I

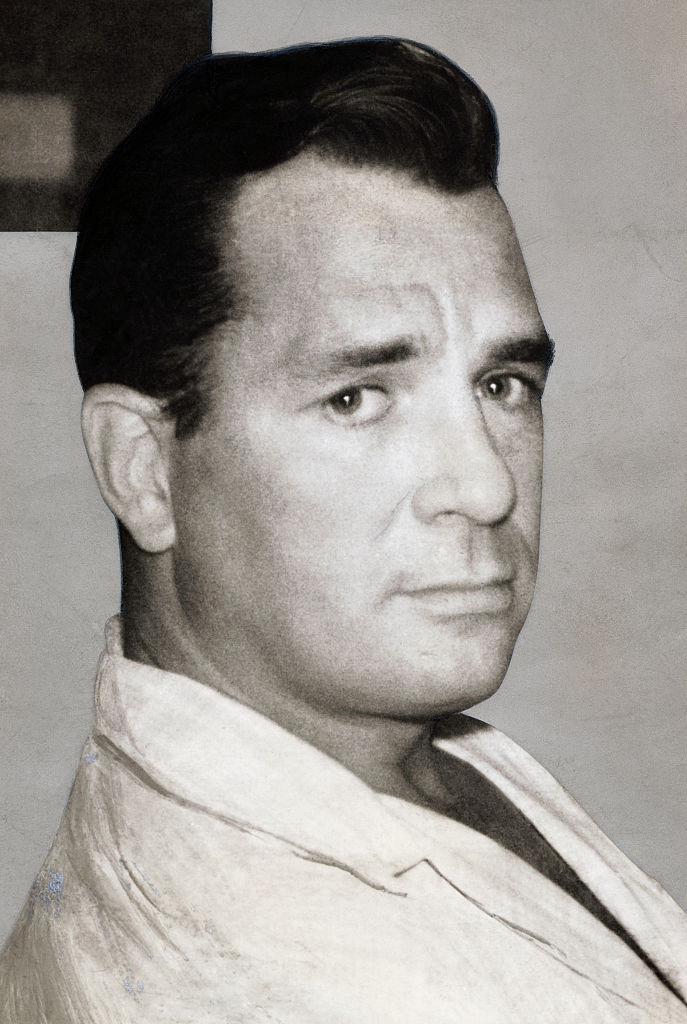

first met Jack Kerouac not long after my country and I split up. By that, I mean I had just moved to the United States from Colombia, where I was born and raised. I first encountered him during my first semester at Rollins College in 2012, and his work changed my artistic approach.

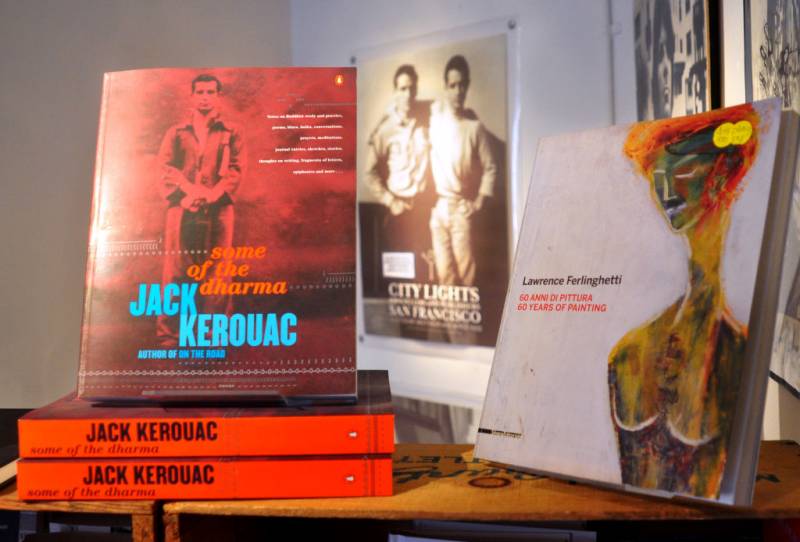

After reading On the Road for the first time, I went to my college library’s archive and spent hours looking at the manuscript from The Dharma Bums, written when Kerouac was living in Central Florida, not that far from my alma mater. The novel I am currently working on had a working title directly derived from one of his quotes. The aforementioned novels and novellas, as well as others by Kerouac like The Subterraneans, Big Sur and San Francisco Blues, have included the Bay Area among their settings. And the literary scene he helped build here was one of the factors I took into consideration when I decided to make the Bay Area my home.

This Saturday, March 12, is the celebration of Kerouac’s centennial. This past Thursday, San Francisco’s City Lights, also a publisher of eight Kerouac books, celebrated this occasion with a packed online event. Other events in significant places in Kerouac’s life, like Lowell, Massachusetts—where he was born—are also planned in the coming days.

A writer of spontaneous prose, lover of jazz, idealizer of México and adopter of Zen—Kerouac is a fixture in the United States’ counterculture mythos. But his legacy comes with a lot of baggage, especially in the way he depicted African American, Latinx and Japanese people in his writing, to name a few.

That’s why I talked to five different creatives residing in the Bay Area about Kerouac’s complex legacy. They acknowledged all that he did for the Beat generation and literature in the U.S., but also spoke of how many of his ideas valued aspects of non-white cultures but didn’t necessarily respect all of their differences.

Writer and journalist Roberto Lovato’s father, Ramón, worked at the Southern Pacific Railroad. He met Kerouac there during the 1950s, when Kerouac got a job at a San Francisco railyard. Lovato recounts the details in his memoir, Unforgetting, where he writes about three types of white men his dad encountered on the job.

The first kind was “racist, who would open [union] meetings by saying ‘ladies and gentlemen—and all you colored folks, too,’” he writes in the book. The second type was more “entrenched in the struggles and fighting side by side with Black and Latino workers. They were often socialists or belonging to some other left-oriented formation,” he says.

But Kerouac, Lovato’s father would say, was one of those who “showed verbal sympathy, but their actions showed the opposite; they viewed their fellow workers at Southern Pacific kind of as objects of liberal exoticism,” Lovato says. In our conversation, he referenced Kerouac’s “October in the Railroad Earth,” a piece of spontaneous prose where he narrates a scene from his time working as a brakeman. There, his white gaze is on full display.

“[This] behavior and attitude reflects the fetishization of the white liberal gaze that turns many of us Latinos into tropical sidekicks,” says Lovato. And that got me thinking: How much of the U.S. popular imagination of Latin America has been shaped by the perspective of people like Kerouac?