I am afraid of forgetting, of losing my memory and seeing it merge with the dense waters of oblivion. I’m especially scared of losing the memories that anchor me to my life in Colombia. Because of all the strife, the war, the violence, people often call Colombia a country without memory, condemned to repeat its past. It’s a trauma that goes back to Spanish colonization.

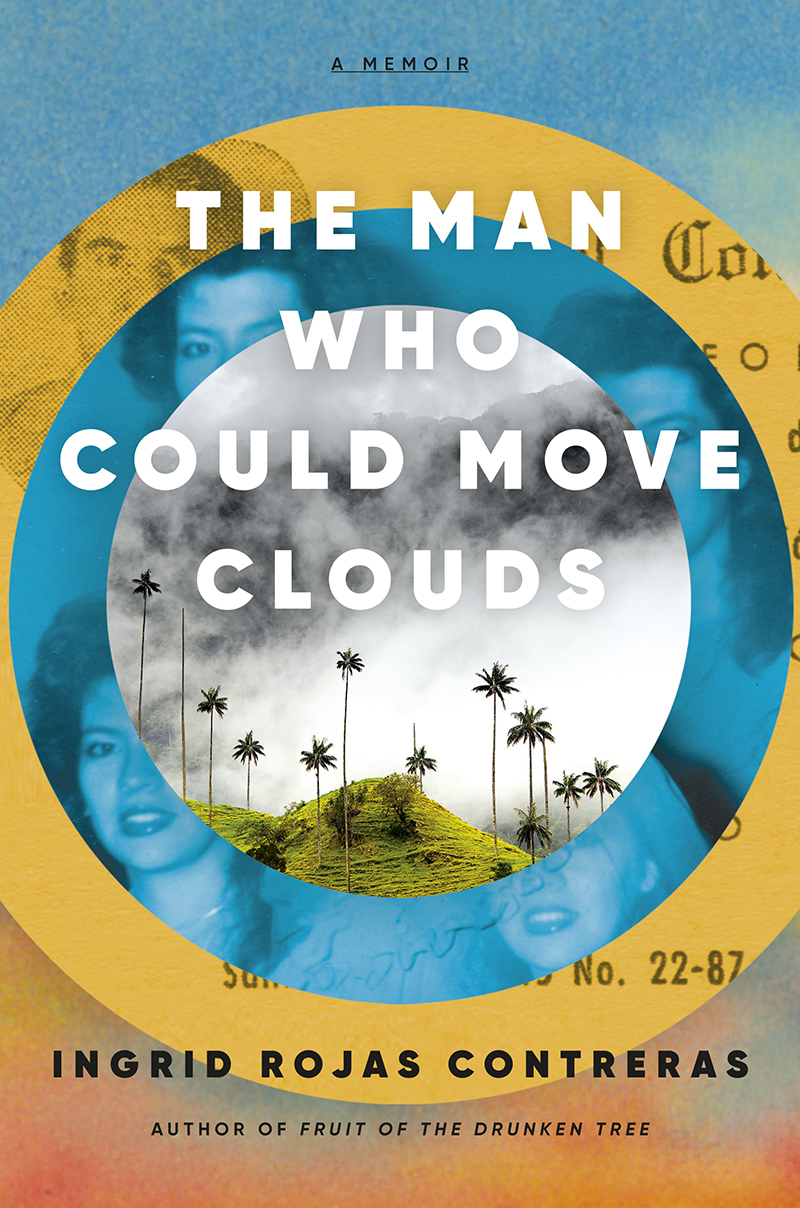

Ingrid Rojas Contreras, a Bogotana like me who has also written for KQED Arts & Culture, wrote a memoir with these very ideas titled The Man Who Could Move Clouds, which comes out July 12 via Penguin Random House. While reading Rojas Contreras’ phantasmagoric prose, Colombians like me will confront the ghosts of their own memories and families, while other readers will dig into stories about the loops and patterns that have defined so much of our home country’s history.

You could say that The Man Who Could Move Clouds is a memoir about Nono, a grandfather with ancestral secrets and gifts, and how his daughter, Sojaila, and his granddaughter, Ingrid, inherited them. You could also say that each of these people mirror each other in cycles that began before Colombia was even a republic. You could say the book speaks of anecdotal evidence of bilocation, telekinesis and other magic phenomena. But explaining what happened to Rojas Contreras and her family through this lens would be missing the point.

Using literary experiments, The Man Who Could Move Clouds tackles the author’s and Colombian society’s complicated relationship with memory. In a place where families hiding unspeakable secrets is the norm, speaking the truth is nothing other than magic. “When I decided to first write the memoir and I shared that with my family, they were like, you can’t tell this story. ‘What are people going to say?’” Rojas Contreras says. But living in the U.S. and having that distance allowed her to see “how beautiful that story is, and eventually convinced my family that the silence that they were asking me to keep around the story of our family was, you know, protecting oppression.”

With this memoir, and with the recent truth commission unveiling of lives lost in Colombia’s 58-year internal conflict, there’s a hope in how acknowledging the atrocities of the past can lead to change. “Sometimes the record that the state keeps keeps a lot of the truth out,” Rojas Contreras says. “To me as a writer, I think that oral history tells the story that the state doesn’t want to tell or that people in power are not interested in telling.”