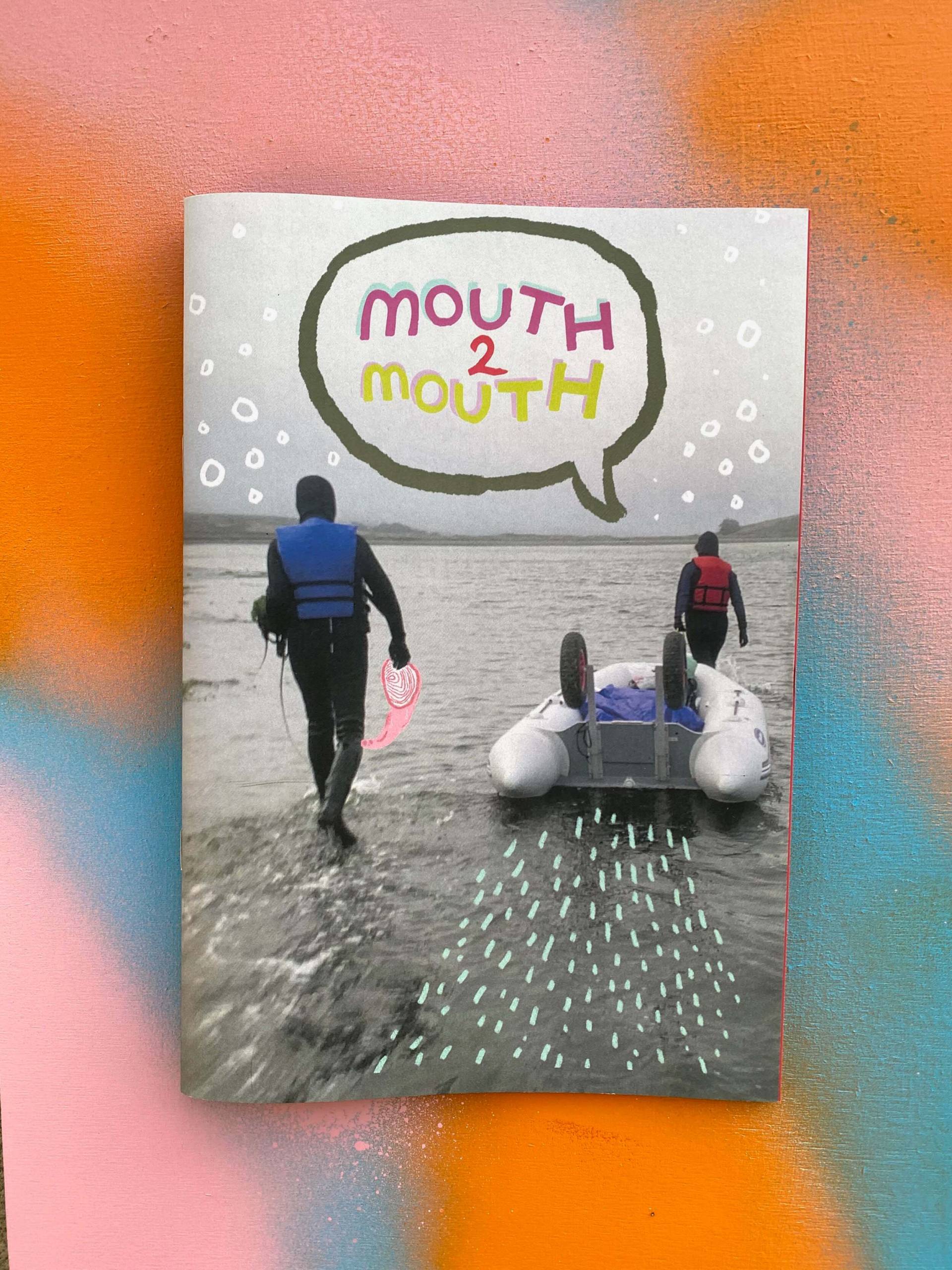

The coolest new Bay Area food magazine can’t be found in bookstores or on newsstands. Its masthead only includes a handful of professional writers—or actual “food people” for that matter. Conceived and born in San Francisco during the pandemic, Mouth2Mouth isn’t even really a proper magazine.

Instead, the publication comes out of another long and proud DIY tradition here in the Bay: It’s a zine. And it’s now soliciting submissions for its second issue.

The brainchild of San Francisco architect Hallie Chen, Mouth2Mouth has some of the same hip, arty, off-kilter aesthetic of the dearly departed food magazine Lucky Peach—but without the whiff of toxic masculinity that contributed to that publication’s eventual undoing. Chen was an obsessive Lucky Peach reader back in the day, and says she was missing that kind of literary, intensely personal storytelling—the kind of food writing where the food was “almost peripheral.”

“I think of food as a place—it’s this intersection of people and material and memory and space. … It’s more of an art project than a food thing,” Chen says of the zine.

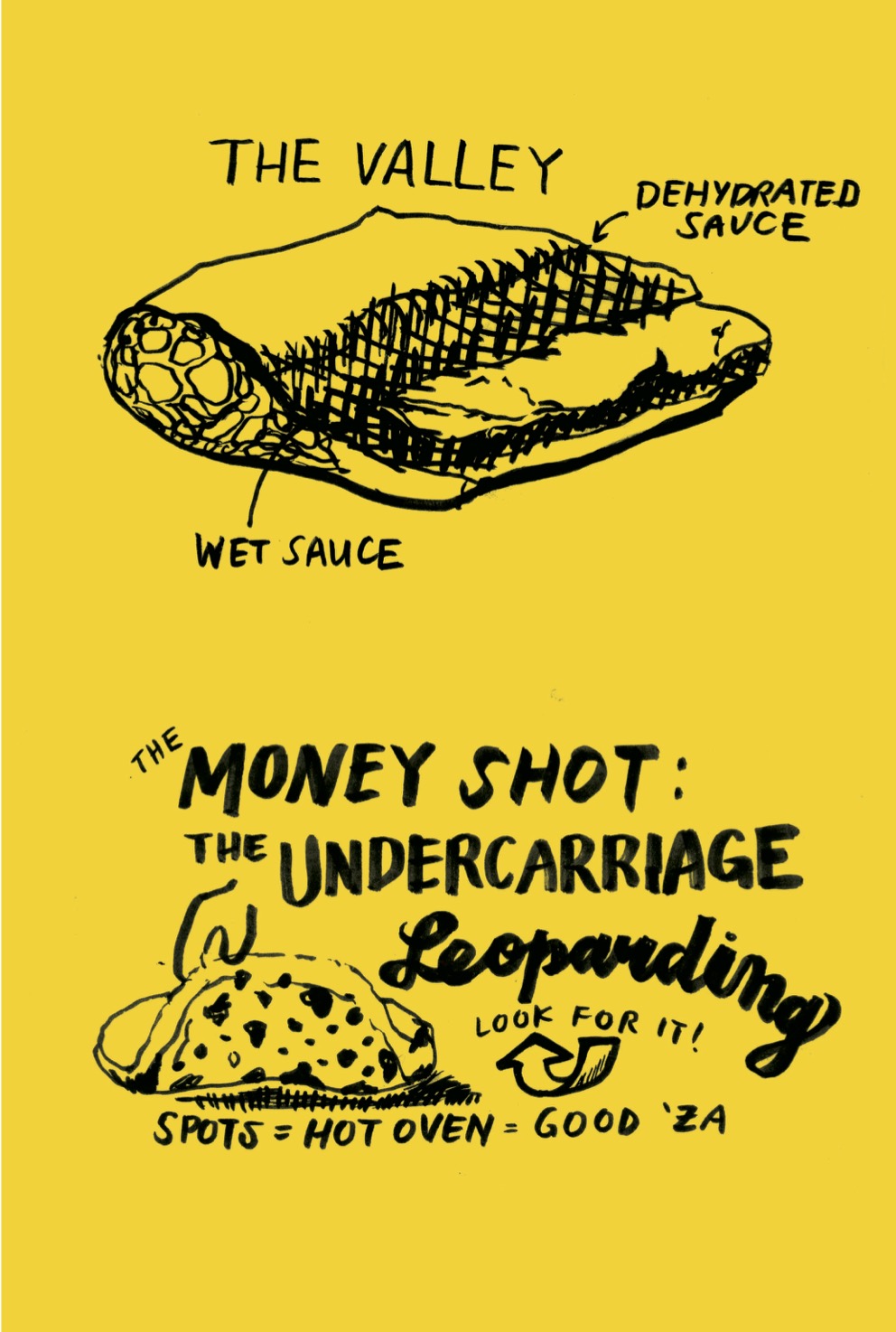

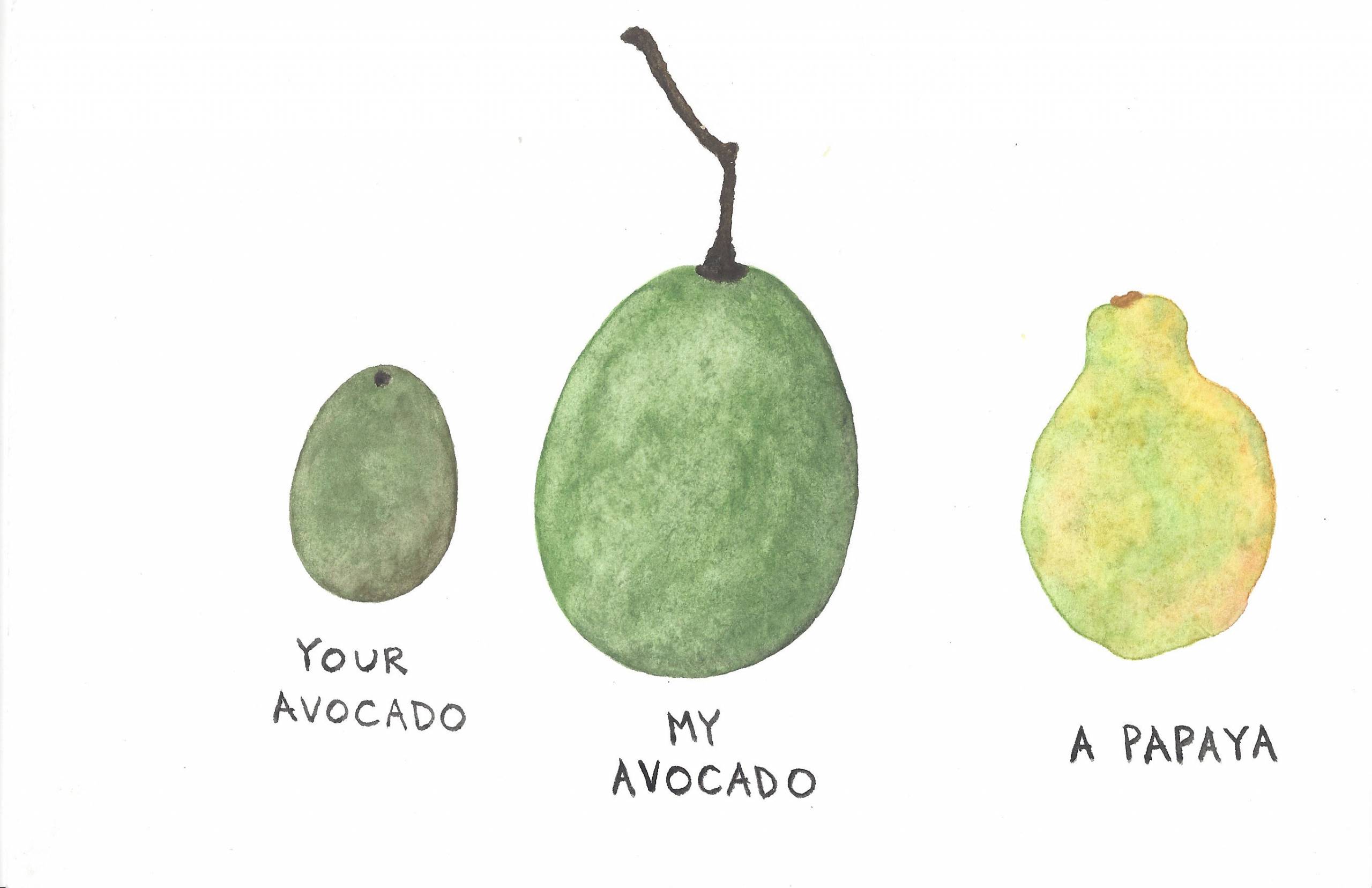

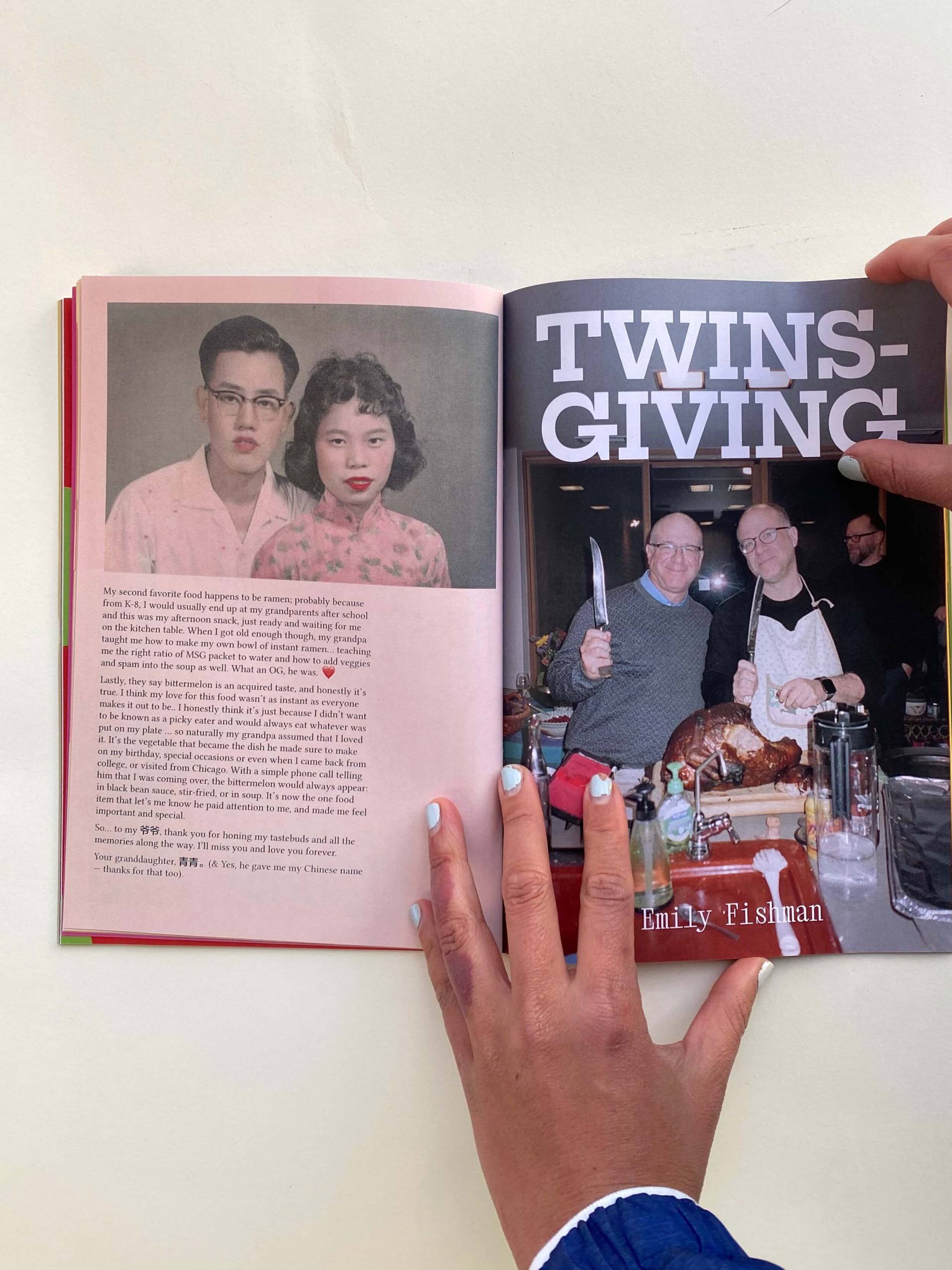

Mouth2Mouth’s first issue, published last spring, has a story about a Korean American woman digging for geoduck with her mother in the pre-dawn light of Tomales Bay. It includes a slew of nostalgic, heartfelt recipes—for flour tortillas, bánh bèo, Cheerios served over espresso—that are written in the form of poems, doodles and photo collages. One ostensible recipe, “How to Cook a Tiger,” by the writer Xiaowei Wang, traces the roots of Baoning vinegar to a village in Sichuan, China, and also digs into the history of anti-Asian sentiment in California in the early 20th century.