The amazing thing about art—especially art loosed from the constraints of particular movements and eras—is that it can be fresh and revelatory regardless of when it’s encountered. It’s a weird thing, a kind of time travel, to see decades or century-old paintings and feel them scintillate our eyeballs in 2022. Popular, much-reproduced work by so-called “masters” regularly does this in person, in part because the weight of art history tells us this work is beautiful and important.

But it’s another thing to encounter artwork that hasn’t had the benefit of decades or centuries of mythologizing, and to instead know in one’s own mind, heart and gut that this work is beautiful and important. Such is the case with the Alice Neel retrospective People Come First. First staged at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the show’s tour is making its third and final stop at the de Young, where it will introduce many to the painter’s six-decade-plus-career. I predict they’ll be unlikely to forget her.

The show opens with a 1944 photograph of Neel sitting cross-legged in her studio, surrounded by her “pictures of people” (she resisted the term “portraiture” as stuffy and conservative). This is an image of an artist wholly devoted to her craft: prolific; alone with the work, which rises in jumbled, haphazard stacks above. And yet this image also captures Neel surrounded by others—the friends, colleagues, family and neighbors she invited into her home studio and rendered in oil paint.

Throughout People Come First, the exhibition skillfully mingles both Neel’s epic biography and her subject matter in thematic rather than chronological displays. Born in 1900 to a white, middle-class family in Pennsylvania, Neel bucked the era’s expectations for her gender and social position. She joined the Communist Party; worked for the WPA’s Federal Art Project; took lovers; lived for 24 years in Spanish Harlem; and survived suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalizations, the death of a child, and the abandonment of a husband (who took their daughter back to Cuba). For many long decades, she also received little to no recognition from an art world obsessed with Abstract Expressionism.

In summary, Neel was a radical—both for the way she lived her life, and for what and how she chose to paint.

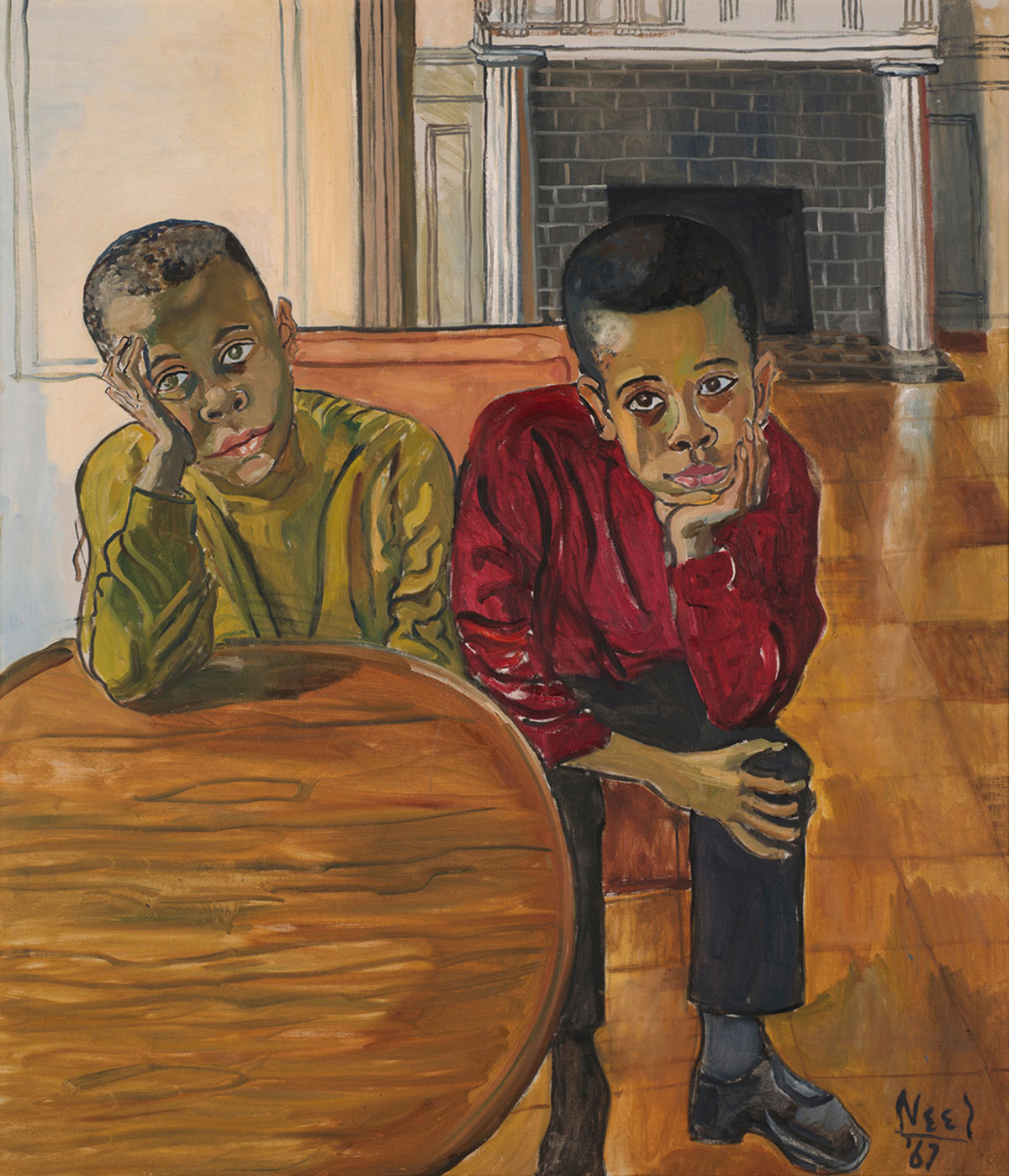

The exhibition’s title People Come First refers to a phrase Neel often repeated, asserting her belief in the dignity and importance of all human beings. As with any depiction of others, there is a power dynamic between the artist and her subject, a fact the exhibition wall text takes time to address, particularly in the 1972 painting of Neel’s Black housekeeper and child, Carmen and Judy. Neel’s privilege as a heterosexual white woman—even a poor one—definitely colored her interactions in leftist, civil rights and feminist communities, but it’s clear she traveled in remarkably diverse circles.