Do you remember the last thing you said aloud?

No? That’s ok. Try saying this: “Wow.” Pucker up. Let the lips widen and whip around a small ball of air before returning to their pursed shape. “W-O-W.” Now do it again. See that coworker looking at you strangely? Invite them to join you. “Wow.” Keep it up, until it loses all sense and becomes pure sound.

If you’re still with me, you’ve already enacted the core principle of Bobby McFerrin’s performance practice: playful repetition. For McFerrin, there’s a thin line between spoken word and song. A simple “wow” from the crowd becomes a bebop solo or a chorale in four-part harmony.

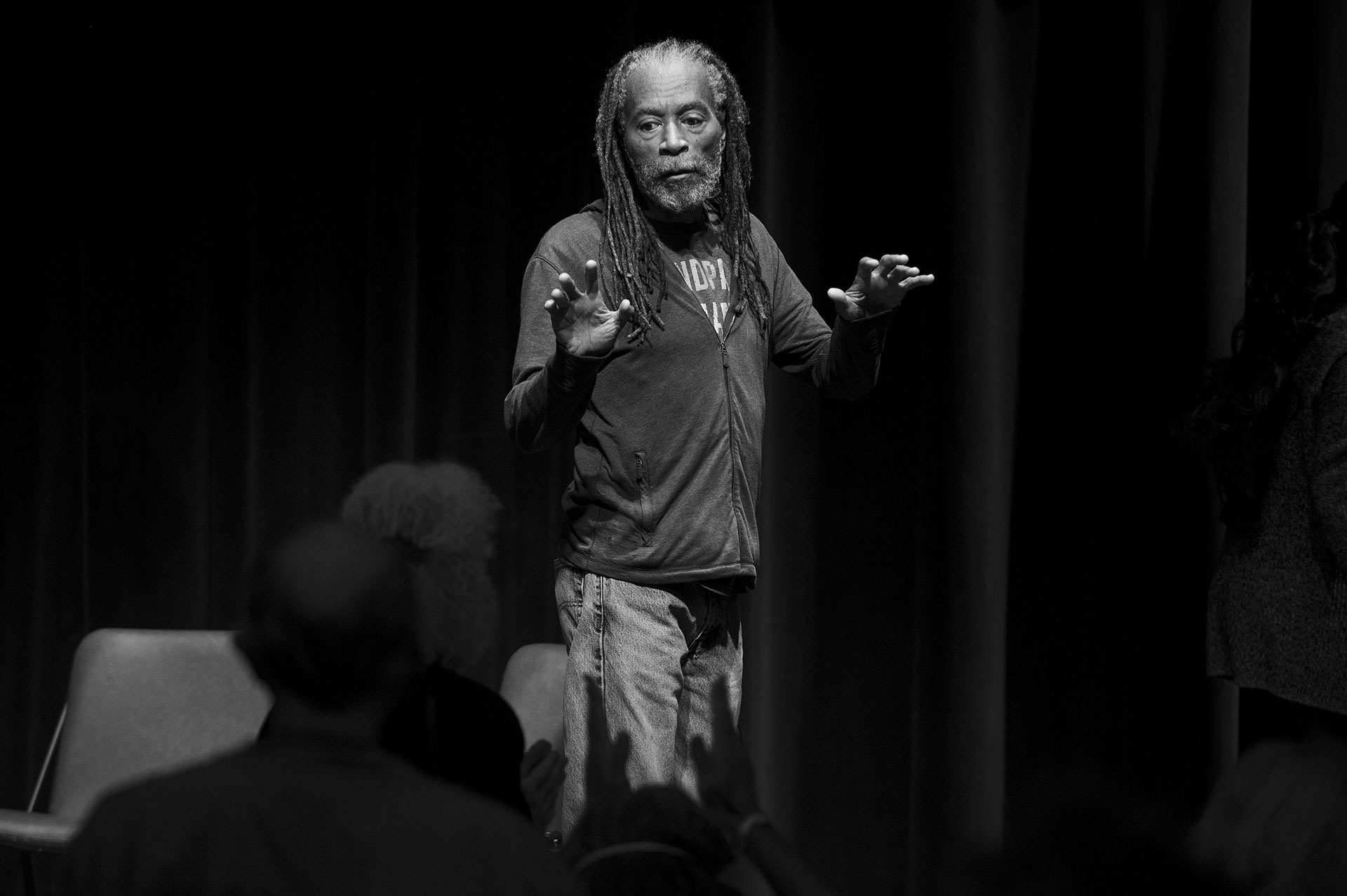

“As musicians,” McFerrin told me last week, “we say, ‘Okay, ready, set, play.’ And I take that literally. The stage is a platform for adventure…Everything is game.”

You might know McFerrin as the voice behind the 1988 hit “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” or even as one of the inspirations for Key and Peele’s “Kings of Mouth Noise” sketch. But scratch the surface of celebrity, and you’ll realize that McFerrin is one of the most inimitable musicians of the past 40 years: a virtuosic solo performer with a four-octave range, conductor of St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, and 2020 NEA Jazz Master.