L

ike many immigrants from the former Soviet Union, I’ve been glued to my screen in horror since last week, unable to look away from the real-time updates of Russian forces attacking Ukraine. Videos of women, children and elderly people hiding in bomb shelters and of explosions going off outside of people’s windows have sent our community into distress.

Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine feels particularly vile because it’s so contrary to the kinship many people from both nations feel. I was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, and as a child I immigrated with my family to the Bay Area in the late ’90s, joining a multi-ethnic wave of post-Soviet immigrants and refugees. In Russian-speaking pockets across the United States, Russians, Ukrainians, Armenians, Georgians, Belarusians, Kazakhs and many other ethnic groups broke bread, raised children and helped each other acclimate to our new country. I grew up with a Ukrainian stepfather from Odesa, and thanks to him, I have U.S. citizenship and an American-born younger sister who is half Russian and half Ukrainian.

That experience is not uncommon. When I went to the anti-war protests outside of San Francisco City Hall last Thursday and Sunday, I heard speeches in Ukrainian, Russian and English. Russian-speaking Ukrainians were prominent among the turnout, but I saw protest signs that indicated that Russian, Latvian, Azerbaijani and Taiwanese people were also there in solidarity. As Russia and NATO continued to face off in a geopolitical chess game of superpowers, everyday people showed up to hold each other in mutual grief and support as many awaited updates from family members hiding from bombs in Ukraine.

“We’re terrified,” said Bay Area author Masha Rumer when I met up with her at the protest on Feb. 24. Born in Russia to a Jewish family with roots in Ukraine, Rumer came to the U.S. as a refugee in the early ’90s. “I know some family members right now in Kyiv cannot leave because the air space is closed, and they cannot get enough fuel to get out of the country and they’re afraid for their safety and the safety of their child,” she said.

Rumer’s book Parenting With An Accent builds bridges among immigrants of different cultures, and that’s what she hoped to see at the rally. “Many of us left the former Soviet Union because we don’t agree with the policies, and yet we’re still finding it reverberates all over the world all over again,” she said. “It’s a very complicated relationship. Many of us speak the Russian language, which was forced upon people from across the former Soviet Republics. But at the same time, it’s the language we grew up with, and now we’re finding ourselves in a difficult time where we’re ashamed of what the government is doing.”

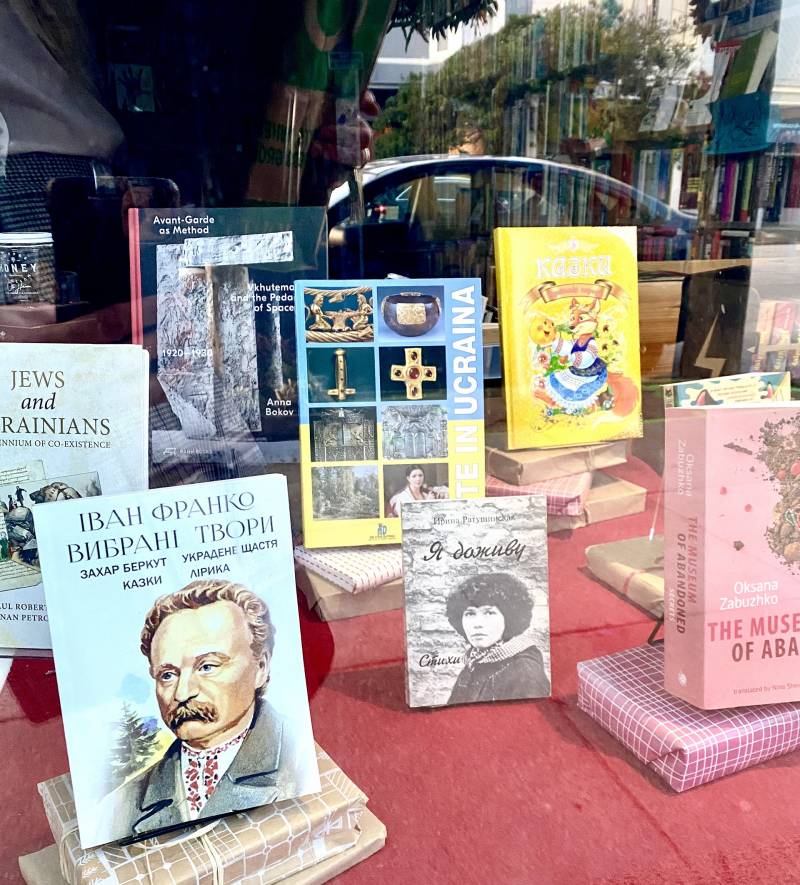

Anastasiya Mutungi, manager of San Francisco Russian-language bookstore Globus, expressed similar feelings when I spoke with her on the phone late last week. She immigrated to the U.S. from Belarus in 2009 and said she feels “accountable and responsible” that the government of her home country is supporting the aggression. She changed Globus’ small, Richmond district window display to feature books by Ukrainian authors.