On Nov. 14, Etel Adnan died in Paris at the age of 96. Her life was an expanding triangle: artist, poet and thinker. She is survived by her longtime partner, fellow artist and editor Simone Fattal. The daughter of a Syrian Muslim father and a Christian Greek mother from Smyrna, Adnan was born in Beirut in 1925. She studied in a French Catholic school in Lebanon where no other language but French was tolerated. At home, her father spoke Turkish, her mother Greek, and outside their home, she heard Arabic spoken on the street. She studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and continued her studies at UC Berkeley, where she fell in love with the geography and ethos of the San Francisco Bay Area.

That overseas trip in 1955 caused a transfiguration in her character. She found her measure, rhythm and pause in the English language she came to master. She developed a Dionysian aphoristic style, terse and clever, worthy of comparison to Emerson. English liberated her from the bounds of “professional writing” as defined by French culture, opening the doors to something more experimental, something we might now label punk. She entered the realms of what John Keats famously described as the chameleon-like qualities of the poet—a person without a fixed identity. Despite being born and raised in Lebanon, Adnan always cheekily described herself as an American poet and a California artist.

Establishing her linguistic identity gave way to an autonomy that allowed her to express her position in the face of a motley crew of historical catastrophes, including the Suez Canal crisis and the struggles for the independence of Algeria. But it also freed Adnan to channel her impetus—her burgeoning élan vital—into new artistic practices.

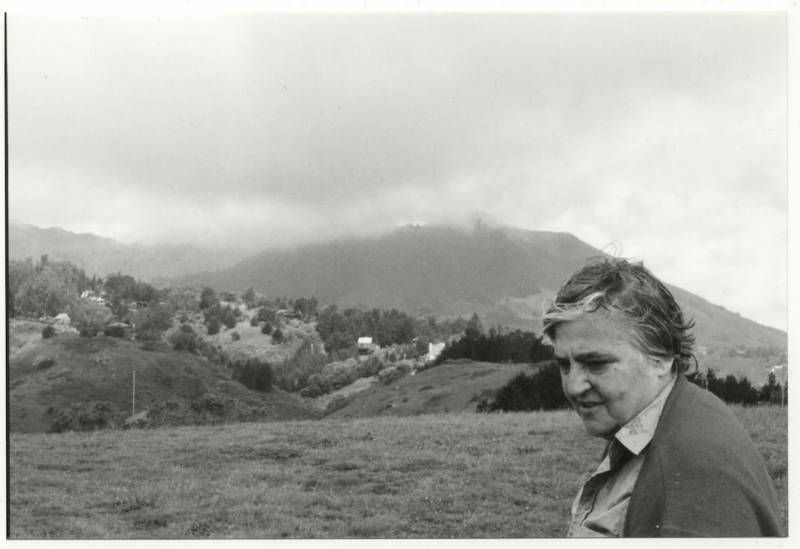

Art making did not come into Adnan’s life through the path of a professional career, but while she was teaching philosophy at Dominican College of San Rafael between 1958 and 1972. Her classes on aesthetics included readings from Wassily Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art and Paul Klee’s diaries. The head of the art department was artist Ann O’Hanlon, who gave her some pastels with the suggestion to explore the assumptions underpinning the class readings. With discipline, Adnan turned that moment into a grammar of painterly stains made up with felicitous contrasting colors. Recurring symbols appear in her paintings, prose and poems: mountain, sky, sun and sea. Mount Tamalpais became her grounding symbol and dominant metaphor, hundreds of times revisited and seen from a unique interior toponymy. And then it became the manifestation of the voyage itself.

It was simply a matter of time before the words, watercolors and ink found their way into the designs of her Leporellos, the first of which she made in 1961. These delicate manuscripts—done in Arabic calligraphy with motifs on accordion-folded paper—mix verses of Sufi poets and traditional litanies. In this context, writing ceases to be an artifice of communication. Instead, words and images become luminous, drawing on the silence of the white page and surging together to create meaning.

The Six Day War, the repression of the Palestinian people and tensions in the region motivated Adnan to move back to Lebanon in 1972 to begin dispatching polemical essays, and to write the masterful Sitt Marie Rose (1978), a novella reflecting on the themes of gender, race and politics that she continued to pursue elsewhere.