W

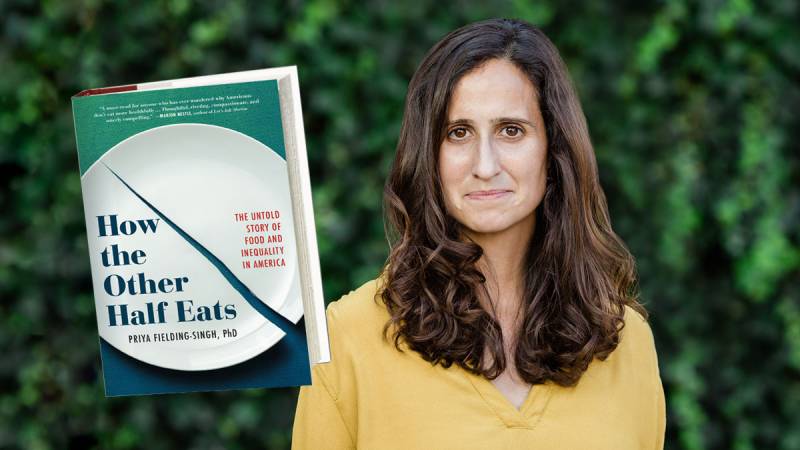

hen people read the title of sociologist Priya Fielding-Singh’s new book, How the Other Half Eats, they might assume that it’s about how poor people eat. And it is that, in part. But in fact, Fielding-Singh tells me, the book is an attempt to assess how all Americans eat.

“Everyone’s ‘other half’ is somewhat different,” the Utah-based sociologist says.

Out since November, How the Other Half Eats is the product of years of ethnographic research, most of which Fielding-Singh conducted when she was a doctoral student at Stanford. Which is to say that the book is, among other things, very much a document of the Bay Area in specific. It’s a portrait of how food inequality plays out in a place that has a nearly unimaginable wealth disparity—a gap that’s widening year by year. To understand how that inequality plays out on the dinner table, Fielding-Singh interviewed 160 families across the demographic spectrum, closely shadowing four of those families—four mothers, in particular, who share their food-related hopes and frustrations.

The book is wide-ranging: It delves into how trying to force your kid to be a less picky eater is mostly a luxury afforded to the relatively affluent. (Low-income families can’t afford the wasted food.) It explores the use of food as a signifier of social status. It devotes multiple chapters toward assessing the disproportionate balance of time and emotional labor that mothers, across all demographics, have to spend feeding their families.

Perhaps above all, the book is a referendum on American policymakers’ recent focus on food deserts—the idea that the main reason why low-income folks don’t eat as well is because they don’t have access to a supermarket in their neighborhood. Eliminating food deserts was, for instance, one of the core tenets of First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” initiative.