D

eep clean your home, settle your debts, and get your haircut. Lunar New Year is just around the corner. In Vietnamese culture, the holiday is known as Tết, and this year it falls on Feb. 1.

Here in the Bay Area, Tết provides no shortage of opportunities to participate in tradition and culture, but the holiday and its seasonal eats aren’t prescribed or stagnant. Diasporic Vietnamese communities have always been proficient at recreating nostalgic homeland flavors with local ingredients—incorporating, for instance, Mexican jalapeno as garnish for what we know as American-style phở.

Now, nearly 50 years after the first wave of refugees arrived in the United States, Vietnamese Americans are still finding ways to augment the foods associated with Tết. In San Francisco, San Jose and beyond, young, 1.5- and second-generation Vietnamese chefs are using banana leaves instead of arrow leaves for rice cakes or lucky sticky rice dyed with red coloring in place of baby jackfruits. In doing so, pop-ups like Het Say Cali, Claws of Mantis and Bánh Chưng Collective pay homage to tradition while also helping to evolve Vietnamese American cuisine—and creating more inclusive, new communities along the way.

Hết Sẩy Cali

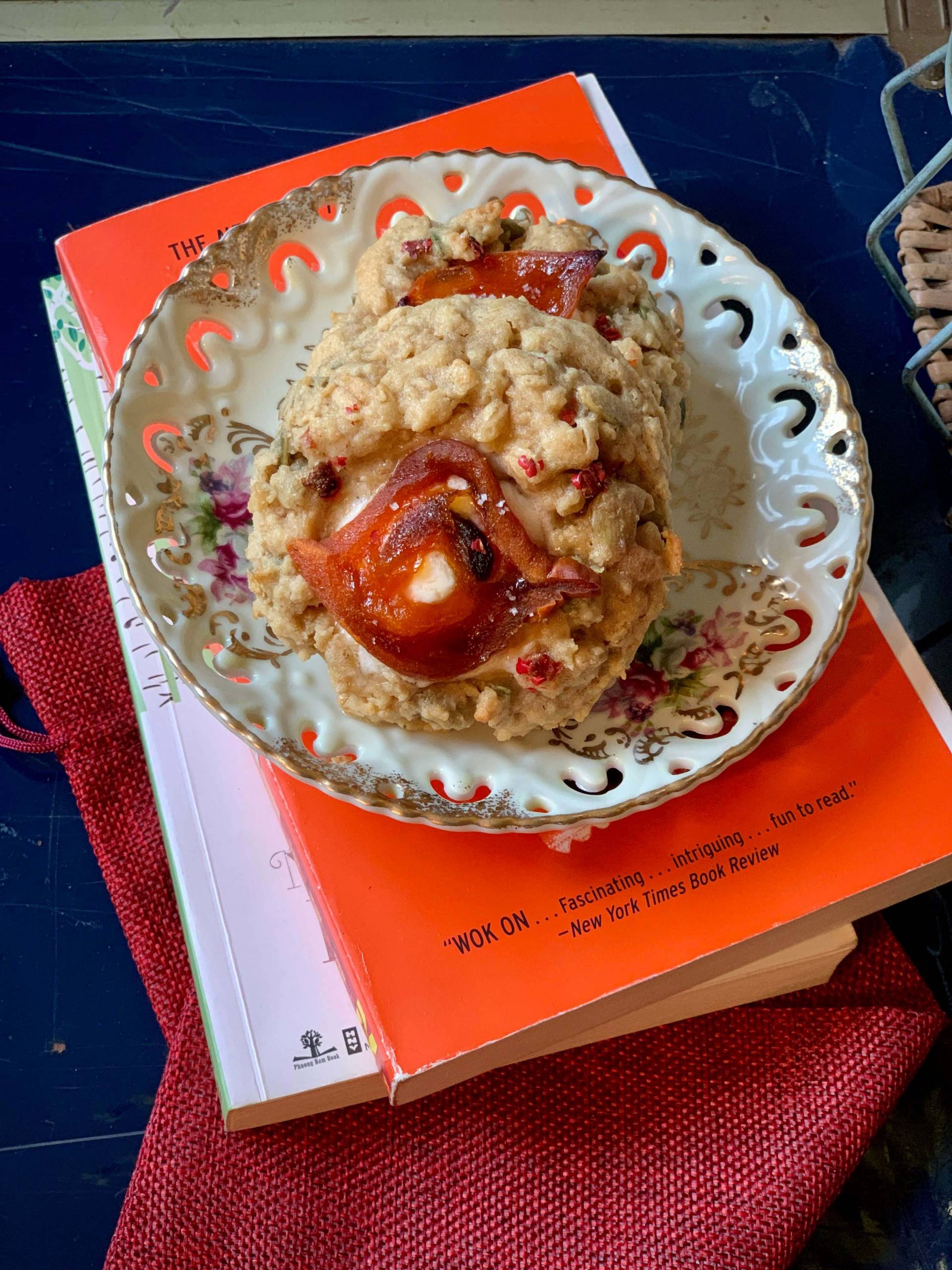

Hết Sẩy Cali, a colorful pop-up at the Rose Garden Farmers Market in San Jose, approaches Lunar New Year as just one part of its founders’ continued practice in honoring the craftsmanship of regional Vietnamese cuisine—always with plenty of verve and style.

Every Saturday, you’ll find the booth decorated in vibrant Vietnamese opera paraphernalia. Owners DuyAn and Hieu Le, who dress just as colorfully, became engaged after only three days of knowing one another. Their Tết offering is a continuation of their decade-long love story—one that includes a passion for DuyAn’s Miền Tây heritage, the Northern California landscape of Hieu’s upbringing and the couple’s desire to carry on the culinary legacy of Eastside San Jose.