I first remember seeing Vicente Fernández perform on the Mexican television show Siempre en Domingo, when I was a kid growing up in Eastern Washington. Fernández, who died on Dec. 12 at 81 years old, would amble across the stage in his charro outfit, backed by an expansive ensemble of mariachi musicians also decked out in charro gear.

Like many Mexican Americans, I often heard Fernández’s music on the radio, in the car and at seemingly every party. He provided a soundtrack for our lives. But seeing him on screen was different. He wasn’t just a singer—he was the consummate Mexican ranchero. He was proud. He was dashingly galante in his traje de charro. In movies, he depicted valiant outlaws and cowboys. His dense mustache and stern facial expressions spoke volumes. And he seemed just as comfortable crooning to sold out-arenas as he was tending to stables on his ranch.

What I loved about Fernández was his true-life “rancho to riches” story, in which he never left el rancho even as he rose to become one of the world’s most famous and successful musicians. He embraced his upbringing on a farm and even glamorized it when he turned his rancho near Guadalajara into a tourist attraction complete with a performance venue and restaurant. He was beloved across the globe in not just Spanish-speaking countries, but also places like Romania, where mariachi music has a cult following.

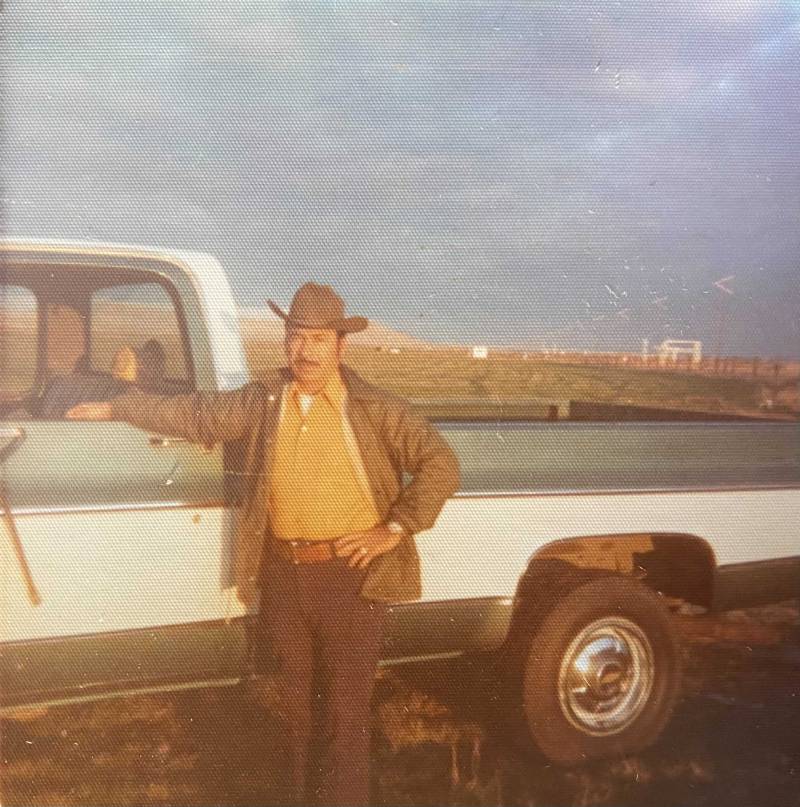

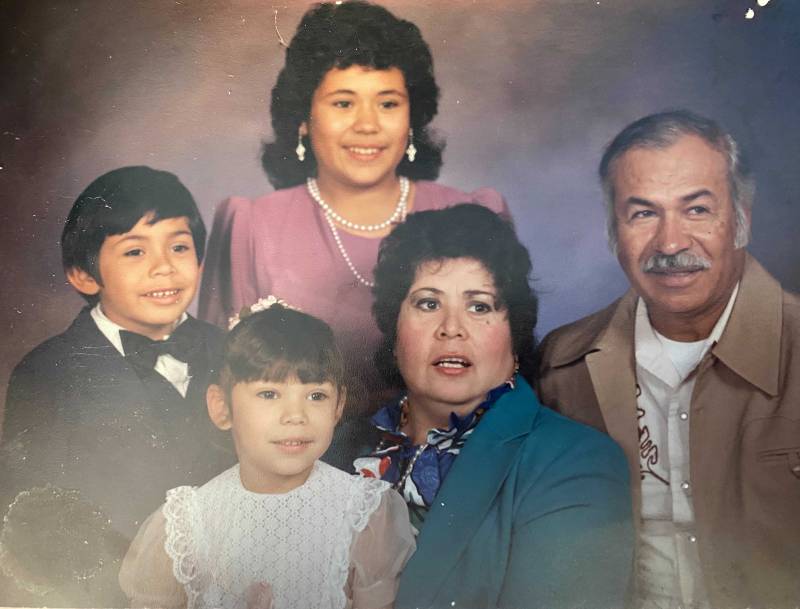

That’s pretty remarkable for a ranchero, a class label similar to “hillbilly” that was widely seen as backward, low class and pitiable. Looking down on rancheros wasn’t just tolerated, it was expected. When I was growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, asking someone if they were born on a ranch was a common way to denigrate someone for being shy, rude or socially awkward. Even in my household, my parents remarked about how their love transcended social barriers. My father came from el Rancho Colorado, a small settlement outside of Huejuquilla el Alto, Jalisco, the town where my mother grew up. People still ask my mom how she, an educated teacher, ended up marrying a ranchero like my dad and moving to the United States for him. Crossing class lines, especially during my parents’ generation, was considered taboo.

My parents were of similar age to Fernández—my father a decade older, and my mom born the same year as him, 1940. Like my dad, Fernández grew up poor on a ranch and eventually left to find better economic opportunities. My parents eloped in 1974 while my mother was on vacation in California visiting one of my aunts. I knew from an early age that my parents were not like other kids’. First of all, my parents married later in life. My father was 50 and my mom was 40 when I was born. My dad had gray hair for the whole time I knew him—he died when I was 15.