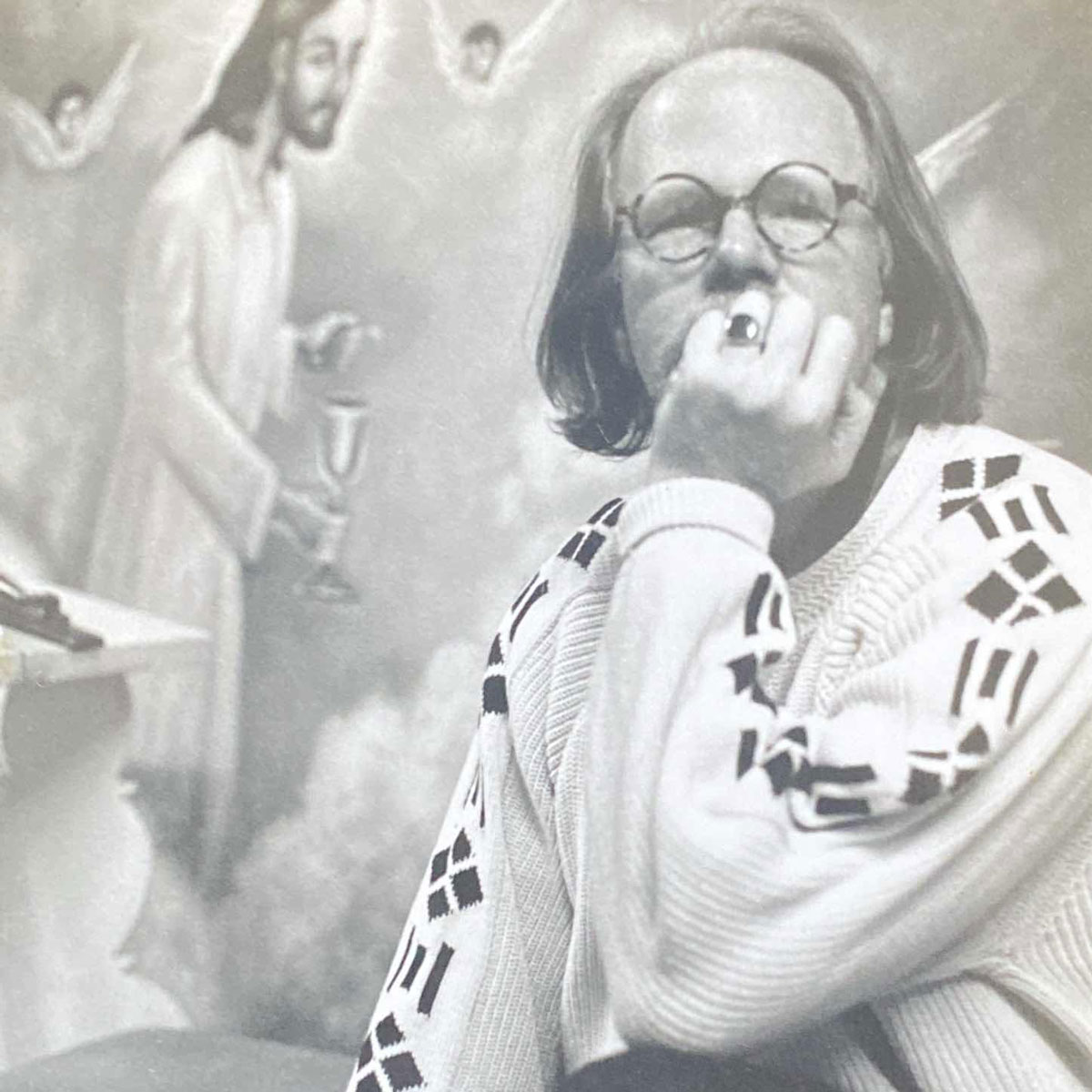

Butler’s life before HIV included a tumultuous childhood and a period of IV-drug misuse. But by the mid-80s, she and her husband had been sober for years. As a soprano in San Francisco’s Neighborhood Baptist Church choir, Butler found solace and a community—likely a source of comfort as she experienced several miscarriages before the birth of her son, Jared. Though born seemingly healthy, as a baby Jared became sick regularly. It wasn’t until Jared’s doctor diagnosed him with AIDS that his parents were tested. Butler opened up her results on a MUNI train home. In an interview that didn’t make the final version of the film, she describes the world falling away as she held the letter in her hands.

While Absolutely Positive provides a window into her personal pain, it also bears witness to a woman stepping into her own power. Keeping their diagnoses a secret for little over a year took a toll on the family. Her husband (who was HIV-negative) relapsed and entered a treatment program. Butler feared losing her community. She recalled later, “I felt that if they had found out about us, we’d have to leave the church.”

Butler’s decision to go public concludes Absolutely Positive. Her pastor would become her champion, arranging with Adair and Cole to pre-screen the film at the Neighborhood Baptist Church. As the congregation watched Butler’s hidden struggle with HIV unfold on screen, their shock turned into unwavering support.

‘We are not just getting sick and dying’

Not long after Absolutely Positive aired, Butler became a sought-after public speaker for AIDS organizations, and served as the first board president of Oakland’s HIV-positive woman’s organization, WORLD. WORLD founder Rebecca Denison credited Butler with helping her understand how important it is for Black women and women of color to have their own spaces within the larger community of women’s organizing.

Despite these accomplishments, the realities of Butler’s life were unrelenting. Jared died in 1992; she would later tell audiences or readers, “My world fell apart.” Between her grief, her husband’s challenges with sobriety, and her strained relationship with her daughter from a previous relationship, Butler went on stress leave from her job at Kaiser Permanente and was eventually fired.

She navigated the challenging network of community organizations and social services around her. “I needed the system and learning how to utilize it was a full time job,” she recalled in one presentation. The Berkeley-based organization World Institute on Disability (WID) hired her as a part-time peer educator in their AIDS project; she spoke at the 1993 International AIDS Conference in Berlin through this work. At WID, Butler began seeing her own issues in a different context. “Through my exposure to the staff, many of whom are disabled, I am beginning to identify more as a disabled person,” she said. “I realize the disability system has many services and tools I can use to cope [while] living with my HIV.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 included both HIV and depression in its definition of disability, but Butler brought those two issues even closer. Often crediting her faith, and faith in herself, as a source of huge support through her experiences of depression, Butler advocated for solo and family therapy which she could more easily obtain via disability and HIV resources.

The WID AIDS Project lasted from 1990 to 1997, successfully running an AIDS peer-support group for Black women at Highlander Hospital, and training disability providers on HIV services and HIV-service providers on disability services. Butler would remark at these trainings that people living with HIV weren’t always at death’s door. “We are not just getting sick and dying but living longer and healthier!” she said. When Butler passed away in 1996, hundreds attended her funeral. Her family was surrounded by people from every community she worked with.

This year marks a bittersweet 25th anniversary. In 1996, life-extending cocktail HIV treatments dramatically shifted the course of the disease in the United States. But for Butler and Peter Adair, those treatments didn’t arrive in time. The director and his documentary subject passed away just months apart from each other. Today, only three of the original 11 participants in Absolutely Positive are alive.

Thirty years after it showed on PBS stations (including KQED), Absolutely Positive remains a rare example of a documentary film that allows people to speak for themselves, on their own terms, especially when it comes to illness and death. And thanks to the care of Adair and his team, Butler’s legacy lives on.

You can stream ‘Absolutely Positive’ through Apple TV. More of Peter Adair’s films are available on the Criterion Channel.