I

n October of 1968, a reporter from the San Francisco Examiner spent an evening inside a third floor office at 345 Franklin Street in San Francisco. By day, the place belonged to an attorney named Vincent Hallinan. After 7pm every Thursday, Hallinan offered his office—free of charge—for America’s very first post-abortion center.

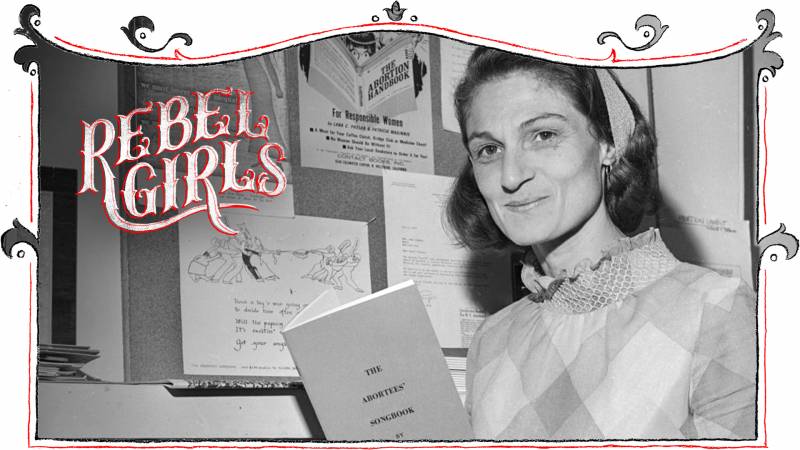

The free clinic was a safe space for young women who’d recently undergone illegal abortions and weren’t able see their regular doctors for post-operative care. The clinic also offered free pregnancy tests, birth control prescriptions and advice from a Planned Parenthood volunteer. It was staffed by volunteer gynecologists, a nurse, a receptionist and a lab technician named Pat Maginnis.

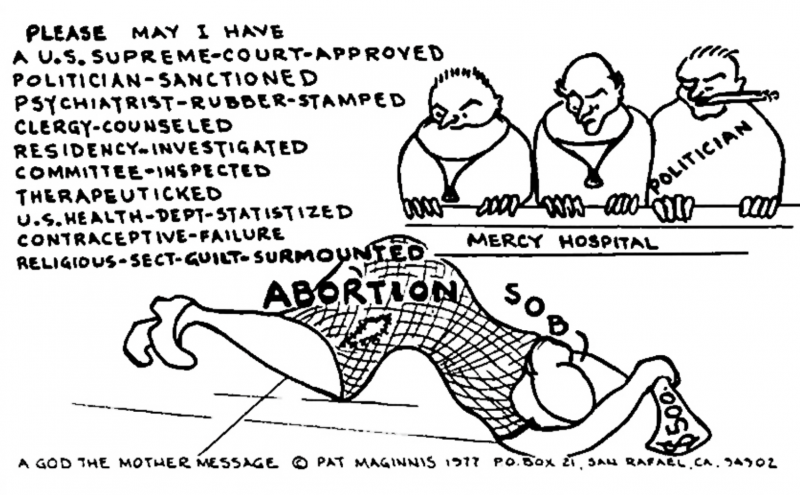

It was Maginnis who had started the clinic. It was she that was the most unapologetic about a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy. And it was she that told a waiting room full of young women that night in 1968:

Remember. Your abortion is your business and no one else’s. You have a right to silence guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment. Abortions performed outside of the state are not reportable to police.

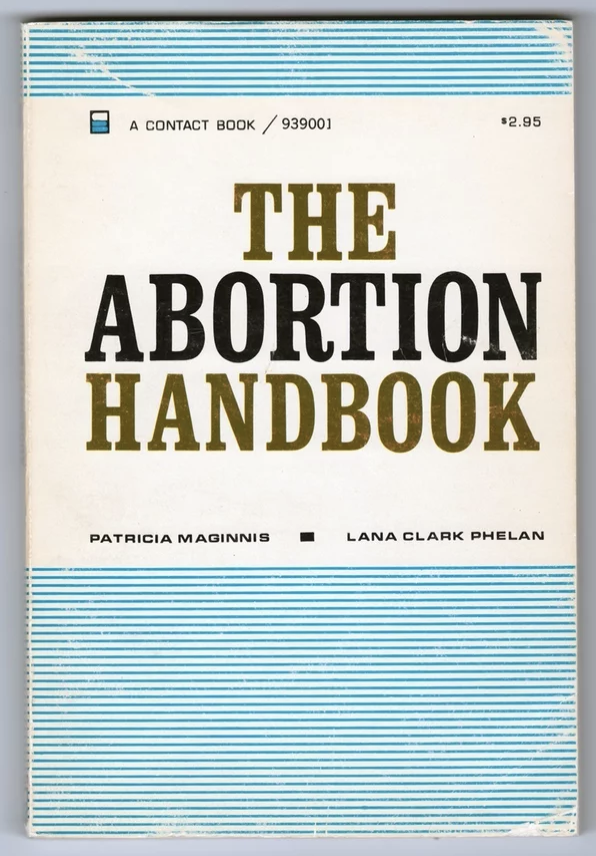

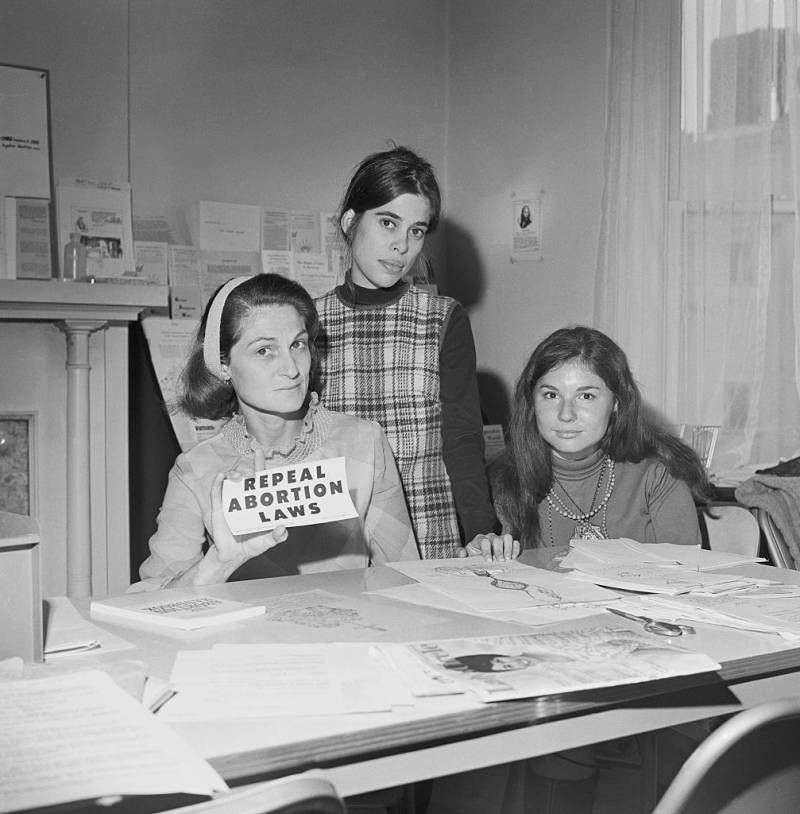

By the time the Examiner paid Maginnis’ clinic a visit, she was already a well-known figure in San Francisco, and a pro-choice thorn in the side of anti-abortionists across the country. In 1962, Maginnis had started the Citizens Committee for Humane Abortion Laws, which was later renamed the Society for Humane Abortion (SHA). In 1964, she co-founded the Association to Repeal Abortion Laws (ARAL), alongside Rowena Gurner and Lana Phelan Kahn. (It was a precursor to today’s NARAL Pro-Choice America.) Maginnis, Gurner and Kahn were such a force to be reckoned with that they earned the nickname ‘The Army of Three.’

The SHA and ARAL served different purposes, but enabled Maginnis and her likeminded campaigners to achieve goals on both an official and underground basis. Official operations included public campaigning and working diligently to change the laws of the day. Underground activities included the compiling and distribution of lists of safe abortionists, along with how much they charged.