Ask even the most ardent fans of The Residents about their first exposure to the art rock group, and their responses are likely to focus on the visual rather than the aural—the unsettling, unforgettable sight of four men in top hats and tails whose heads have been replaced with giant eyeballs.

“My first memory of seeing The Residents was on Night Flight back in the ’80s,” remembers graphic designer Aaron Tanner. “However, I was too young to comprehend what my still-developing brain had actually witnessed. Fast forward to the early ’90s when Primus covered ‘Sinister Exaggerator,’ and all of those memories of ‘creatures’ with eyeballs for heads came flooding back.”

Or as Death Grips drummer and co-founder Zach Hill puts it, “Being a Bay Area/Northern California native, the eyeball was like the weirdo kids’ Mickey Mouse. And you’d see it before even knowing what it was.”

Bay Area mainstays The Residents remain masters of media and mystery. Though the band has been around in one form or another since the late ’60s, no one is entirely sure who the members of the group are (although there are some theories). The enigma has an undeniable allure, and The Residents add to their strange appeal through off-kilter music—jazz-inflected psychedelic rock and electronic experimentation that warps and wriggles like a worm under a heat lamp. Their striking album art, film and video work, and eye-popping stage performances make them all the more intriguing.

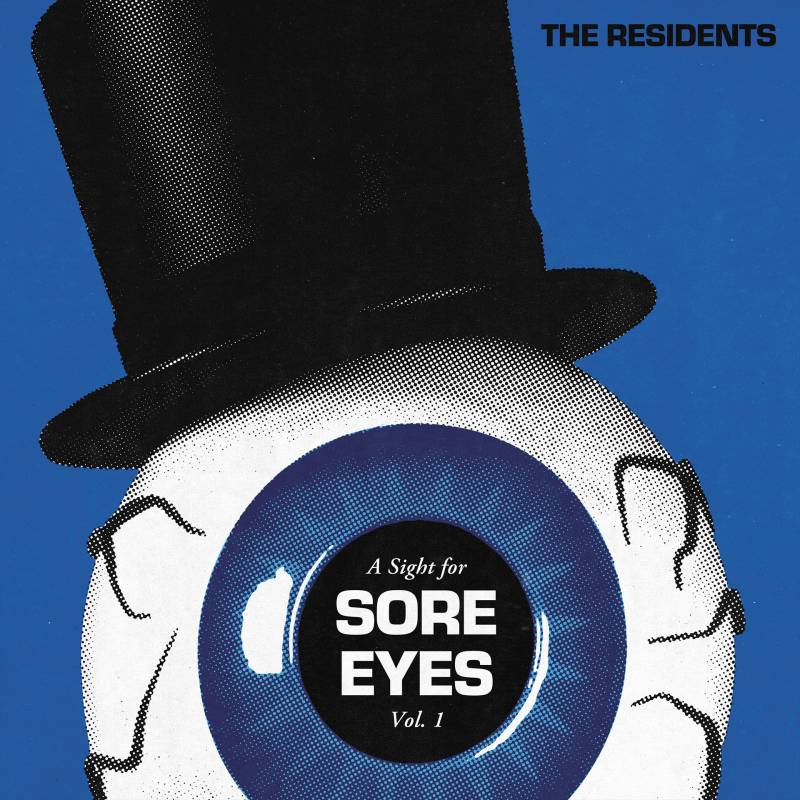

It feels entirely appropriate then that the first official book to track the history of this unique group, The Residents: A Sight For Sore Eyes Vol. 1 (out Jan. 7 via Melodic Virtue), is an almost entirely visual document. The hefty tome tracks through group’s evolution from their earliest days as hippie dropouts who landed in San Mateo in 1968 to their 1983 performances of The Mole Show, a stage show featuring magician and collaborator Penn Jillette. The volume is a sumptuous feast of photos, film stills, promotional material and collages of critical reactions to the music. (“Somehow, I thought of it as sounding like what Steely Dan or Frank Zappa might sound like on strong acid,” said one critic of the Residents’ 1977 album Fingerprince.)