A literary agent told me once that it’s important for writers to offer readers hope. It isn’t something easily found in the pages of this book. The collection does, however, provide important detail and fascinating personal narratives that highlight how Afghan women and girls embraced the opportunities afforded them over the past 20 years.

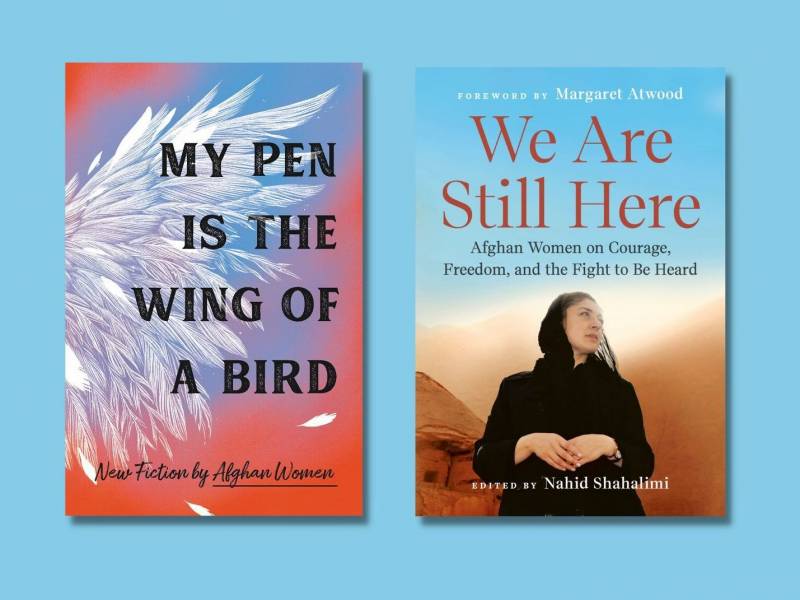

I did find hope, though, in the other anthology, My Pen is the Wing of a Bird—publishing in the U.S. in October. It includes 23 gut-wrenching stories translated into English from Dari or Pashto.

The collection’s 18 contributors were selected from among some 100 entrants to the Untold—Write Afghanistan project. The project was started in 2019 for women writers marginalized by community or conflict. Project founder Lucy Hannah writes that it isn’t safe at the moment to reveal detailed identities of the book’s female wordsmiths—some of whom use pen names.

She adds that after the Taliban takeover last year, the 18 women “looked to each other for reassurance. They shared how they couldn’t sleep, how they had dyed their clothes black, how they had soaked away the ink from pages of writing that was now a risk to possess as hard copy. Some took to the streets, others went into hiding; and six crossed borders and are now living in Germany, Italy, Iran, Sweden, Tajikistan, and the USA.”

That heightened awareness is evident in their storytelling.

“We smell onions frying in kitchens. We hear the jingle of an ice cream cart. We hold a purple handbag,” explains BBC journalist Lyse Doucet in the collection foreword: We sit on the ‘soft chocolate-covered seats’ of a luxury car which could only be afforded by someone else. These are the details we recognized in our own lives.”

But there are many details we can’t identify with and, like Doucet, I had to occasionally look away from the page.

“The Most Beautiful Lips in the World,” an exquisitely written piece by Elahe Hosseini, proved especially difficult to read. It is told from the perspective of an impoverished child who is coaxed into becoming a suicide bomber so she can reunite with her dead mother. The story draws from a real attack three years ago at a wedding hall in the Afghan capital.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))