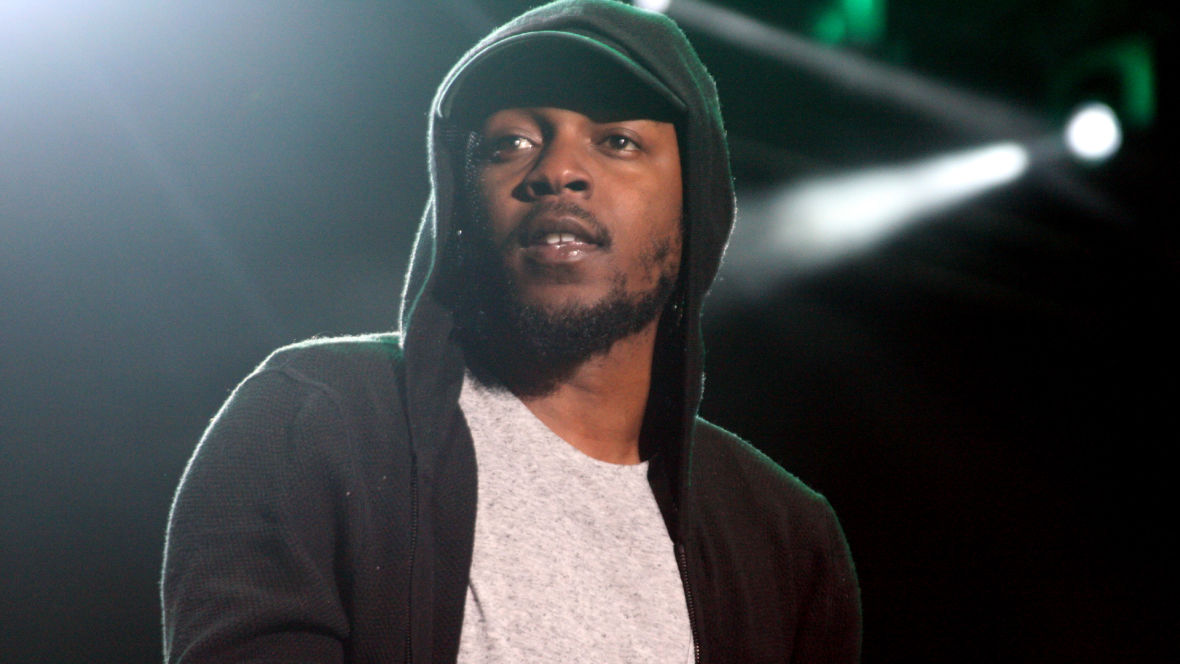

With Kendrick Lamar about to drop his fifth studio album, Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers, it’s the perfect time to argue about his most significant song.

In the half decade since Kendrick dropped Damn, fans have been left to revisit old tracks repeatedly during his hiatus. Which is fitting, because one of Kendrick Lamar’s greatest gifts is going back and revisiting—or rather, revising—his earlier music.

K-dot is a master of retelling the same story again and again, but on a larger level each time. If you listen closely, the arc of his musical output shows that refining and retelling your story, over and over, is an important aspect of growth, both as an artist and a human.

The king MC from Compton has done it with his “The Heart” series, often using that title as a jumpoff to spaz and let loose on the issues he’s dealing with at the time of recording. He dropped the fifth entry in this series this past Sunday just days before his full album release, as he’s done in the past. (In the video, he uses deepfake technology to morph into the likeness of Kobe, Nipsey and more.)